“In those days it just wasn’t considered something heterosexual people got,” says Bruning.

“It was a shock…In Tanzania there was no information about HIV. They only had one national radio station, and one newspaper newspaper and they were both in Swahili. There was very little information — HIV was perceived as a gay man’s thing that happened in San Francisco.

“It was very, very scary because there was absolutely no infrastructure or support. I was told I had three years to live and to sleep well, eat well, and don’t have sex.”

Bruning said the ensuing period was “surreal”.

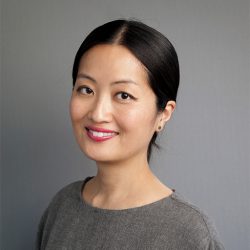

Jane Bruning, national coordinator for Positive Women, says New Zealand is at a crossroads when it comes to how we approach HIV.

She relocated to New Zealand so her family could take care of her son when she was gone.

For years she waited to die.

Then, antiretroviral treatment drastically changed the lives of people living with HIV for the better.

With daily medication Bruning realised she would live to meet her grandchildren after all.

Nonetheless, everything was different.

“I don’t know that it’s been a normal life and I’m not sure I would say it’s been 100 per cent healthy because of the side effects from the medication. I knew I wasn’t going to die, but I wasn’t quite sure how to live.”

Bruning, now 59, is one of a small percentage of heterosexual women in New Zealand living with HIV.

It hasn’t been an easy road.

From a medical perspective she is healthy albeit some side effects from her daily medication including peripheral neuropathy, lipoatrophy and lipodystrophy, however, life hasn’t been the same since.

She hasn’t had a partner in 20 years, which is a personal choice. “I thought I was coming home to die so I didn’t see any point in getting into a relationship”.

As the national coordinator of Positive Women, a support agency for women living with HIV and their families, she has come across cases of people being treated like lepers despite medication reducing their risk of transmission.

Earlier this month prosecutors at the Auckland District Court accused Mikio Filitonga of burying his head in the sand when it came to his own HIV diagnosis.

He was found guilty of causing grievous bodily harm to his former partner by infecting him with HIV, and of committing a criminal nuisance by having unprotected sex with him knowing he had HIV and not disclosing it.

Evidence heard at trial established Filitonga was evasive with medical authorities, shunned treatment, and didn’t tell his partner of his diagnosis.

He is one of around a dozen people who have been charged with offences relating to the infliction of HIV since Kenyan musician Peter Mwai became the first person to be prosecuted in 1994.

Unlike some countries or US states where law has been specially crafted for the offence, prosecutors in New Zealand utilise existing legislation to prosecute those whose recklessness leads to injury.

But given people living with HIV can have long, healthy lives—can injury be proven?

Filitonga’s defence lawyer Ross Burns applied to have the charges formally dismissed by the Judge, arguing that the definition of grievous bodily harm hadn’t been met because the complainant was taking medication that made him asymptomatic—technically injury free.

Judge Mary-Beth Sharp rejected the application, saying HIV was an “indisputably serious” illness.

“It is incurable, chronic, and can cause death. With respect, that says it all,” she says.

After the trial the New Zealand Aids Foundation criticised the prosecution, saying court action should only be taken where malicious intent to infect others is established.

The Sunday Star-Times asked: Should people still be prosecuted for inflicting a manageable illness when many others, such as measles, can cause the same damage but aren’t pursued through the courts.

“I do think HIV is a big deal. I wouldn’t want anyone to contract it. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody,” says Bruning.

“In saying that, with the medication making viral loads undetectable, I think we’re coming to a real crossroads. Do you need to wear condoms? Do you need to disclose your status? Clinically, there is no reason why someone should have to wear a condom or disclose. Morally, you have a whole different story.”

Long time infectious diseases physician Dr Graham Mills says it’s an “interesting paradox”, and its silly to compare HIV to measles or other highly infectious diseases that don’t become the subject of criminal prosecutions.

Society’s continued efforts to reduce transmission rates, including the prosecution of reckless persons who pass it on to others, are at odds with the fact medical advances can render HIV virtually undetectable, he says.

