We spoke with Musarrat Perveen, regional coordinator at Coordination of Action Research on AIDS and Mobility in Asia (CARAM Asia), who advocates at regional and global levels for policy reform of discriminatory practices that put migrant workers at risk of HIV and AIDS.

Continuing our coverage of AIDS 2024, the 25th International AIDS Conference, we spoke with Musarrat Perveen, regional coordinator at Coordination of Action Research on AIDS and Mobility in Asia (CARAM Asia), who advocates at regional and global levels for policy reform of discriminatory practices that put migrant workers at risk of HIV and AIDS, sexually transmittable infections (STIs), and other health conditions, as well prevent them from accessing health care services.

CARAM Asia, established in 1997, is a regional network of 42 migrant and migrant support organizations across 18 countries in Asia that focuses on coordinating research on AIDS and mobility. It helps to target the important challenges individuals face throughout the migration process and support community-based organizations in their efforts to both promote and protect migrant workers’ health rights, including sexual and reproductive health rights. These efforts aim to empower migrant communities by developing research, awareness publications, campaigns, and policy recommendations to protect migrant workers’ rights and address their health and welfare at national and regional levels.

The American Journal of Managed Care® (AJMC®): Can you explain the research you presented at the International AIDS Conference and what motivated you to undertake this study?

Perveen: Migration is a historical and global phenomenon driven by disparities in income and quality of life. Economic migration is driven by various factors. There are push factors that include inadequate labor standards, high unemployment rates, poverty, political instability, and weak economies, and there are pull factors such as higher wages, improved job prospects, and increased demand for labor. Migrant workers boost economic development by addressing workforce shortages in such sectors as construction, agriculture, services, and domestic work in receiving countries and by increasing the gross domestic product in sending countries through their remittances. For example, in 2015, the Philippines, Pakistan, and Bangladesh received $29.7 billion, $20.1 billion, and $15.8 billion, respectively.

Despite these contributions, migrant workers are still treated as commodities by the governments of sending and receiving countries, which neglect their human, labor, and health rights, resulting in their exploitation and abuse, and putting them at risk of HIV/AIDS, STIs, and other health conditions. Social, economic, and political factors further influence HIV risk among migrant workers, due to their separation from families, poor living conditions, and exploitative working conditions; they go abroad alone and experience cultural shocks, stigma, discrimination, and isolation. The resulting isolation and stress, combined with these policy restrictions, often leads to risky behaviors—migrant workers belong to sexually active and reproductive age groups—while seeking intimacy in a foreign country. Additionally, policies in receiving countries frequently prioritize short-term labor needs while overlooking the essential human needs and health rights of migrants. This results in limited access to crucial HIV prevention information and health care services, which, in turn, increases their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS, STIs, and other health conditions. Further restrictive in-migration policies dehumanize migrant workers by limiting their ability to bring spouses, get married, or become pregnant in receiving countries.

In 2005 and 2007, CARAM Asia conducted 2 regional research studies under the main title, “State of Health of Migrants.” The 2005 study focused on migrant workers’ access to health information and services in sending and receiving countries,2 and the regional research in 2007 focused on migrant workers’ mandatory health testing across various countries in Asia.3 These studies in Asia were groundbreaking, identifying numerous policy barriers and challenges experienced by migrant workers at every stage of the migration process, and highlighting that governments in the region generally failed to reform and implement policies protecting migrant workers’ health and rights despite international guidance on health provision for all. As a result, there has been limited policy and program work focusing on HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care for migrant workers.

The purpose of our research presented at AIDS 2024 was to gather current information and monitor the development of policies and programs concerning migrant workers’ health rights over the years. Our principal research objective was to evaluate the current status of health rights for migrants in 5 Asian sending countries: Cambodia, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. The research looked at how HIV- and AIDS-related policies and practices have changed over time and identified any positive changes in protecting migrants workers’ health rights, especially regarding HIV. It also identified remaining obstacles in this area. HIV is an important indicator because it is a sensitive health condition with wider social consequences of stigma and discrimination.

AJMC: What criteria guided your selection of Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka for this research?

Perveen: The selected countries for the study in South and Southeast Asia are some of the major migrant-sending countries. These countries are experiencing an increase in the working-age population entering the workforce while facing limited opportunities within their local job markets. Labor-exporting countries rely on policies that promote out-migration to relieve the pressure of underemployment. Simultaneously, exporting the surplus workforce provides considerable income to the countries’ coffers through foreign exchange generated by migrants’ remittances.

