The Criminal Code potentially considers every HIV-positive citizen to be a criminal, not a person in need of state support.

Why do criminal measures against Tajiks living with HIV contribute to the rapid growth of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the country? What is the practice in neighbouring countries? And, most importantly, how citizens can protect their rights, the correspondent of “Asia-Plus” understood.

The approach to the fight against HIV in Tajikistan, when law enforcement agencies, not doctors, take over, can have the opposite effect. This is the view of Tajik and international human rights activists, as well as the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

According to the Ministry of Health, more than 14 thousand people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) live in the country, almost half of whom do not even know about their HIV-positive status, and their number keeps growing.

On November 9, 2018, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDOW) issued recommendations to Tajikistan, noting that there are a number of barriers in access to health care, which lead to the rapid spread of HIV.

Thus, paragraph 40 contains a recommendation to decriminalize HIV – complete abolition of Article 125 of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan. In the same year, in 2018, 33 criminal cases were initiated against 26 HIV-positive people, and in 2019 this number was increased by at least 6 more cases. These data were voiced by the prosecutor of Khujand Habibullo Vohidov at the coordination council of law enforcement agencies, on 2 May last year.

Since the beginning of 2020, human rights activists of the Centre for Human Rights and ReACT have already registered two such cases.

Article 125 is no longer in effect.

According to the Global Network of PLHIV (GNP+) Stigma and Discrimination Program Manager Alexandra Volgina, Article 125 of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan is taken from the Soviet legislation and reflects the reality of those years when there were no drugs for the disease. HIV rapidly progressed into AIDS, which was in fact a death sentence.

The first part of the 125th article of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Tajikistan speaks about infecting another person with venereal disease by a person who knew that he had this disease. This is despite the fact that antiretroviral therapy (ARV – ed.) completely eliminates the risk of transmission of the immunodeficiency virus and makes a person with HIV completely safe in terms of virus transmission.

It is important to note that antiretroviral therapy works only against HIV and does not protect against other sexually transmitted infections. Therefore, it is important not to forget about condom use as well.

“Criminalisation in itself is a stigma that society perpetuates in law or practice against people living with HIV. They are treated as criminals by default,” says Mikhail Golichenko, a lawyer and international human rights analyst for the Canadian Legal Network.

By placing all responsibility for preventing the transmission of immunodeficiency virus to people living with HIV, the article on criminalization of HIV, in fact, gives society false hope, misleads society when people think that “if HIV is criminalized, I will be warned in any case,” said the lawyer.

In Tajikistan, the diagnosis of HIV is perceived as a threat. This is a big problem, which under the current global scientific base is simply pointless.

The principle of ‘Undefined=Untransferable’ (if a person with HIV receives treatment, the virus in his blood is reduced to a minimum and then he cannot transmit HIV to his sexual partner) is a long-proven scientific fact and a turning point in the history of the fight against HIV/AIDS.

