Our Executive Director’s remarks on today’s webinar aimed at philanthropic funders, convened by Funders Concerned About AIDS.

Today, I’ll be connecting two major forces shaping the global HIV response: the wave of criminalisation targeting people living with HIV, people most vulnerable to HIV, and their advocacy organisations, as well as the expanding reach and impact of the Global Gag Order.

Both of these reflect the same problem – the use of law and policy to control bodies, silence communities, and restrict access to health and rights. By the end of this webinar, I hope it will be crystal clear why funding advocacy remains the single highest-impact investment funders can make.

The HIV Justice Network, which I lead, works to end the unjust use of criminal law against people living with HIV worldwide. We document laws and cases, support and train advocates, and co-ordinate the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE coalition – connecting the global to local and back again, linking community organisations, lawyers, and human rights defenders across all regions of the world to reform laws and prosecutorial practices.

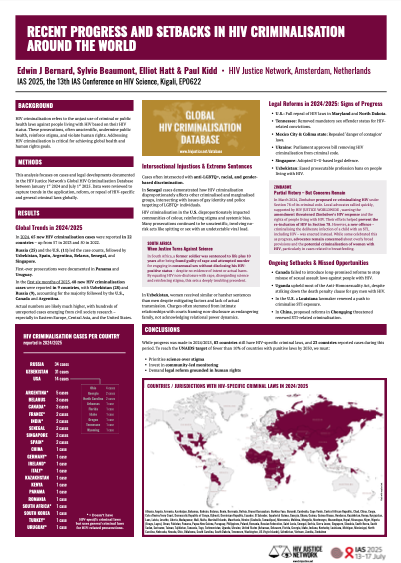

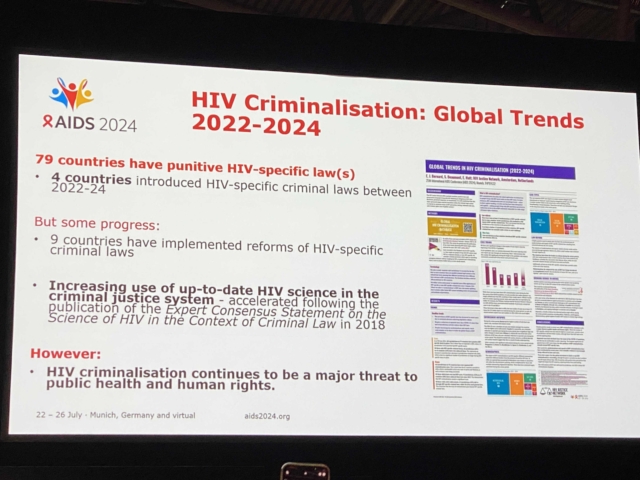

HIV criminalisation remains stubbornly and worryingly widespread. More than 130 countries have used criminal law against people living with HIV accused of non-disclosure, potential or perceived HIV exposure or unintentional HIV transmission. Currently, 83 countries have HIV-specific criminal laws. Others use general criminal laws like “bodily harm”, “endangering health,” and even “attempted murder.”

These laws, and their application, are often based on outdated science and moral panic. They make people living with HIV to be singularly responsible for HIV prevention. They punish us for transmission risks that no longer exist in the era of treatment as prevention – and consider the harm of HIV to be so exceptional they have special laws, or prosecutions, that specifically target people diagnosed HIV-positive. No other communicable disease is treated so problematically in law.

But HIV criminalisation doesn’t exist in isolation. It is part of a broader ecosystem of criminalisation that targets the very communities most affected by HIV – sex workers, migrants, people who use drugs, and LGBTQ+ people. When these populations are criminalised, they are pushed underground, excluded from health services, and made more vulnerable to violence and exploitation.

HIV criminalisation also has a gendered impact. Women are often the first to be diagnosed, especially during pregnancy, and therefore the first to face prosecution. In some countries, pregnant women living with HIV have been charged with endangering their unborn child or accused of transmission through breastfeeding.