Many countries are willing to compromise their citizens’ rights by allowing or even helping them to move to countries that lack proper protections for migrants’ rights. Migration policies often prioritize securing macro benefits, leading them to neglect upholding migrants’ rights. Migrants’ health rights are quietly violated regularly, with the most dramatic incidents being labor exploitation, physical abuse, and trafficking.

We selected the 5 countries for our study for several reasons. First, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka were recognized as some of the major sending countries in Asia, with a significant number of migrant workers moving abroad in search of employment opportunities. These countries were important for studying changes in HIV/AIDS policies and obstacles in protecting migrant health rights, and they were previously included in CARAM Asia’s “State of Health of Migrants” reports.

Second, these countries had migrant workers who returned from various receiving countries, including the Middle East and the Gulf Cooperation Council countries of United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, and the Southeast Asian countries of Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore. These returning migrant workers brought valuable experiences and insights into the barriers they faced in accessing health services in different receiving countries, particularly concerning HIV/AIDS. Due to the lack of resources to conduct the study in the above-mentioned receiving countries, we analyzed the migrants’ self-reports and reviewed the sending countries’ policies.

Third, some of these sending countries were known for practicing strict policies that criminalized the transmission, disclosure, and nondisclosure of HIV. For example, in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, mandatory policies dictate HIV testing for employment abroad and disclosure of HIV-positive status to their families and prospective sexual partners. However, we belive that mandatory HIV testing violates human rights by infringing upon personal rights to privacy and confidentiality. No one should have the authority to demand an HIV test from any other individual, thus undermining their fundamental rights.

These policies say that informing partners and families about HIV is important to prevent its spread, but doing so can also cause stigma, discrimination, and treatment delays. Disclosing HIV status should be done in a way that reduces risks to individuals, such as through voluntary disclosure with informed consent and by providing psychosocial support to help them cope with partners’ and families’ reactions. Considering this illustration of criminalization policies, a comprehensive investigation was indispensable to examine the evolution of the reform of the aforementioned policies, and others, about safeguarding migrants’ rights, particularly their health rights concerning HIV/AIDS.

AJMC: What are some examples of discriminatory health practices and policies that migrants face, particularly concerning health screenings?

Perveen: First, mandatory health screening as a prerequisite for migrant workers entering destination countries is discriminatory and dehumanizing; it violates such basic rights as the right to employment and to access health services. Most receiving countries in Asia enforce strict health policies that discriminate against migrant workers based on their HIV status.

Before their work permit applications are accepted, migrant workers must undergo mandatory medical testing at the predeparture stage; their employment documents will only be processed if the test results show they are fit to work. Second, they have to undergo mandatory testing upon arrival in receiving countries, and if they test positive for conditions such as HIV, tuberculosis, or pregnancy, they are immediately subjected to criminalization, arrest, detention, and deportation by those governments—who also do not cover the cost of their return to the sending country. If they pass, they receive a 1-year work permit. This process repeats every year.

Failure to pass these tests results in arrest, detention, and deportation. Migrant workers filling unskilled or semiskilled jobs are specifically targeted for these examinations. Consequently, they are treated differently from locals and are excluded from the protection offered by existing laws and policies on HIV in both sending and receiving countries.

Second, HIV testing standards are often disregarded, including confidentiality and informed consent. Migrant workers often do not receive detailed information about the testing procedures or the conditions being tested for. They do not fully understand the consequences of a positive result and often feel pressured to sign documents without understanding them. Health officials frequently assume implicit consent or accept consent from recruiters, which is very problematic. The testing procedures can be invasive and may cause embarrassment, as they may require migrants to be completely unclothed or examined by health care providers of the opposite gender. Confidentiality is often breached, as test results are sent directly to recruiters, sometimes before the migrant is informed. Also, migrants are often not given their reports and are only told if they are eligible to work abroad or not, with little explanation if they are considered unsuitable.

Third, in some of the receiving countries, migrant workers are required to pay very high costs for public health care services compared with the locals, but their minimal salaries often place these costs far beyond their means. And if they try to access public health services, undocumented migrant workers who do not possess legal documents in receiving countries also face the risks of arrest, detention, and deportation. CARAM Asia advocates for universal health coverage for all regardless of their legal documentation status or if someone is living with HIV.

Fourth, there is a marked lack of awareness programs to prevent HIV among potential migrants who are in the process of leaving a country and there are no specific health services for returnee or deported migrant workers based on if they are living with HIV. Therefore, they may go back to their communities without even knowing the reason for deportation and transfer infections. There also are no data to identify these returnees, nor are there government programs to help locate and provide them with health services.

AJMC: Can you provide examples of health and migration policies reviewed in your study that discriminate against migrant workers?