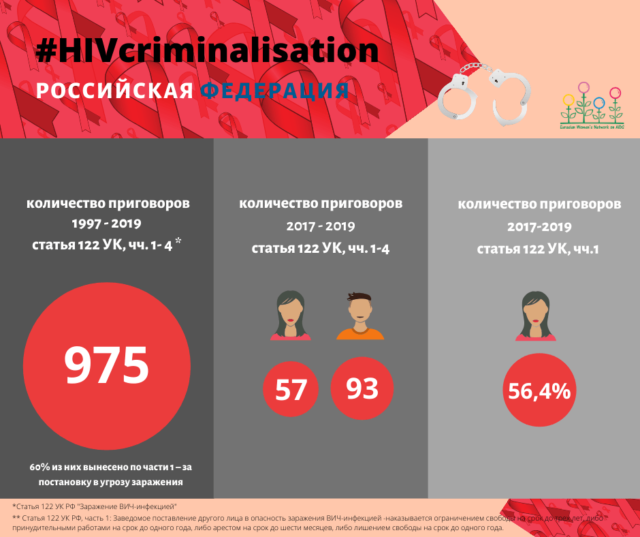

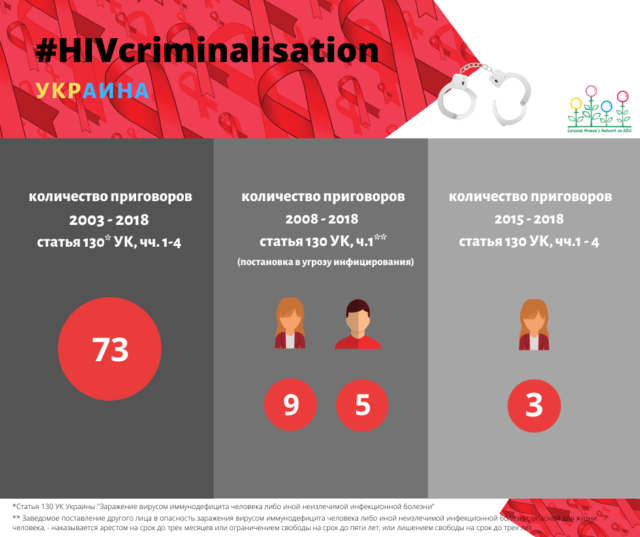

Thus, today HIV-positive women, while receiving treatment, give birth to healthy children, people with HIV live as long as without it. Families where partners with different HIV statuses, without transmitting the disease to each other, live happily, and this happens not somewhere far away, but in neighboring countries: Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Women in a trap

Under article 125 of the Criminal Code, women are mainly recruited in Tajikistan. Human rights expert in the aspect of access to HIV prevention and treatment NGO “Center for Human Rights” Larisa Aleksandrova, says about the stereotype inherent in Tajik society – that HIV infection is mainly caused by sex workers.

In fact, according to the National Programme on Combating HIV Epidemic in 2017-2020, HIV prevalence among sex workers is 3.5%.

Heterosexual sex is the main route of HIV transmission in Tajikistan. In some regions, the proportion of such cases reaches 70%.

Larisa Alexandrova shared real examples of violations of women’s rights from the practice of lawyers of the NGO “Center for Human Rights” Zebo Kasymova and Dilafruz Samadova.

In order to protect personal data, no names are given.

Punishment without a crime

“A 41-year-old resident of Khatlon province was previously convicted under part 2 of article 125 of the Criminal Code and was sentenced to one year in prison in 2018. By court order, she was released early in 9 months due to poor health.

But already in 2019 the woman was repeatedly detained. A criminal case was initiated against her in the same episodes as in 2018. None of the sexual partners in the case were found to be HIV-positive, neither in 2018 nor in 2019. However, the court found the woman guilty again, only under Part 1 of Article 125 of the Criminal Code she was sentenced to 1 year in prison. Under article 71 of the Criminal Code, the court did not impose a suspended sentence, but gave her a probationary period for correction, but under control of her behavior.

Expert opinion: Analysis of this case, according to the lawyer, revealed a low level of professionalism of law enforcement officials, both in terms of knowledge of HIV and in legal proceedings. The reopening of a case on the same episode, on the same facts of a criminal case against a person is a direct violation of the Constitution of Tajikistan and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the expert assures.

– The woman served 9 months for the first time, and under Part 2 of Article 125 of the Criminal Code. Initially, the wrong norm was applied, as Part 2 says about HIV infection. But none of the sexual partners was found to have HIV. Accordingly, there should have been part 1, – sums up Larisa Alexandrova.

A trial without a victim.

“A resident of Khujand, who injected drugs, volunteered for an NGO. A criminal case was initiated on 11 October 2018 under part 1 of article 125 of the Criminal Code. The victims of this case were male. During the trial the man stated that he did not agree with the fact that he was recognized as a victim.

After the initiation of the criminal case on the basis of the commission expert opinion, it was found that the man did not have HIV. At the trial, the lawyer asked questions: “Did the defendant offer to use a condom during sexual intercourse?”, to which the man answered:

“Yes, but I refused. I know that she has this disease, but nevertheless, I love her, I will live with her, I have no complaints or demands to her”.

The legislation of the Republic of Tajikistan refers Article 125 part 1 to the cases of private and public prosecution, which means that these cases are initiated at the request of the victim of the crime, but in case of reconciliation with the accused, the proceedings are not terminated. Despite this, the defendant was sentenced to one year and two months’ deprivation of liberty under article 125, part 1, of the Criminal Code.

Expert opinion: In this case, the person was put in jail despite the fact that she had good medical data. In addition, her sexual partner knew that she had HIV. He did not even submit any application. In that case, the case should have been initiated at least by the prosecutor, not the internal affairs system. And we don’t know who reported this case, either. In this case, the procedure for instituting criminal proceedings and the defendant’s procedural rights were also violated.