Mills works with a 190 HIV patients under the Waikato District Health Board umbrella and gave expert evidence in the Filitonga trial.

He wouldn’t comment on the case but admitted that he became fascinated with specialising in infectious diseases during his time as a medical student at Otago University when a mysterious illness known only as GRID (gay related immuno deficiency which later became known as HIV) became known in the United States.

Since then he has seen patients die, but many also live normal lives.

“Ask yourself, why do I want to reduce HIV? One, because it forces people to be on medication and treatment for the rest of their life.

“Two, it’s expensive. It costs about $10,000 a year for pharmaceutical and out patient costs. Most people don’t pay that much in tax per year.

“Three, it’s an ongoing epidemic, and there are people that lose in any epidemic. The people that lose out are the people that have barriers to health care.

“We’re not criminalising HIV. We never have. We have existing laws to hold people to account because someone has complained, because they believe they have come to serious harm, and therefore we’re giving them the framework with which to lay a complaint.”

Auckland University law professor Julia Tolmie says case law evolved at a time when HIV was “an inevitable death sentence”.

“That has certainly shifted now. Nonetheless the illness would still fall within the definition of grievous bodily harm, which just means ‘really seriously hurt’ or ‘really serious bodily injury’. Something can be ‘bodily injury’ even if treatment is available to cure or manage it,” she says.

The “real issue” for the courts is whether a person’s HIV positive status has been disclosed to consenting partners.

“I think there is an argument that you could apply the same legal principles to, for example, herpes, which is arguably grievous bodily harm, but may not be considered to be dangerous to life.

“I do not know about the infection process for measles but I imagine one of the difficult issues there would be establishing that a person purposefully risked infecting others—people may well be contagious before they know that they have the illness.

“Of course, there is also the need to have a complainant before criminal charges will be laid. People may well not think of informing the police where someone has deliberately risked infecting them with measles or other illnesses.”

Susan – not her real name – disagrees. Her former partner Darryl Kilpatrick was jailed briefly after he had unprotected sex with her without disclosing his HIV status.

She underwent years of testing before receiving confirmation she hadn’t been infected, but she developed post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and attempted suicide.

Susan firmly believes people who inflict HIV on others should be charged with a sexual offence, describing her own experience as akin to being raped.

“The effects are identical to rape and sexual violation. The breach of trust, the health issues—it’s an absolute threat to life and future sexual relationships”.

“It’s been a long, lonely journey and I have to say it’s never ending. It’s been very hard,” says Susan.

She said people “minimised and rationalised” her situation because she hadn’t been infected, and she became frustrated with the lack of support.

“I rang the Wellington sex abuse helpline and the woman on the phone said to me, ‘I don’t know how to help you’. I just screamed at her saying, ‘can’t you see I’ve been sexually violated?'”

Susan later successfully pursued ACC through the High Court in order to get payments for her PTSD, after the agency initially said it didn’t recognise her injury.

The NZAF said prosecutions had the “significant potential” to undermine previous successes in breaking down stigma and discrimination, and reducing HIV incidence rates.

Director Jason Myers said it weakened public health messages of shared responsibility for sexual health and promoted the perception that they are “potential criminals or a threat to innocent’ people”.

“For these reasons, the application of criminal law to the transmission of HIV should be kept for those very few cases in which a person who knows their HIV status has not disclosed this to a sexual partner and acted with the express intent to transmit the virus. Invoking criminal laws in cases of adult private consensual sexual activity is disproportionate and counterproductive to enhancing public health,” said Myers.

According to Bruning there is a strong difference between keeping personal information secret knowing it won’t affect anyone else, and being reckless or deliberate.

“To me, burying your head in the sand is not is not useful, although I understand how stigma can affect people to an extent they are in denial, but that’s very different to someone who injects their blood (in 2009 an HIV positive man deliberately injected his sleeping partner with his blood to deliberately infect her so they could have sex) into someone else,” said Bruning.

Published in Stuff on April 2, 2017