Perveen: There are several examples of these policies:

- Bangladesh: The National Strategic Plan for HIV/AIDS (2011-2015) introduced strategies for combating HIV/AIDS among migrant workers, such as predeparture preparation; distribution of information, education, and communication materials; airport advertisements, and establishing voluntary counseling and testing centers. However, implementation of these strategies remains unclear, suggesting inconsistent access to health care services for migrant workers. This indicates that the policy inadequately addresses their health needs, particularly regarding HIV/AIDS.

- The Philippines: The Republic Act 8504 (1998) and other laws on HIV-related support and insurance have helped to improve HIV-related services. However, implementation and program sustainability remain challenges, especially in HIV testing and treatment for overseas Filipino workers, and there are persistent gaps in service coverage.

- Pakistan: The National AIDS Control Program (1986-1987)provided health access for migrant workers. However, treatment centers are more concentrated in major cities, making access to and awareness of these centers difficult for migrant workers who largely hail from rural areas.

- Cambodia: The National Plan of Action of the National Committee for Counter Trafficking (2014-2018) and National AIDS Authority’s 7-point Policy Directives do not specifically address migration health issues.

- Sri Lanka: Migrant workers receiving care throughGulf Approved Medical Centers Association–certified centers face mandatory HIV testing, but the centers do not ask for their consent for testing. If a migrant receives a positive results, they are immediately deported and blacklisted from employment in any Gulf country through a shared database.

The American Journal of Managed Care®(AJMC®): Why have migrants historically been excluded from national AIDS programs in the regions you studied?

Perveen: Migrants have been excluded from the national AIDS program in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka due to the governments’ lack of recognition of the workers’ vulnerability to HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in their national AIDS plans. Instead of being labeled as most at risk for contracting HIV, they are often only considered vulnerable populations. However, in the past, they also were not always considered vulnerable. Although these policies and perceptions have changed due to intense advocacy by CARAM Asia and other stakeholders in the region, the governments still are not recognizing the risk factors migrant workers face, highlighting the ongoing discriminatory treatment they face through the health policies of sending and receiving countries.

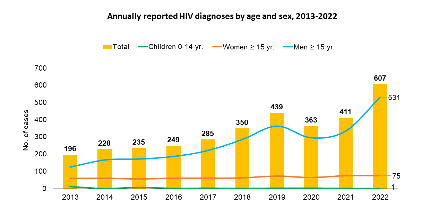

Annually Reported HIV diagnoses by Age and Sex

From 2013 to 2022 in Sri Lanka

For example, the countries studied categorize men who have sex with men, persons who inject drugs, sex workers and their clients, and Hijras as most at risk. Migrant workers are excluded from this classification despite data showing an annual increase in cases of HIV and a significant number of returnee migrants now living with HIV. In Sri Lanka, for example, 187 of 607 (30.8%) reported HIV cases in 2022 had a history of external migration, as shown in the figure.

AJMC: How are migrant workers more vulnerable to HIV vs nonmigrant populations, and what unique risk factors do they face in the receiving countries you studied?

Perveen: Migrant workers are more vulnerable to HIV compared with local nonmigrant populations because sending and receiving countries often treat migrant workers as commodities, neglecting their fundamental human, labor, and health rights. Their young ages when going abroad for employment also predisposes them to culture shock due to unfamiliar policies and conflicting cultural norms. This can lead to stress and anxiety, and neglect that make them more susceptible to rights violations, violence, abuse, and exploitation. Other unique risk factors for migrant workers in receiving countries include the following:

- Single-entry visas

- Prohibitions on marriage with locals

- Restrictions on bringing spouses

- Isolation in a foreign country

- Neglect of their human need of intimacy

The stress and anxiety also can result in behavioral changes that include unprotected sexual behavior, which raises the risk of contracting HIV. A lack of awareness about HIV prevention measures further increases their vulnerability to HIV and other sexual and reproductive health rights issues due to limited access to health information and services. Women also may experience sexual abuse and exploitation, particularly those working in the entertainment sector or as domestic workers, who often live in their employers’ private homes with no access to social support. In many cases, women are forced into the sex industry, which also increases their risk of contracting HIV and where they encounter many other health problems.

AJMC: What were the top health priorities identified by migrants in your focus group discussions, and what challenges did they highlight as barriers to equitable HIV/AIDS health care in the countries studied?

