This has major implications for criminal HIV exposure law, and possibly also for criminal HIV transmission defence strategies.

This suggests that all jurisdictions that have HIV exposure laws need to rethink their definitions of HIV exposure. In the meantime, it provides an excellent defence for people who are accused of exposure when on a stable regimen with an undetectable viral load.

It also suggests that it should be easier for the police to figure out that the complainant is barking up the wrong tree when accusing a particular individual of being responsible for their HIV infection, if that individual can prove they were on a suppressive anti-HIV regimen at the time.

The statement is remarkable, but no surprise. Doctors and other informed people have been thinking this for several years, but because of the concern that the evidence may be misinterpreted, the data have not been so publicly discussed before.

As you will see, knowing when you are likely to be uninfectious is not easy, and the Swiss statement sidesteps the practical issues that many people are likely to face when making decisions. How can you be sure you, or your partner, doesn’t have an STI, which are often asymptomatic?

I thought readers of this blog might find the article illuminating, anyway, so I include the revelant sections below. The complete newsletter can downloaded here; and a previous article in ATU 118 on the link between treatment and prevention which reviews earlier studies, can downloaded here.

Undetectable’ but infectious?

What the difference between HIV levels in blood and sexual fluids means for infectiousness, by Edwin J Bernard

From AIDS Treatment Update 141, November 2004

Why HAART doesn’t eliminate infectiousness

The idea that taking Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) can reduce infectiousness is not new, and was the subject of an ATU article two years ago (Issue 118, October 2002 ).

In the past few years, scientists have discovered that levels of HIV measured in the blood – which is what we know as viral load testing – are not always the same as levels of HIV measured in sexual fluids. These include cum and pre-cum (semen) in men, sex fluids produced by women, both as lubrication for sex and as ‘ejaculation’ at orgasm, and the coating (mucous membrane) that lines the arse (rectum).

Although many people on HAART with ‘undetectable’ viral loads in their blood also have an ‘undetectable’ viral load in their sexual fluids, and therefore seem less likely to transmit HIV, this is not always the case. Some people with ‘undetectable’ viral loads in their blood have quite high viral load in their sexual fluids, which could be high enough to infect somebody else.

The relationship between levels of HIV in the blood and in sexual fluids is quite complex, and it is thought to be governed by two major issues: the levels of anti-HIV drugs that penetrate into the genital tract, and the presence of inflammation, including, but not limited to, STIs in the genitals.

Defining ‘undetectable’

‘Undetectable’ viral load is one of the aims of anti-HIV therapy. However, the definition of ‘undetectable’ viral load is constantly changing as the technology used to measure viral load improves.

An undetectable viral load result indicates that a specific viral load test cannot find any HIV in a given blood sample. An undetectable result does not mean that the blood is free of HIV. In fact, most people with ‘undetectable’ viral load have HIV in their blood, as well as in blood cells, tissue and bodily fluids.

For each viral load test, there is a lower limit of detection – a limit below which it is not possible to measure the amount of HIV present. Samples with very low levels of HIV, for example below 40 copies/ml, are described as having a viral load that is ‘undetectable’, or ‘below the level of detection’.

This lower threshold depends on the sensitivity of the test. The older, standard tests, which may still be in use in some UK clinics, measure down to 400 or 500 copies/ml. Consequently, an ‘undetectable’ result with a standard test may not mean an ‘undetectable’ result using an ultra-sensitive test, which can measure down to 40 or fewer copies/ml.

Genital tracts, semen and HIV

Genital tracts are the tubes inside the male and female sex organs. The male genital tract is generally considered to a ‘sanctuary site’ for HIV (a place separate from the rest of the body where HIV can hide). This is due to the presence of something called the ‘blood-testis barrier’, which is a layer of cells connected by specialised ‘tight junctions’ that prevent drugs from passing between the blood and areas of the testicles where sperm develops and matures. It is currently thought that HIV found in semen comes from the blood or the lining of the genital tract.

