Held Harmless

By Heather Boerner, From TheBody

Science Guided Switzerland Away From Prosecuting People Living With HIV for Theoretically Exposing Their Partners To The Virus. Could It Happen Here, Too?

In November 2008, a 34-year-old African man was sitting in a jail cell in Geneva, Switzerland. We don’t know his name — only that court documents called him Mr. S. We don’t know which country he immigrated from. He could have been anyone. All we know is that, to the state, he was a criminal.

He was serving 18 months for having condomless sex without disclosing his HIV status. He had argued that it didn’t matter because he had an undetectable viral load and couldn’t transmit the virus. But the lower Swiss court in 2008 wasn’t convinced. Under Article 231 of the Swiss Penal Code and under Article 122, nondisclosure was considered an attempt to engender grievous bodily harm, and he was solely responsible for curtailing the spread of HIV.

One month later, the appeals chamber of the Geneva Court of Justice held him harmless.

What changed in that month was that the long-term work of activists and people living with HIV converged with both good luck and the emergence of the science of viral load and transmissibility. It would take another several years after Mr. S’s acquittal for the law to formally change. But in 2016, concerted work would change Swiss law forever, such that no one with an undetectable viral load has since been convicted of attempting to transmit HIV without also having a malicious intent.

“One should not,” Geneva’s deputy public prosecutor Yves Bertossa told the newspaper Le Temps at the time of the 30-something year-old man’s exoneration, “convict people for hypothetical risk.”

As American state legislatures continue to grapple with how to modernize decades-old laws that criminalize non-disclosure of HIV status and “attempts” to transmit the virus, and as the Swiss statement — the first time U=U entered the world — reaches its 10-year anniversary, we look back on one model of how to do this work. And we start with a woman who has been on both sides of the issue.

An HIV-Negative Woman Turned Positive

Michèle Meyer has a shock of flaming red hair and a temperament that does not suffer fools gladly. And she definitely considered Switzerland’s HIV criminalization laws foolish — even before she herself was living with HIV.

Meyer learned about the laws in the early 1990s, when she and her partner wanted to have a baby. The fact that he was living with HIV and she wasn’t didn’t deter her. She’d decided she was willing to take a risk.

So she asked a doctor what would happen if they just had condomless sex.

He told her, she said, that among the many possible outcomes was that he could be arrested for endangering her and the public’s health.

“It’s crazy,” she said in heavily accented English. “We were two adult people who decided together and there was no violence, no dependency. We were on the same level to decide — so lawmakers have nothing to look for in our bedroom.”

The news that her partner could be prosecuted for doing exactly what she’d asked him to do scared her off from trying to get any more information about how to lower her risk of acquiring HIV during conception. Privately, the couple had condomless sex. And Meyer did get pregnant — the fulfillment of what she called a lifelong “child wish.”

Then, in February 1994, Meyer lost her pregnancy. Ten days after that, she tested positive for HIV.

Suddenly, she said she had to process two things: One was what she described as the cruelty of medical providers, who she said told her, “It’s good that your child is dead, because you are HIV positive.”

The other was her new reality on the other side of the HIV criminalization line. As she put it: “And then to know that I could be sentenced?”

It made her extra careful with later sexual partners. Twice, she said, she kicked men out of bed and out of her house, naked and throwing their clothes after them, for taking off a condom during sex without telling her.

“I was not going to risk going to jail for them,” she said. “And they decided, even without talking to me, to take [the condom] off because they were having fun with the risk? This made me crazy.”

She also took another measure. She said she told partners (women and men): “No one comes into my house without a test — because it’s not my intent to be held guilty for someone else’s infection.”

These were stop-gap measures, though. It would be much easier, she said, if the law weren’t there at all. So when, in 1999, her doctor informed her that she was on stable treatment and couldn’t pass on the virus, she did two things: She tried for and conceived two children — girls now aged 16 and 15, both born without HIV — and she began fighting in earnest for a change to the law.

As a feminist and someone who spent her teen years protesting nuclear power, it was natural for her. First she agitated for her local AIDS service organization to start a support group for women newly diagnosed with HIV. Then she put herself forth as a public figure, someone willing to speak openly about her diagnosis — a rare event at the time.

Most World AIDS Days, she said, you could find her face and her name in the papers, where, she said, she’d “always tell them I have sex without condoms.”