Perveen: Among the top health priorities identified by migrant workers during the research was HIV/AIDS, STIs, tuberculosis, and mental health. Challenges they highlighted as barriers to equitable HIV/AIDS health care include the following:

- Stigma and discrimination: People living with HIV/AIDS often face considerable stigma and discrimination from their families and society. This stigma leads many to conceal their HIV status, resulting in isolation and a lack of support.

- Financial burden: Migrant workers are required to undergo regular annual health checks, including tests for HIV and sexual health. These expenses are typically paid out of pocket by the workers, either directly or through salary deductions. This financial strain is particularly challenging for those with low incomes.

- Lack of health care coverage for undocumented migrants: In some receiving countries, registered migrants must undergo tests to qualify for health insurance coverage. However, undocumented migrants also often lack health care coverage, leaving them without access to essential medical services.

- Lack of access to embassy and consulate services: There are significant gaps in accessing embassy, consulate, and Philippine Overseas Labor Office services for overseas Filipino workers living with HIV. Reports from these migrant workers who were deported between 2012 and 2016 indicate they were quarantined without access to their embassies. Furthermore, receiving country health ministries or immigration offices are not obligated to notify embassies about workers’ health issues, resulting in a lack of connection to repatriation and reintegration services. Most embassies and consulates also lack funds and facilities to help migrant workers, and some even don’t even answer phone calls.

- Immediate deportation and blacklisting: Migrants who receive a positive result following an HIV test are often deported immediately and blacklisted from migrating to any Gulf country via the shared database. This deportation frequently occurs without providing information or referral services, leaving migrants unaware of their HIV status and its implications.

AJMC: Based on your research findings, what specific recommendations do you have for improving health policies for migrant workers in these countries?

Perveen: Sending and receiving countries should invest sufficient funds in HIV education for migrant workers to provide awareness about HIV/AIDS and STI prevention, and provide access to health services at all stages of the migration cycle. Also, most receiving countries should eliminate discrimination against labor migrants by reforming health policies that criminalize—via arrest, detention, and deportation—migrant workers based on HIV status, and ensure unrestricted access to health services for documented and undocumented migrant workers.

Governments of receiving countries also should ensure migrant workers get proper days off and, when possible, provide affordable, accessible, and healthy recreational activities as alternatives to risky behaviors for relaxation and holidays, including those that permit spouses. In addition, national AIDS strategies, strategic frameworks, and programs need to include migrants, migrant workers, and families and partners of migrants more prominently and address their specific needs with comprehensive services that are supported by appropriate levels of funding and interagency coordination.

It is also important to standardize laws and policies on HIV testing to ensure that any testing migrants must undergo adheres to internationally accepted standards that include informed consent, confidentiality, pre- and posttest counseling, and proper referral to treatment, care, and support services. The goal of testing also should become to prevent HIV infection, not to criminalize migrant workers.

Sending and receiving countries also should work to eliminate stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV and respect gender and sexual orientation among migrant workers, and receiving countries especially should provide employment access returning migrant workers.

AJMC: What final thoughts or messages would you like to share for future advocacy and policy change?

Perveen: Readers of CARAM Asia’s research might include important stakeholders in both receiving and sending countries, such as government agencies, politicians, policymakers, migrant nongovernmental organization, journalists, and other influential groups. We hope that our research on discriminatory policies and obstacles in protecting migrants’ health rights, along with our recommendations for improved health policies for migrants, reach this audience and they are able to highlight the necessity in addressing these ongoing issues. Through this research, we also strive for a deeper understanding of the impacts of discriminatory policies in receiving and sending countries on marginalized populations like migrant workers, in term of their health.

Prioritizing the voices and experiences of migrant workers in the fight against HIV is crucial, and we advocate for this through participatory action research and other means. Effective advocacy for the health rights of migrant workers requires active collaboration with various stakeholders, including migrant nongovernmental, civil society, community-based, and government organizations. This approach ensures that evidence-based knowledge is grounded in the lived realities of migrant workers.

For future advocacy and policy changes to be effective, it is essential to develop inclusive policies with active participation from migrant workers, enhance access to legal and health services, decriminalize and protect labor migrants, and foster ongoing collaboration among researchers, activists, health care professionals, and policymakers. This strategy underscores the transformative power of research-informed advocacy in creating equitable HIV/AIDS health care, particularly for vulnerable populations like migrant workers.

Reference

Perveen M. Lack of access to treatment and criminalization of labor migrants based on HIV-positive status: a review of HIV policy progression and migrant’s health rights in five origin countries in Asia. Presented at: AIDS 2024, July 22-26, 2024; Munich, Germany. Poster EPF198. https://aids2024.iasociety.org/cmVirtualPortal/_iasociety/aids2024/eposters#/PosterDetail/774