The investigator did not even let the attorney or the person under investigation see the indictment. The indictment was presented to the lawyer who defended the woman for the first time at the request of the police. Later the defendant refused to defend him, and she was represented by a lawyer from the NGO “Center for Human Rights”. The lawyer filed a complaint against the investigator with the prosecutor’s office, but the prosecutor’s office found no violations.

The judge did not pay attention to all these violations and passed a sentence, comments the expert Aleksandrova. The case was appealed both to the cassation and supervisory authorities, but the judges considered that there were no violations.

International expert Mikhail Golichenko explained what “knowingly” means from the legal point of view.

Part 1 of Article 125 of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan provides for liability for knowingly putting another person in danger of contracting the human immunodeficiency virus. This article does not provide for such a sign as “infection”. In other words, putting another person in danger of infection is sufficient.

The word “knowingly”, interpreted by lawyer Mikhail Golichenko, means that a person knew in advance about the presence of HIV. Being put in danger, without infection itself, means that the crime is a formal one.

For comparison, the Criminal Code of the Republic of Tajikistan also has actions with the material composition, where the obligatory sign is the public dangerous consequences. For example, murder is a material composition, as for the completed composition it is necessary to have such socially dangerous consequences as the death of a person.

For crimes with formal composition, the only form of guilt can only be direct intent. If a person was aware of public danger of his or her action (inaction) and wanted to commit exactly these actions. If there are signs in the case that, for example, the sexual intercourse without a condom was due to fear of violence by the partner, at the request of the partner. Or for other reasons, which give grounds to conclude that there is no desire to put in danger the infection, it is impossible to prosecute under paragraph 1 of Art. 125 of the Criminal Code. There is no necessary element of the crime – guilt in the form of direct intent.

“No treatment, no punishment”: expert recommendations for Tajikistan

Lawyer Mikhail Golichenko and international human rights expert Aleksandra Volgina are sure that Article 125 is not needed, because intentional HIV transmission is the most likely. In addition, this article is covered by another article of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan – “On causing harm to health”. They are convinced that all parts 1, 2, 3 of Article 125 of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan have long lost their relevance.

In itself, the existence of special responsibility for HIV infection is the stigma attached to people living with HIV as enshrined in the criminal law. And in this sense, Article 125 of the Criminal Code of RT plays a negative role in HIV prevention. In this regard, the best option would be to abolish this norm completely. For rare cases of intentional HIV infection it is possible to apply Article 111 of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan on the liability for intentional harm to health of average gravity.

According to Tatiana Deshko, director of international programs in the Public Health Alliance, in Tajikistan it is necessary to bring medical issues under the control of physicians.

– Let’s look at the results of the “work” of this criminal code article. In Tajikistan, more than one million HIV tests were conducted in 2019, and just over 1,000 new HIV cases were identified – that’s very little. People who have a real risk and HIV infection are simply afraid to be tested. That is not surprising, and it happens everywhere.

“Imagine that you would be isolated for the coronovirus not at home or in a hospital, but in an isolation ward and prison. “Then why would you be tested? Still, medical issues should be dealt with by doctors, not the police – then everything would be in its place and we would become healthier,” says Tatiana Deshko.

Thus, Larisa Aleksandrova said that the telephone hotline of the NGO “Center for Human Rights” also began to be contacted by forensic medical experts on gender reassignment and documents of title for transgender people. Such cooperation began to take shape after trainings for some judges: they begin to refer people living with HIV, who are accused under Article 125 of the Criminal Code, for legal assistance. This suggests that the information and scientifically proven arguments are obvious, as well as the fact that the authorities, receiving more information, are ready to contribute in every way to the reasonable support of human rights.

“The Global Fund confirms its readiness to continue supporting Tajikistan’s efforts in the fight against AIDS in implementing an effective response to HIV based on scientific evidence,” said Alexandrina Iovita, Human Rights Adviser, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to Asia Plus.

– The focus of these activities is to prevent new cases, increase ARV coverage and reduce barriers to human rights violations faced by key populations in accessing services. Evidence and recommendations from technical partners such as UNAIDS and UNDP indicate that overly broad criminalization of HIV prevents people from getting tested and starting ARVs and jeopardizes adherence.