“It’s illegal,” she said she’d tell them. “But if I can’t infect my partner, it’s a crazy law.”

She even tried to find the most conservative cantons — the Swiss version of states — and try to get them to arrest her for exposing her partner to HIV. She’d plan weekend getaways and get amorous with her partner.

“I would later go to the police and tell them, ‘I had sex without a condom,'” she said. “I was waiting for someone to charge me. But we didn’t find one who wanted to bring charges against me. I was too open with the idea.”

Eventually, she found her way onto the Swiss National HIV/AIDS Commission, (abbreviated as EKAF in German), a national group of policy makers, bureaucrats, scientists, doctors and activists, where she said it was other people’s job to be diplomatic. Her life and freedom were at stake.

“As an activist, you can’t be diplomatic,” she said. “Criminalization will not come to an end that way. I’m radically against any criminalization, even if an infection is happening, even if there is a real risk. It’s not OK.”

A Social Worker Turned Lawyer

In the early 2000s, around the same time that Meyer was raising her daughters, a man she had never met was spending time with people receiving treatment for HIV-related conditions elsewhere in the country. And he found himself, he said, confronted with the reality of how HIV stigma alters the trajectory of a life.

People regularly told friends that they were sick with anything but HIV, Kurt Pärli, a wiry man with a thick head of hair, told TheBodyPRO. Cancer was a popular cover story.

“Having the diagnosis of HIV/AIDS led to a social death long before the physical death,” he said, adding that it was clear to him that the criminal laws and the epidemiology law were an extension of this stigma.

At the time, he was a social worker. But when he went to law school, he wondered how to disentangle the legal system from the health of people with HIV.

The first thing that would have to change, he said, was the general understanding of public health, one common in much of the world, including the U.S.: It assumed that criminal prosecution could curtail the spread of a disease. The country’s epidemiology law had been enacted in the 1940s to hold female sex workers liable for transmitting syphilis to “innocent clients,” as public health official Luciano Ruggia told TheBodyPRO.

“The article [231] remained dormant until the late 1980s, when some judges started to use it in HIV cases,” Ruggia said.

In practice, though, Article 231 wasn’t used just to prosecute actual transmission. It was also used to prosecute hypothetical risk — that is, potentially exposing someone to HIV; or, simply, having sex without a condom and/or without disclosure. In July 2008, Switzerland’s Federal Supreme Court in Lausanne even ruled that people could be convicted under the law if they didn’t know they were living with HIV at the time of sex. Another court ruling found that if you have symptoms that might indicate you have HIV, or if you have good reason to believe that someone you had sex with has HIV, you either had to disclose that suspicion or practice safer sex — failing either of which, you risked prosecution.

At a time when people wouldn’t admit to having HIV to anyone, Pärli watched people shy away from HIV testing to avoid being held liable under the law.

“From the perspective of the criminal law, it’s not a question of the two individuals, of if they are willing to take the risk,” he said. “That’s the old way of how to deal with public health. … It wasn’t effective.”

But there was a new way, a legally non-binding public health approach enacted in Swiss AIDS policy in the 1990s — one that held that every person in a relationship is responsible for their behavior and responsible for curtailing the spread of diseases. That approach said that it’s up to each partner to care for themselves, and the more they were able to do that, the better it was for everyone. HIV testing is part of that — but you don’t test if you are afraid of going to jail for having sex, he said.

And you don’t take measures to prevent transmission during conception if you don’t know what they are, Meyer said.

“I will not say that the law is guilty for my infection; that was my responsibility,” she said. “But I see there is a point that I was a threat [to my partner’s freedom] and didn’t seek enough information, just because of the law.”

A Public Policy Approach

Changing Swiss HIV criminalization laws would not be easy. For one thing, the laws used to prosecute people living with HIV are general and apply to any form of assault or transmission of human disease. For another, the Swiss don’t follow the legal concept of binding precedent, said Sascha Moore Boffi, a jurist with the Swiss HIV organization Groupe sida Genève. So what happens in Geneva doesn’t necessarily change a later decision in Zurich or Obwalden. Each case, he said, is decided on an individual basis.

For another thing, there’s no national database of every decision made in every canton. To find out what the courts were doing, Pärli called all 23 of the cantonal courts to get their information.

The results were, perhaps, not a complete picture. Only 62 of 94 courts responded.