Gender-based violence, unequal access to legal representation, and social stigma amplify these injustices. At the same time, the criminalisation of sex work and gender nonconformity exposes women – particularly trans women – to harassment and violence from authorities.

And increasingly, advocacy organisations themselves are being restricted by laws that limit freedom of association, deny foreign funding, or create a chilling effect through so-called “anti-propaganda” or “foreign agent” measures. In more and more countries, simply speaking out against criminalisation is considered to be subversive.

And then there is the Global Gag Order, reinstated and expanded in early 2025 under the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance policy. This policy prohibits non-U.S. NGOs receiving U.S. global health funds from providing, referring for, or even discussing abortion as a method of family planning – even when using their own, non-U.S. resources. It now applies to all U.S. global health assistance, including HIV funding.

For communities and organisations already constrained by criminal laws, the gag order adds another layer of silencing.

• It disrupts integrated HIV and reproductive-health services.

• It forces organisations to choose between funding and integrity.

• It weakens partnerships built over decades of global health cooperation.

• And it amplifies the chilling effect – discouraging advocacy, speech, and even data collection on reproductive rights.

Once again, women and girls bear the brunt. When abortion access is restricted, maternal deaths rise, and the same clinics providing HIV care lose their ability to deliver comprehensive, rights-based health services.

So when we talk about decriminalisation, we’re not just talking about repealing one set of laws. We’re talking about defending the space for civil society, for public health, and for human rights to function at all.

Despite these challenges, advocacy works. Here’s some examples – with a focus on HIV decriminalisation.

• In the US, in the past year alone, Maryland and North Dakota have repealed their HIV-specific criminal laws, while Tennessee removed mandatory sex offender registration for HIV-related convictions.

• In Mexico, again thanks to community leadership, five states have repealed vague “danger of contagion” laws used for HIV criminalisation, with more to come.

• In EECA, civil society in Ukraine is working right now with parliamentary champions to remove an HIV criminalisation law from its criminal code, despite being in the middle of a war.

• In Africa, sustained community advocacy led to the repeal of Zimbabwe’s HIV-specific criminal law and the prevention of a new HIV criminalisation law in Malawi.

But these victories didn’t happen overnight. They resulted from years of partnership between communities, legal and scientific experts, and funders willing to invest in advocacy infrastructure.

Community-led organisations are the foundation of all this progress. We are the early-warning systems when new laws are proposed, and we are the first responders when individuals face charges. We mobilise people living with HIV, key population and women’s networks, and human rights defenders to speak directly with policymakers, prosecutors, and the media.

Philanthropy has a crucial role here. Advocacy funding remains a small fraction of global HIV philanthropy, yet it has exponential impact. Advocacy capacity cannot be switched on only when a law or case hits the headlines. It requires continuity, institutional memory, and relationships built over time.

Funding advocacy protects every other investment in prevention, treatment, and care. Without enabling environments – without legal and policy reform – those investments cannot succeed.

Funders can make the difference by:

• Providing core, flexible, multi-year support that allows community-led groups to stay engaged between crises.

• Investing in coalitions and regional and global networks, like HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE, linking legal, scientific and human rights expertise with communities.

• Supporting data, storytelling, and knowledge translation – turning lived experience and evidence into policy change.

• Protecting civil-society space, especially where advocacy itself is criminalised or restricted.

To close, I want to leave one thought: HIV justice is prevention.

Every law that criminalises people living with HIV, every law that targets LGBTQ+ people, sex workers, people who use drugs, or migrants – and every funding policy that silences reproductive rights – makes the global epidemic harder to end.

Ending AIDS requires more than medicines. It requires dismantling the legal and policy barriers that drive people away from care and from each other.

Ending HIV criminalisation is achievable. We have the science, the evidence, and the community power to do it. What we don’t always have is flexible, sustained, core funding. Advocacy is not optional; it is infrastructure – the connective tissue that holds the HIV response together.

Philanthropy has both the freedom and the responsibility to keep that justice space open – ensuring that evidence, human rights, and community leadership remain at the heart of the global HIV response.

That is how we move from courtrooms to communities – and closer to ending AIDS as a public-health and human-rights crisis.