We welcome the increasing focus on public health rather than on punitive approaches. It is public health that is based on effective and humane interventions that are essential when comparing resources spent and results obtained.

Where to go for help for people living with HIV?

The Republic has organizations that provide support and advice to people living with HIV in difficult circumstances. These are SPIN-plus and the Network of Women Living with HIV in Tajikistan.

As for legal assistance, in Tajikistan there is a hotline of NGO “Center for Human Rights”, +992933557755.

“In just 4 months (October 2019-January 2020), 60 people (21 men, 36 women and 3 transgender people) contacted the hotline,” said Larisa Alexandrova.

Any person in a difficult situation due to HIV can contact the hotline and receive free legal advice and / or support for representation in courts, state agencies.

Lawyers who have not previously dealt with such cases, recommended international human rights activist Mikhail Golichenko, should consult with experienced lawyers in advance. Special organizations, such as the Center for Human Rights in Tajikistan, can be contacted to explain what to do in different situations.

You can’t try to do something on your own, better involve allies and organize protection. Lawyers must be clear about what evidence they need to gather in order to do so.

UNAIDS states unequivocally that there is no evidence to support the effectiveness of criminal law enforcement for HIV transmission in preventing HIV transmission. Rather, it undermines public health goals and the protection of human rights. UNAIDS commends country initiatives to review such legislation and repeal it.

Как спасти 14 тысяч таджиков от угрозы тюрьмы, а страну – от эпидемии?

УГОЛОВНЫЙ КОДЕКС РТ КАЖДОГО ВИЧ-ПОЗИТИВНОГО ГРАЖДАНИНА ПОТЕНЦИАЛЬНО РАССМАТРИВАЕТ КАК ПРЕСТУПНИКА, А НЕ ЧЕЛОВЕКА, НУЖДАЮЩЕГОСЯ В ПОДДЕРЖКЕ ГОСУДАРСТВА

Почему уголовные меры против таджиков, живущих с ВИЧ, способствуют стремительному росту эпидемии ВИЧ/СПИДа в стране? Какая практика у соседних стран? И, главное, как гражданам защищать свои права, разбирался корреспондент «Азия-Плюс».

Подход в борьбе с ВИЧ в Таджикистане, когда за дело берутся правоохранители, а не врачи, может дать обратный эффект. Так считают таджикские и международные правозащитники, а также комитет ООН по ликвидации дискриминации в отношении женщин.

По информации Минздрава РТ в стране проживает более 14 тыс. людей с вирусом иммунодефицита человека (ВИЧ), почти половина которых, даже не подозревает о своём ВИЧ-положительном статусе, и их число продолжает расти.

9 ноября 2018 года, комитет ООН по ликвидации дискриминации в отношении женщин (CEDOW) опубликовал рекомендации в адрес Таджикистана, отметив наличие ряда барьеров в доступе к здравоохранению, которые приводят к стремительному распространению ВИЧ.

Так, в пункте 40 содержится рекомендация по декриминализации ВИЧ – полной отмене статьи 125 Уголовного кодекса РТ. В том же 2018 году было возбуждено 33 уголовных дела в отношении 26 ВИЧ-позитивных людей, а в 2019 году к этому числу прибавилось еще, как минимум, 6 дел. Эти данные озвучил прокурор Худжанда Хабибулло Вохидов на координационном совете правоохранительных органов, 2 мая прошлого года.

С начала 2020 года правозащитники ОО «Центра по правам человека» и ReACT зарегистрировали уже 2 таких кейса.

125-я статья уже не работает

По словам менеджера программ по стигме и дискриминации Глобальной Сети ЛЖВ (GNP+) Александры Волгиной, 125 статья в Уголовном кодексе Таджикистана взята из советского законодательства и отражает реальность тех лет, когда еще не было лекарств от этого заболевания. ВИЧ быстро прогрессировал в состояние СПИДа, что являлось фактически смертельным приговором.

Первая часть 125-й статьи УК РТ говорит о заражении другого лица венерической болезнью лицом, знавшим о наличии у него этой болезни. Это притом, что антиретровирусная терапия (АРВ, – ред.) полностью устраняет риск передачи вируса иммунодефицита и делает человека с ВИЧ совершенно безопасным в плане передачи вируса.

Важно отметить, что эта АРВ терапия работает только против ВИЧ и не защищает от других инфекций, передающихся половым путем. Поэтому важно не забывать и об использовании презерватива.