But what they told Pärli was significant: Cases against people living with HIV had been going up across the country, from two cases before 1994 to nine cases between 2005 and 2009, with 39 people prosecuted since 1990. Twenty six of those were convicted. And half of those were despite the fact that no one acquired HIV.

Most cases involved new couples having sex without one partner knowing the other’s HIV status or where the person living with HIV had lied about their status. Three people were prosecuted and convicted for having consensual sexual contact with a partner who knew their status and consented to taking the risk.

People who were convicted spent an average of 18 months to two years behind bars, but one case resulted in a three year sentence — that one included a conviction for coercion and assault, according to Pärli’s report.

One person was convicted only of having presented a risk to public health — meaning he wasn’t convicted of having caused any actual harm — and the court ordered a suspended sentence and an obligation not only to disclose HIV status to partners, but also to register every sexual contact with the state.

This put Switzerland’s HIV criminalization rates amongst the highest in Europe, said Boffi.

The Behind-the-Scenes Guy

Luciano Ruggia would prefer you not know his name. He’s not shy — in fact, with his frank manner and expressive hand motions, he’d be more aptly described as gregarious. But he prefers to do his work out of the spotlight.

“That’s where I can achieve more,” he said. “You really have to keep a low profile if you’re inside an administration.”

That’s where Ruggia was in 2006, as EKAF’s scientific secretary, a position within the Federal Office of Public Health. It was part of his job, he said, to present the commission with issues it might tackle. To that end, he read reports from Pärli and attorney Fridolin Beglinger, and discrimination reports by Boffi’s group and others, and listened to the opinions of activists like EKAF member David Haerry.

That’s how he learned about the impact of Article 231, and the epidemiology law, Article 122, on people living with HIV. Ruggia said he considered the law itself ethically wrong and functionally ineffective, but he knew just repealing a criminal statute was a non-starter in a parliament he said was composed primarily of lawyers.

“It’s very bad press to raise” repeal of any criminal statute, he said. “If you look, in every country, the criminal code book only gets bigger.”

And EKAF could recommend a change, he said, but that’s where its power ended.

They needed to find a way to link the law on epidemiology to the criminal code. And it was a stretch, he said.

So nearly two years before the Swiss statement codified U=U’s forbearer into Swiss medical practice, Ruggia did something he wasn’t sure would work. The administration was considering updating the entire epidemiology law, to bring it current from its 1970s drafting, and to address new epidemics, including SARS and H1N1.

What if he could slip into this update a change to the language in Article 231, one that stated people could only be prosecuted if there was actual transmission and if there was malicious intent on the part of the person living with HIV? And what if he could convince others in the administration that this was, after all, a small, technical change not worthy of note?

So he wrote up the amendment and slipped it into the end of the draft bill circulating around the capitol. It went unnoticed in its first year. It seemed to be considered just another little amendment necessary to bring other laws in compliance with the new rules, Ruggia said.

“It was seemingly a little bit harmless,” Ruggia said with a subtle shrug and a twist of the wrist meant to dismiss it.

By December 2007, the change made it into the version of the bill that was released for public comment.

Ruggia was relieved.

And then he took action to try to ensure it stay in there: He drafted up a letter of support for the amendment from EKAF. He called Boffi and his counterparts in the French- and Italian-speaking parts of the country. He asked them to write letters of support for the change, to show its broad support.

Their letters of support were added to the public record. By the time the comment period ended six months later, Ruggia’s amendment went untouched.

“I remember saying, ‘Let’s try this. This could work,'” Ruggia said.

The Doctor Turned Activist

Then something else that Ruggia had been working on behind the scenes came out publicly: a statement in the Bulletin of Swiss Medicine saying that people who have had a suppressed viral load for at least six months, who have no other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and who are monogamous need not use condoms because they can’t transmit the virus.

This became known as the Swiss statement, a scientific policy intended to allow Swiss providers to talk openly with their patients about their options for conception and other activities, but which resonated around the scientific world, where it was largely lambasted.

For Dr. Pietro Vernazza, M.D., the lead author of the statement, it wasn’t purely scientific. He said he was thinking of HIV modernization while he, Bernard Hirschel, Enos Bernasconi and Markus Flepp drafted the statement, too.

But Vernazza hadn’t heard about it from his own patients in his clinic at a provincial St. Gallen, Switzerland, hospital. There, Vernazza was working with people living with HIV who were forgoing having a family with their HIV-negative partners out of fear of transmitting the virus — a fear, he said, that was not backed up by any case reports of people on effective treatment transmitting HIV. This supported his own clinical experience, and the experience of the Swiss HIV cohort at large.

