Translated via Deepl.com – For article in Russian, please scroll down

Knowingly infecting another person with the immunodeficiency virus is a crime, but most criminal cases break up before trial.

Last year, 3,900 Kazakhstani people got the bad news of their HIV test result – 11.5% more than a year earlier (3,500).

Infecting another person with HIV is a criminal offence. Article 118 of Kazakhstan’s Criminal Code provides that if a person infects another person, he or she faces up to five years in prison. The only exception to this is if the HIV-positive person warned his or her partner and the partner volunteered to take the risk.

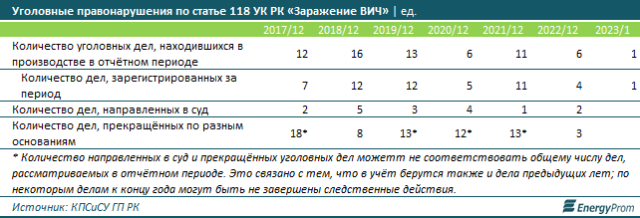

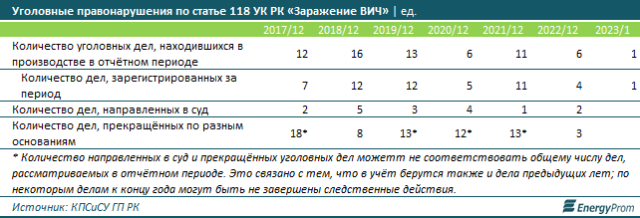

Law enforcement agencies record reports of those infected every year. But compared to the total annual statistics of new patients at AIDS centres, the number of those who report intentional infection to the police is negligible. In 2022, out of 3,900 infected people, only four, or 0.1%, filed a report. In previous years of the five-year period, such appeals were also few: from 5 to 12. This is data from the Committee on Legal Statistics and Special Accounts of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

It is noteworthy that not every such criminal case goes to court. It is not uncommon for cases to be closed on various grounds. This is influenced by many factors, including the evidence base. For example, last year, law enforcement agencies had 6 criminal cases pending. Four of them were received in 2022, and the other two are the previous years’ cases. By the end of the year, only 2 cases were sent to court, and 4 were closed. According to the Legal Statistics Committee report, these 4 cases were terminated on one of the following grounds: lack of corpus delicti, expiration of the statute of limitations, death of a suspect, and “due to refusal to give consent of the prosecutor’s office to prosecute a person who has privileges or immunity from prosecution”. Such persons, according to Chapter 57 of the Criminal Procedure Code, include diplomatic officials, judges, prosecutors and members of parliament. Which of the listed grounds was applied to terminate specifically these criminal cases is not specified in the statistics.

The gender ratio of victims can also be traced in the reports. Most often, it is women who submit statements to the police. Cases of minors being infected with HIV are also recorded. In 2019, 2021 and 2022 the parents of 9 school, college and lyceum students who were infected with HIV contacted the police.

Почему ВИЧ-инфицированные казахстанцы не обращаются в полицию?

Осознанное заражение другого человека вирусом иммунодефицита – преступление, но основная часть уголовных дел распадается до суда.

В прошлом году плохие новости о своем результате ВИЧ-теста узнали 3,9 тыс. казахстанцев — на 11,5% больше, чем годом ранее (3,5 тыс.).

Заражение ВИЧ-инфекцией другого человека — уголовно наказуемое преступление. Статья 118 уголовного кодекса РК гласит: если человек с положительным статусом ВИЧ заразил другого, его могут лишить свободы на срок до пяти лет. Исключение сделают только в том случае, если ВИЧ-инфицированный предупредил партнера и тот добровольно пошел на риск.

Правоохранительные органы ежегодно фиксируют заявления зараженных. Но в сравнении с общей годовой статистикой новых пациентов СПИД-центров, число тех, кто обращается в полицию в связи с умышленным заражением, ничтожно мало. В 2022 году из 3,9 тыс. зараженных заявления написали всего 4 человека, или 0,1%. В предыдущие годы пятилетки таких обращений тоже было немного: от 5 до 12. Это данные комитета по правовой статистике и спецучетам Генпрокуратуры РК.

Примечательно, что далеко не каждое такое уголовное дело доходит до суда. Нередки случаи, когда дела закрывают по разным основаниям. На это влияет много факторов, в том числе доказательная база. Например, в прошлом году в производстве у правоохранительных органов находились 6 уголовных дел. Из них 4 поступили в 2022 году, ещёе 2 — переходящие дела предыдущих лет. До конца года в суд было направлено только 2 дела, а 4 — закрыты. По информации из отчета комитета правовой статистики, производство по этим 4 делам было прекращено по одному из следующих оснований: отсутствие состава преступления, истечение срока давности, смерть подозреваемого, а также “в связи с отказом в даче согласия прокуратуры на привлечение к уголовной ответственности лица, обладающего привилегиями или иммунитетом от уголовного преследования”. К числу таких лиц, согласно главе 57 Уголовно-процессуального кодекса РК, относятся дипломатические работники, судьи, прокуроры, депутаты парламента. Какое из перечисленных оснований было применено для прекращения конкретно этих уголовных дел, в статистике не указывается.

Можно проследить в отчетах и гендерное соотношение потерпевших. Чаще всего заявления в полицию пишут женщины. Фиксируются и случаи заражения ВИЧ-инфекцией несовершеннолетних. В 2019-м, 2021-м и 2022 году в полицию обратились родители 9 школьников, учащихся колледжей и лицеев, которые были заражены ВИЧ.