«Сама по себе криминализация — клеймо, которое общество закрепляет в законе или в практике против людей, живущих с ВИЧ. Они рассматриваются как преступники, по умолчанию», – говорит Михаил Голиченко, адвокат, международный аналитик по правам человека Канадской правовой сети.

Возлагая всю ответственность за профилактику передачивируса иммунодефицита на людей, живущих с ВИЧ, статья о криминализации ВИЧ, по сути, дает обществу ложную надежду, вводит общество в заблуждение, когда люди думают, что «если ВИЧ криминализовано, то меня в любом случае предупредят», – отмечает адвокат.

В Таджикистане диагноз «ВИЧ» воспринимается как угроза. Это большая проблема, которая при существующей мировой научной базе просто бессмысленна.

Принцип “Неопределяемый=Непередаваемый” (если человек с ВИЧ получает лечение, у него в крови вирус снижается до минимума и тогда он не может передать ВИЧ половому партнеру) – давно доказанный научный факт и переломный момент в истории борьбы с ВИЧ/СПИДом.

Так, сегодня ВИЧ-положительные женщины, принимая лечение, рожают здоровых детей, люди с ВИЧ живут так же долго, как и без него. Семьи, где партнеры с разными ВИЧ статусами, не передавая болезнь друг другу, живут счастливо, и это происходит не где-то далеко, а в соседних странах: России, Кыргызстане, Казахстане и Узбекистане.

Женщины в западне

В Таджикистане по 125-й статье Уголовного кодекса РТ в основном привлекаются женщины. Эксперт по правам человека в аспекте доступа к профилактике и лечению ВИЧ ОО «Центра по правам человека» Лариса Александрова, говорит о стереотипе, присущем таджикскому обществу – о том, что заражают ВИЧ-инфекцией в основном секс-работницы.

На самом деле, по данным Национальной программы по противодействию эпидемии ВИЧ на 2017-2020 гг. распространенность ВИЧ среди секс-работниц – 3,5%.

Гетеросексуальные половые контакты – основной путь передачи ВИЧ в Таджикистане. В ряде регионов доля таких случаев достигает 70%.

Лариса Александрова поделилась реальными примерами нарушения прав женщин из практики адвокатов ОО «Центра по правам человека» Зебо Касымовой и Дилафруз Самадовой.

В целях защиты персональных данных, имена не указываются.

Наказание без преступления

«41-летняя жительница Хатлонской области ранее была судима по ч.2 статьи 125 УК РТ и приговором суда в 2018 году была осуждена на год лишения свободы. Постановлением суда через 9 месяцев освобождена досрочно в связи с плохим состоянием здоровья.

Но уже 2019 году женщина была повторно задержана. В отношении неё было возбуждено уголовное делопо тем же эпизодам, что и в 2018 году. Ни у одного из проходящих по делу половых партнёров не было выявлено ВИЧ, ни в 2018, ни в 2019году. Однако суд повторно признал женщину виновной, только уже по ч.1 статьи 125 УК РТ ей назначали 1 год лишения свободы. Суд на основании статьи 71 УК РТ условно не применил наказание, а дал ей испытательный срок для исправления, но в условиях контроля за её поведением».

Мнение экспертов: Анализ данного кейса, по словам адвоката, выявил низкий уровень профессионализма сотрудников правоохранительных органов, как по знанию особенностей ВИЧ, так и по судопроизводству. Повторное возбуждение делапо одному и тому же эпизоду, по тем же фактам уголовного дела против человека – прямое нарушение Конституции РТ и Международного пакта о гражданских и политических правах, уверяет эксперт.

– Женщина первый раз отсидела 9 месяцев, причём по части 2 ст.125 УК РТ. Изначально была применена неправильная норма, так как часть 2 говорит о заражении ВИЧ. Но ни у одного из половых партнеров не был обнаружен ВИЧ. Соответственно должна была быть часть 1, — резюмирует Лариса Александрова.

Суд без потерпевшего

«Жительница г. Худжанд, употреблявшая инъекционные наркотики, работала волонтёром в НПО. Уголовное дело было возбуждено 11 октября 2018 года по ч.1. статьи 125 УК РТ. Потерпевшим по этому делу проходил мужчина. В ходе судебного процесса мужчина заявил, что он не согласен с тем, что его признали потерпевшим.