By 2007, Vernazza had been on the EKAF for eight years and was now serving as its chair. He had the power, but it took Pärli’s advocacy for Vernazza to understand the effect of the law on his patients.

“[Pärli taught us] that not only did we have the highest number of convictions within Europe but also that these convictions were not justified,” Vernazza said. And just like the pointless delay or abdication of children, HIV criminalization laws were pointless, too, he said.

“To me, this is a situation where you can’t just say, ‘OK I’m not involved in politics,'” Vernazza said. “It motivated me to do something against it if I could. And I was in a position with this commission that I was influential enough to use this influence [for my patients].”

He paused and added, “I would consider it my duty in such a commission to fight against the incorrect application of the law.”

Indeed, the conclusion of the Swiss statement makes this specific: “Courts will have to consider [this statement] when assessing the reprehensible nature of HIV infection. From the point of view of the [EKAF], unprotected sexual contact between an HIV-positive person with no other STIs and on effective [antiretroviral treatment], and an HIV-negative person does not meet the criteria for an attempt to spread an illness. It is not dangerous in the sense of Art. 231 of the Swiss Penal Code, nor to those of an attempted serious bodily injury according to Art. 122.”

An Opening for Change

By late 2008, the Swiss statement was beginning to find its way into criminal proceedings — and not by accident. Pärli said there was a concerted effort to translate the statement from its scientific source to the legal world.

“The legal world is sometimes like an autonomous planetary system or something,” Pärli said. “There was a need to bring this information to lawyers and to judges and to the courts. But finally, it had an effect.”

Indeed, the Swiss statement came out at the beginning of 2008. By the end of that year, one of the statement’s primary authors, Hirschel, had testified that Mr. S couldn’t have transmitted the virus because his viral load had been undetectable since at least the beginning of 2008. This directly contradicted the statement of a medical examiner during the first trial, that “a risk of contamination remained in a context of undetectable viremia.”

Prosecutor Bertossa dropped charges against Mr. S during the appeal of his conviction. That was followed the next year by another acquittal based on the same grounds, according to a study presented at the European AIDS Conference in 2013.

Collectively, these decisions became known as the Geneva judgments, and they were just as much of a watershed in Switzerland as the Swiss statement.

But for Ruggia, who was still watching his amendment move at a glacial pace through the Swiss legislative process, neither the Swiss statement nor the Geneva judgments were enough.

“Article 231 was still there,” he said. “Even in the case of a judgment that goes up to the federal court, there was no guarantee that the Geneva judgments would be heeded. Usually judges are not as open and progressive.”

Again, lack of the legal concept of binding precedent meant that judges in other cantons were free to make their own judgments.

Arguing Against “Virulent” Laws

So when Pärli’s report came out the following year, in 2009, it didn’t just describe the problem; it also argued that, for many reasons, the law needed to change.

For one thing, it argued that even without the Swiss statement, consent to taking a risk ought to be a defense against prosecution under Article 231 — and protection from HIV is both party’s responsibility. Think of it as an “it takes two to tango” doctrine, a doctrine that conformed with the new Swiss AIDS policy approach to public health.

If both people are culpable, the English-language fact-sheet stated, then it stands to reason that either both should be prosecuted, or neither should.

“If one does not wish to draw this conclusion,” it states, “a restriction or reversal of the application of Article 231 of the Swiss Penal Code would be worth investigating de lege ferenda [in future law].”

But the Swiss statement does exist, he went on to write, making the burden of consent and disclosure “even more virulent.”

“Given that punishment on the grounds of an attempted crime always requires that the accused acts willfully, in cases of unprotected sexual intercourse where the HIV-infected person complies with [the Swiss statement], conviction on the grounds of attempted bodily harm is ruled out,” the fact sheet states.

These issues, the report said, “shows the necessity to review Swiss Supreme Court practice.”

But getting rid of the disclosure and consent rule is politically unfeasible, Boffi said. This is because Swiss law applies the same standards of informed consent to HIV disclosure that govern informed consent in the law in general, such as before surgery. So “it’s difficult to find a way to mitigate that without weakening other forms of informed consent that we want to keep,” Boffi said.