Viral loads in the genital tracts of men

Although most studies show that the majority of men treated with antiretroviral drugs experience parallel declines in viral load in both the blood and semen, all studies have shown considerable individual variation in responses. This means that some men may still have infectious HIV in their semen after their viral load tests indicate that HIV is undetectable in the blood. The following patterns have been observed:

• Viral load becomes undetectable in blood weeks, months or even years before doing so in semen

• Viral load becomes undetectable in blood but not in semen.

• Viral load becomes undetectable in semen but not in blood

• Blood viral load rebounds after a period of undetectability but viral load in semen remains undetectable

In the first case, prolonged HIV production in the genital tract may be explained by the fact that long-lived cells that have been infected by HIV continue to pump out virus copies because anti-HIV drugs cannot adequately penetrate these particular cells.

Another explanation might be that virus production continues because latently infected cells are triggered into virus production by the presence of infections or inflammation.

Dr Tariq Sadiq, Senior Lecturer and Honorary Consultant in HIV and genitourinary medicine at St. George’s Hospital Medical School, offers this explanation: “Many studies have shown that patients on protease inhibitor- or efavirenz-containing regimes have suppressed semen viral loads although there is poor penetration of these drugs into semen. This is probably because penetration [of these drugs] into the tissues of the genital tract, where it is likely to matter most, is not poor,” he continued. “However, another explanation is that the nucleoside analogue components of the regimens, which are often at high levels in the semen, may be adequate to suppress genital tract virus.”

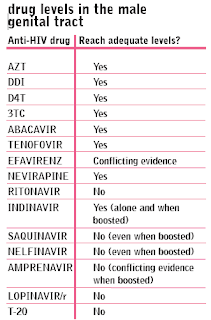

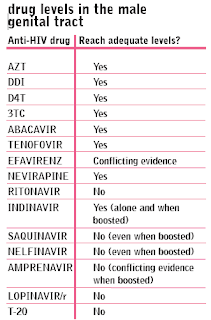

Drug levels are different in the blood and semen

A very recent study has found that many anti-HIV drugs are not reaching high enough levels in semen to prevent HIV from replicating. This, many experts argue, increases the chances that an ‘undetectable’ viral load in the blood many not be providing a full picture of how well the drugs are controlling HIV in the genitals. This could result in higher levels of HIV in sexual fluids than in the blood, even when the viral load is ‘undetectable’ in the blood.

A very recent study has found that many anti-HIV drugs are not reaching high enough levels in semen to prevent HIV from replicating. This, many experts argue, increases the chances that an ‘undetectable’ viral load in the blood many not be providing a full picture of how well the drugs are controlling HIV in the genitals. This could result in higher levels of HIV in sexual fluids than in the blood, even when the viral load is ‘undetectable’ in the blood.

This particular study found that levels of the two most commonly-prescribed drugs in the UK – the non-nucleoside, efavirenz (Sustiva), and the boosted protease inhibitor, lopinavir (Kaletra) – do not reach high enough concentrations to reduce viral load in the male genital tract to ‘undetectable’ levels. The same was found for the ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors amprenavir (Agenerase), and saquinavir (Invirase, Fortovase), as well as the recently-approved fusion inhibitor, T-20 (enfuvirtide, Fuzeon).

With the exception of indinavir, protease inhibitors (PIs) appear to have poor penetration into the genital tract. This is probably due to the protein binding of protease inhibitors and the high protein content of semen, or to the low levels of polyglycoprotein (Pgp), a substance which pumps protease inhibitor molecules out of cells. Pgp is present at very low levels in cells of the brain and testes.

Viral loads in the genital tracts of women

Several large studies have found a strong association between the level of viral load in blood and the level of viral load in women’s sex fluids. However, there is some evidence that antiretroviral therapy may not always result in an undetectable viral load in both blood and vaginal fluid, especially when a genital infection, like urethritis, is present.