После возбуждения уголовного дела на основании заключения комиссионной экспертизы, было выявлено, что у мужчины отсутствует ВИЧ. На суде были заданы вопросы со стороны адвоката: «Предлагала ли подзащитная использовать презерватив при половом контакте?», на что мужчина ответил:

«Да, но я отказался. Я знаю, что у неё есть это заболевание, но, тем не менее, я люблю её, буду с ней жить, не имею к ней претензии и требований».

Законодательство Республики Таджикистан относит статью 125 часть 1 к делам частно-публичного обвинения, это означает, что эти дела возбуждаются по заявлению лица, пострадавшего от преступления, но в случае примирения его с обвиняемым производство по ним не подлежит прекращению. Несмотря на это, в отношении подсудимой был вынесен приговор – 1 год 2 месяца лишения свободы по ч.1 статьи 125 УК РТ».

Мнение экспертов: В этом случае, человека посадили, несмотря на то, что у неё были хорошие медицинские данные. К тому же о наличии у неё ВИЧ половой партнёр знал. Он даже не подавал никакого заявления. В таком случае дело должно было быть возбуждено, как минимум прокурором, а не системой внутренних дел. И кто сообщил об этом кейсе тоже неизвестно. В данном кейсе был нарушен и порядок возбуждения уголовного, дела и процессуальные права подсудимой женщины.

Следователь даже не дал ознакомиться с обвинительным заключением ни адвокату, ни самой подследственной. Обвинительное заключение было представлено адвокату, которая защищала женщину впервые дни по запросу органов милиции. В впоследствии подсудимаяот его защиты отказалась, и ей был представлен адвокат от ОО «Центр по правам человека». Адвокатом была подана жалоба на следователя в прокуратуру, но прокуратура не нашла никаких нарушений.

Судья не обратил внимания на все эти нарушения и вынес приговор, комментирует эксперт Александрова. Дело было обжаловано и в кассационную, и надзорную инстанции, но и там судьи посчитали, что нарушений нет.

Что значит «заведомо» – с юридической точки зрения объяснил международный эксперт Михаил Голиченко.

Часть 1 ст. 125 УК Таджикистана предусматривает ответственность за заведомоепоставление другого лица в опасность заражения вирусом иммунодефицита человека. В этой статье не предусмотрен такой признак как «заражение». То есть самой постановки в опасность заражения достаточно.

Слово «заведомо», толкует юрист Михаил Голиченко, означает, что человек заранее знал о наличии у него ВИЧ. Поставление в опасность, без наступления самого заражения, означает, что состав преступления формальный.

Для сравнения, в УК РТ также есть действия с материальным составом, где обязательным признаком выступают общественно-опасные последствия. Например, убийство – материальный состав, так как для оконченного состава необходимо наступление такого общественно-опасного последствия, как смерть человека.

Для преступлений с формальным составом единственной формой вины может быть только прямой умысел. Если человек осознавал общественную опасность своего действия (бездействия) и желал совершить именно эти действия. Если в деле есть признаки того, что, например, половой акт без презерватива был по причине страха насилия со стороны партнёра, по просьбе самого партнёра. Либо по другим причинам, которые дают основания для вывода об отсутствии желания поставить в опасность заражения, то привлечь к ответственности по части 1 ст. 125 УК РТ нельзя. Отсутствует необходимый элемент состава преступления – вина в форме прямого умысла.

«Лечить, нельзя наказывать»: рекомендации экспертов для Таджикистана

Адвокат Михаил Голиченко и международный эксперт по правам человека Александра Волгина уверены, что статья 125 не нужна, потому что умышленная передача ВИЧ –редчайшая вероятность. К тому же эта статьяохваченадругой статьей УК Таджикистана – «О причинении вреда здоровью». Они убеждены, все части 1,2,3 ст. 125 УК РТ давно утратили свою актуальность.

Само по себе наличие специальной ответственности за заражение ВИЧ является закрепленной в уголовном законе стигмой по отношению к людям, живущим с ВИЧ. И в этом смысле ст. 125 УК РТ играет негативную роль в вопросах профилактики ВИЧ-инфекции. В этой связи лучшим вариантом была бы отмена данной нормы полностью. Для редких случаев умышленного заражения ВИЧ возможно применении ст. 111 УК РТ об ответственности за умышленное причинение вреда здоровью средней тяжести.