There is one way to avoid disclosure, though: Swiss law holds that practicing accepted rules of safer sex is a defense against prosecution.

“As far as [the Article 231] was concerned, our Supreme Court decided that when protection was used, no disclosure was necessary,” said Boffi. “It didn’t say a condom needed to be used, only that if the person abided by the rules of safer sex, that person was free of the obligation to disclose.”

So Boffi and others saw an opening there: If treatment was considered protective, it could influence the law and legislators.

“Our argument was that it’s very simple: It’s very important to take the HIV test, because now there’s treatment — testing is an opportunity for treatment — so every hurdle in the way of letting them test is not cost effective for public health,” Pärli said. “As long as the criminal law was persecuting individuals who are HIV positive and took some risks, there was no incentive to take the test — especially for those who are acting not all the time in safe ways. It’s very important to reach those people, and the fact that they were afraid after being tested that they would be criminalized, that was an important point.”

And with what the Swiss statement revealed about how effective treatment prevents people who live with HIV from transmitting the virus, even if they are not using condoms, overcoming that barrier to testing and treatment is even more important.

“The more sick one is, the more risk they have to transmit the virus,” Päril added. So the law just didn’t make sense. “One of the important lessons we learned was that it’s important to act with patients and not against them.”

A Switch and a Scramble

But just as the introduction of the epidemiology law overhaul bill went to parliament in 2010, everything changed again.

“Here I was, I was very happy, I was not screaming. I was keeping a low profile because the article [amendment] was there and nice and fine,” Ruggia said, his words speeding up and becoming more clipped. “And then two days before [it was introduced to Parliament] … they changed the article.”

It turned out that someone from the Department of Justice, at the last minute, had noticed the article and pressured officials to remove it from the bill. They did, and Ruggia’s bosses raised no objection.

Suddenly, Ruggia went from hopeful to both furious and scared: anger at his bosses for not fighting the change, he said, and anger that the change went against the expressed comments of organizations that responded to the proposal (comments he had encouraged); and fear because “the odds change in parliament. You don’t know what’s going to happen.”

“I told myself, we cannot leave it like this,” he said. “Working with the press is always a risk. Working with politicians is always a risk. If you want to achieve something, you have to try to take some risks.”

So despite the fact that he was having to do exactly what he didn’t want to do, and despite the fact that he wasn’t sure he even could do what needed to be done, Ruggia started talking to connections in parliament to try to undo the change.

As in the U.S., the process of bill approval is long, and starts in a committee — in this case, in the national council commission on health of the lower house of Switzerland’s parliament. There would be a hearing on the bill.

Ruggia decided the commission needed to be at that hearing, he said. But they could not just invite themselves.

“I needed someone from the committee to invite us,” he said. “I knew someone in the committee and I asked him, ‘You should get me an invitation.'”

First hurdle cleared: The invitation was issued.

But Ruggia didn’t want to be the one up there talking publicly. “I prefer to get people better than me to speak in public,” he said.

He managed to line up a few lawyers and policy analysts. Pärli was out of the country, so he asked other attorneys to speak on the law and public health.

That’s the next hurdle sorted, he thought.

Then he primed the pump: As the hearing approached in 2011, he asked Vernazza to speak to a newspaper reporter about the Swiss statement and the scientific argument for changing the law. They needed, he said, “an article in the press supporting the change.”

Next, he studied the committee members again and tried to figure out who on the committee would be his biggest challenges. Once again, Ruggia’s goal was to draw as little attention to the change as possible, for fear of attracting vocal opposition. So he looked at the committee members in the far right party, and discovered that someone in Ruggia’s network knew one of the conservative committee members pretty well.

It was a stroke of luck, something Ruggia could never have expected, he said. So that member of Ruggia’s network met privately with the committee member and, in Ruggia’s words, “had a discussion before the hearing.” Ruggia said this wasn’t to lobby, but to educate. He declined to name the member of Parliament or the member of his network who met.

And all along organizations like UNAIDS and others were issuing reports and studying HIV criminalization laws around the world, to keep a spotlight on the issue.

Then came October and the day of the hearing. The article came out. Experts testified. The Swiss statement was presented into evidence as a statement from an official group of the parliament.

And the far right party members, he said, stayed mum.

“We didn’t get any opposition,” he said.