In addition, viral load in the female genital tract varies during the course of a menstrual cycle, even among women on anti-HIV treatment. A recent study of viral load changes during the menstrual cycle found that viral load levels in vaginal fluid tended to peak at the time of menstruation and fell to the lowest level just prior to ovulation

Men with ‘undetectable’ viral loads who are the receptive partner in unprotected anal intercourse may have a much higher risk of transmitting HIV than previously thought

HIV in the rectum

Several studies have shown that detectable levels of HIV may persist in the tissue that lines the rectum even after HIV becomes undetectable in the blood. A very recent study that compared levels of viral load in the blood, semen and the coating of the rectal lining (mucous membrane) in men taking HAART found that viral load was, on average, five times higher in semen and 20 times higher in the rectal lining than in the blood.

These findings imply that men who believe themselves to have an ‘undetectable’ viral load and who are the receptive partner in unprotected anal intercourse may have a much higher risk of transmitting HIV than previously thought.

Sexually transmitted infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are important co-factors in the transmission of HIV. Not only can STIs enhance the sexual transmission of HIV by increasing the rate of viral shedding, but HIV infection can also increase susceptibility to STIs.

Dr Sadiq and his colleagues have shown that even where viral load in semen is ‘undetectable’ on HAART, sexually transmitted infections can cause viral load rebound in semen . Conversely, even when viral load is rising in blood, viral load in semen can be brought under control if a sexually transmitted infection is treated, reinforcing the view that the blood and the genital tract are largely independent compartments.

However, Dr Sadiq points out that “the role of genital inflammation may not necessarily be critical. In the work we have done in the UK , a minority of men negative for urethritis and sexually transmitted infections had viral loads considerably higher in semen compared to blood.

“Although it is true that the role of the genital tract as a separate compartment is often exaggerated, more work needs to be done to investigate non-inflammatory factors associated with apparent ‘independent’ genital HIV-1 replication.”

It is important to remember that ‘lower risk’ is a relative term, and does not mean low risk or no risk at all.

Is it sensible to make choices about safer sex based on viral load results?

A recent health education campaign by GMFA (a London-based, volunteer-led gay men’s health organisation), which was aimed at gay men who choose to have anal sex without condoms, included information that suggested that a lower viral load could reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

Although studies in heterosexuals have shown that there is a link between higher viral loads and greater sexual infectiousness, and it does seem logical to assume that a lower viral load would mean a lower risk, the reality is much more complicated.

One the one hand, more information is appearing that suggests many anti-HIV drugs don’t reach high enough levels in sexual fluids to suppress HIV levels in the same way that they do in the blood.

On the other, there is still uncertainty regarding how important anti-HIV drug levels are in sexual fluids, and other experts point the finger at sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as the cause of higher HIV levels in sexual fluids.

What is certain is that a viral load test is simply a ‘snapshot’ of levels of HIV in the blood at the time the test was taken, and that since your viral load can rise and fall at any moment, it could have changed since your last blood sample was taken.

Of course, if you are not taking HAART then you are likely to be more infectious than someone taking HAART.

It is also important to remember that ‘lower risk’ is a relative term, and does not mean low risk or no risk at all.

Given the uncertainties surrounding the effects of HAART on sexual infectiousness, is it really sensible to make choices about safer sex based on viral load results?

KEY CONCLUSIONS

- A significant proportion of people are now making safer sex decisions based on their – or their partner’s – viral load.

- The link between viral load in the blood and viral load in sexual fluids is complicated.

- Levels of some anti-HIV drugs are lower in sexual fluids, and this could mean that there is higher chance of HIV transmission even when viral load is ‘undetectable’ in the blood.

- Levels of HIV in women’s sexual fluids are also affected by their periods.

- Levels of HIV are thought to be twenty times higher in the lining of the arse than in the blood, even in those taking anti-HIV drugs.

- Sexually transmitted infections can increase levels of HIV in sexual fluids, whether you are on anti-HIV drugs or not.

- Making informed choices about safer sex requires taking on board a lot of information, which can change over time.

- The best way to protect your partners from HIV and yourself from STIs is to use condoms for anal and vaginal sex, gloves for fisting, and latex barriers like dental dams for sexual contact that is oral-genital (oral sex) and oral-anal (rimming) sex.