По мнению Татьяны Дешко, директора международных программ в Альянсе общественного здоровья, в Таджикистане необходимо дать медицинские вопросы под контроль медиков.

– Давайте посмотрим на результаты «работы» этой статьи уголовного кодекса. В Таджикистане в 2019 году проведено более миллиона тестов на ВИЧ-инфекцию, а выявлено чуть больше 1 тыс новых случаев ВИЧ – это очень мало. Люди, которые имеют реальный риск и ВИЧ-инфекцию, просто боятся тестироваться. Неудивительно и так происходит везде.

“Представьте, что за короновирус вас бы изолировали не дома или в больнице, а в изоляторе и тюрьме. Пошли бы вы тогда тестироваться? Все-таки медицинскими вопросами должны заниматься врачи, а не полиция, – тогда все станет на свои места и станем здоровее”, – говорит Татьяна Дешко.

Так, Лариса Александрова рассказала, что на телефон горячей линии ОО «Центр по правам человека» начали обращаться также и сотрудники судебно-медицинской экспертизы по поводу изменения пола и правоустанавливающих документов по трансгендерным людям. Такое сотрудничество начало складываться после проведения тренингов для некоторых судей: они начинают перенаправлять людей, живущих с ВИЧ, которые обвиняются по ст.125 УК РТ, за правовой помощью. Это говорит о том, что информирование и научно доказанные аргументы очевидны, а также о том, что представители власти, получая больше информации готовы всячески способствовать разумному сопровождению прав человека.

«Глобальный фонд подтверждает свою готовность продолжать поддержку деятельности Таджикистана в борьбе со СПИДом в применении эффективных мер ответа на ВИЧ, основанных на научно-доказанных данных, – сказала «Азия-Плюс» Александрина Иовита, советник по правам человека, Глобального фонда для борьбы со СПИДом, туберкулёзом и малярией.

– Фокус этой деятельности направлен на предотвращение новых случаев, расширение охвата АРВ и снижение барьеров, связанных с нарушением прав человека, с которыми сталкиваются представители ключевых групп в контексте получения доступа к услугам. Фактические данные и рекомендации от технических партнеров, таких, как ЮНЭЙДС и ПРООН, указывают на то, что чрезмерно широкая криминализация ВИЧ не позволяет людям проходить тестирование и начинать АРВ, а также ставит под угрозу приверженность.

Мы приветствуем все больший фокус на общественном здравоохранении, а не на карательных подходах. Именно общественное здравоохранение основано на эффективных и гуманных мерах, представляющих большую значимость при сравнении затраченных ресурсов и полученных результатов».

Куда обратиться за помощью людям, живущим с ВИЧ?

В республике работают организации, которые оказывают поддержку и консультирование людям, живущим с ВИЧ, оказавшимся в сложных жизненных обстоятельствах. Это СПИН-плюс и Сеть женщин, живущих с ВИЧ в Таджикистане.

Что касается правовой помощи, в Таджикистане работает горячая линия ОО «Центра по правам человека», +992933557755

«Только за 4 месяца (октябрь 2019-январь 2020) на горячую линию обратились 60 человек (21 мужчина, 36 женщин и 3 трансгендерных человека)», – говорит Лариса Александрова.

Любой человек, оказавшись в сложной ситуации, в связи с ВИЧ, может обратиться на горячую линию и получить бесплатно правовую консультацию и/или поддержку по представительству в судах, государственных органах.

Адвокаты, которые ранее не занимались подобными делами, рекомендует международный правозащитник Михаил Голиченко, должны заранее проконсультироваться с опытными юристами. Можно обратиться в специальные организации – такие как ОО «Центр по правам человека в Таджикистане», чтобы им могли разъяснить, как быть в разных ситуациях.

Нельзя пытаться что-то делать своими силами, лучше привлечь союзников и организовать защиту. Адвокат должен четко знать, какие доказательства для этого необходимо собрать.

ЮНЭЙДС однозначно заявляет, что нет никаких данных, подтверждающих эффективность применения уголовного законодательства в отношении передачи ВИЧ – для предотвращения передачи ВИЧ. Наоборот, такое применение подрывает цели общественного здравоохранения и защиту прав человека. ЮНЭЙДС высоко оценивает инициативы стран по пересмотру такого законодательства и его отмене.