The revised amendment still required people to inform their partners of their HIV status, regardless of viral load. And while it made penalties more severe for people who purposefully transmitted HIV, it still allowed courts to punish people who passed on the virus unintentionally, according to a 2011 report from the newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

It wasn’t the victory that Ruggia wanted. But, he said, it was better than leaving the article as it was, with no changes at all.

Change From the Left

As the bill moved from committee to the Parliament at large, it was a touchy time, said Pärli.

On the one hand, parliament was overhauling its whole epidemiology law — not just its approach to HIV. And most of the discussion was about whether and what vaccines should be required for children to attend school.

“This was an advantage,” said Pärli, “because there was not a huge debate about this particular issue. [HIV] wasn’t the focus.”

On the other hand, they feared the day that HIV did become the focus, and what would happen.

“We were a bit afraid — what will happen when one day the Parliament is debating the issue of HIV/AIDS and what protections should be enacted into law, and then to argue it’s against the public health if the transmission of HIV is criminalized,” said Pärli. “This is quite crucial — how to convince ordinary members of parliament who are not specialists in public health.”

And how to do it, he said, in a rational way when, as it comes to HIV, “the questions are not discussed in a rational manner.”

So Pärli, Ruggia and their networks tried to keep the issue out of the limelight, avoiding reporters, and praying that a big splashy case of someone intentionally transmitting HIV wouldn’t take over the news and the consciousness of members of Parliament. When occasionally it did bubble to the surface in a positive way, Ruggia said he would send the article to his contacts in Parliament.

“You don’t just stop,” he said. “You send an email here or there.”

Meanwhile, Meyer was getting more and more irritated with the law as it was amended.

“I was really upset with them [on EKAF],” she said. “It wasn’t just about the law for me. My big hope was to change the stigma, end the stigma.”

She was convinced that EKAF, Ruggia and the rest of them had it backward: prevent discrimination, and then everything will get easier. For her, it wasn’t really about the science.

“Because then it’s just a virus, and you can have information and testing and treatment,” she said.

So she kept pushing, talking to her contacts in Parliament as Ruggia talked to his, advocating for a better change to the law.

“I was so glad there was one man in Parliament who really understood what was needed,” she said.

That man was Alec von Graffenried, representative of Switzerland’s Berne region at the lower chamber of parliament, known as The National Council, at the time of the law’s passage. He was a member of the Green Party and on the National Council’s Legal Affairs Committee. Meyer said she’d spoken with him in the past, though she didn’t speak directly with him about this bill. Meyer also said she knew people who knew him. And she was constantly talking to them about how wrong the law was to be there at all.

Similarly, Ruggia said he hadn’t approached von Graffenried, either. But somehow, von Graffenried found articles on the law. He told the UN Development Programme and the Inter-Parliamentary Union in a report issued later, that he simply felt it was a good opportunity to bring the law in line with the science of HIV.

So in 2013, when the bill finally made it to the floor of The National Council, von Graffenried presented a last-minute amendment that said that the law should only prosecute the rare case where someone with HIV maliciously spreads the virus — rather than people who, he said, were engaged in “normal sexual relationships.”

It was a proposal that shocked Meyer, Ruggia — everyone.

“I was not expecting that at all,” Ruggia said. And even more surprising, he said, von Graffenried’s proposal was a well formulated one.

“He was taking the law in the draft and saying, ‘We can formulate this better,'” he said. “I think he’s the only one who noticed Article 231 in the bill at all.”

For his part, von Graffenried has said the new language just made more sense.

“We can still prosecute for malicious, intentional transmission of HIV,” he’s quoted as saying in the UN report. “But I expect those cases will be very rare. What has changed is that now people living with HIV — which these days is a manageable condition — will be able to go about their private relations without the interference of the law.”

All the evidence, he said, suggests that “this is a better approach for public health.”

His amendment passed 116 to 40.

It would take another three years for the law to go into effect: the public still had to vote on the new epidemics law, which included the amended Article 231. Anti-vaccine advocates put a proposition on the ballot to challenge the vote. , based on a proposition put forward by what Ruggia described as an anti-vaccine. The vote failed.

The report concludes that, as a member of the Justice Committee, von Graffenried was well placed to make this argument. This should be a lesson to advocates, the report states.

“Campaigners and parliamentarians need to ensure that all the relevant departments are lobbied when working on such changes,” the report states.

For Boffi, the result shows that long-term advocacy is worth it. “What can be said is that the years and years of vocal opposition and lobbying and advocacy and information — and especially information based on concrete evidence — did have an effect in the end. We did have the majority of parliament say this wasn’t an issue. It does confirm that advocacy, even though in the short term it doesn’t succeed, in the long term it can create the necessary conditions that lay the groundwork and then benefit from the fruits.

Still, there was more than a little luck involved.

“It could have gone the other way,” he said. “We were very fortunate to have that one member of parliament. … I don’t believe he ever did anything related [to] HIV before that.”

The Living Legacy of Stigma

Groupe sida Genève’s Boffi joined the organization long after the groundwork had been laid for Article 231’s modernization. He came on in 2010, after Ruggia’s draft amendment to the law, after the Swiss statement, after the Geneva judgments.

He remembers clearly his colleagues coming home from the International AIDS Society conference in Vienna that year, and how so much of the discussion was on the Swiss statement and how dangerous it might be.

Today, a decade later, Boffi said that the impact of both the law change and the Swiss statement has been immense.

“The relief [among people living with HIV] was palpable,” he said. “People were saying, ‘Oh this is wonderful. I can seriously consider having sex again, and not be panicked or anguished that I’m putting my partner at risk.'”

But even in Switzerland, the stigma isn’t gone. There’s less structural stigma there, he said. But it’s still around. He spends a chunk of his time working with migrants being deported to countries where they won’t have access to their HIV treatments.

And people are still being prosecuted for HIV transmission, he said. Again, there’s no central database for cases — and in Switzerland, he said people often don’t seek out organizations like Groupe sida Genève when they are arrested, as people do in the U.S. Anecdotal cases reveal that people who are not on treatment are still being unsuccessfully prosecuted, he said.

“This aspect has been forgotten,” he said. “We haven’t got a solution for them as far as criminalization is concerned. They shouldn’t be prosecuted either.”

And even if someone is on treatment, it doesn’t always protect people. Since the update of the epidemiology law, he said he’s watched the HIV advocacy community somewhat disband. They are not still organizing around the issue.

But the Swiss statement, as much of a watershed as it is, is not enough to end HIV criminalization, Boffi said.

“We have prosecutors now who are starting to try to have judgments where the simple fact of transmission is considered proof of mal-intent,” he said. “For the time being, this hasn’t gone further than the lower courts and fortunately there’s been no conviction in the lower courts yet. But it is a risk, and it has to do with the fact that, rather than learn from the campaign that long-term advocacy is necessary, we did the exact opposite.”

Today, he said, U=U is a new concept in Switzerland.

“It’s strange,” he said. “We forgot our own lessons.”

Heather Boerner is a science and healthcare journalist based in Pittsburgh. Her book, Positively Negative: Love, Pregnancy and Science’s Surprising Victory Over HIV, came out in 2014.

Published in The Body on February 22, 2018

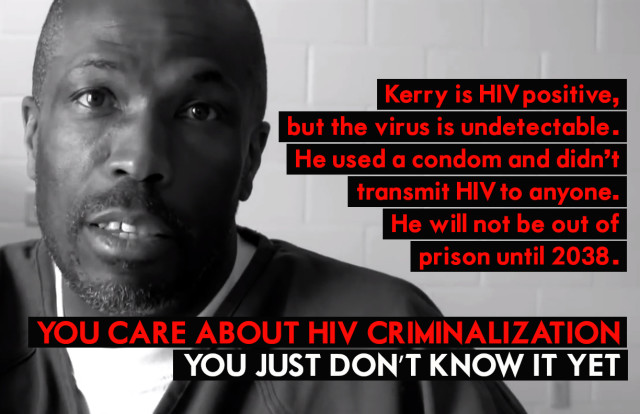

The meeting discussed progress on the global effort to combat the unjust use of the criminal law against people living with HIV, including practical opportunities for advocates working in different jurisdictions to share knowledge, collaborate, and energise the global fight against HIV criminalisation. The programme included keynote presentations, interactive panels, and more intimate workshops focusing on critical issues in the fight against HIV criminalisation around the world.

The meeting discussed progress on the global effort to combat the unjust use of the criminal law against people living with HIV, including practical opportunities for advocates working in different jurisdictions to share knowledge, collaborate, and energise the global fight against HIV criminalisation. The programme included keynote presentations, interactive panels, and more intimate workshops focusing on critical issues in the fight against HIV criminalisation around the world.