In The Life’s 2011 report, Legalizing Stigma, was the first on a national US TV channel (PBS) to look at the issue of HIV criminalization from the perspective of people targeted by criminal laws. The segment led to public education efforts, beginning with the first ever Congressional Briefing on this issue.

Sweden: Campaign to change draconian, punitive policies for PLHIV aiming for Government review

In Sweden, the Communicable Diseases Act requires people with diagnosed HIV to disclose in any situation where someone might be placed at risk and to also practise safer sex (which, in Sweden, means using condoms – the impact of treatment on viral load and infectiousness is not yet considered to be part of the safer sex armamentarium.)

But in Sweden you’re damned if you do (disclose) and damned if you don’t because Sweden is one of several countries in western Europe – including Austria, Finland, Norway, and Switzerland – where people with HIV can be (and are) prosecuted for having consensual unprotected sex even when there was prior disclosure of HIV-positive status and agreement of the risk by the HIV-negative partner. Sweden uses the general criminal law for these prosecutions of which there have been at least 40 – out of an HIV population of around 5,000.

And if you think the Swedes aren’t being overly harsh, then watch the harrowing documentary, ‘How Could She?’ about a young woman, Lillemore, who was in such denial that she did not tell anyone that she was HIV-positive (including the doctors who delivered her two children). Even though both children were born HIV-free, and no-one was harmed by her non-disclosure, following the break-up of her marriage, her ex-husband reported her to the authorities and she was sentenced to 2 1/2 years in prison.

Fortunately, most of these countries with overly-draconian policies towards people with HIV are well advanced in the process of examining (and hopefully, changing for the better) such laws and policies.

Norway has set up a special committee to examine whether its current law should be rewritten or abolished: its recommendations are due in May.

Switzerland is currently revising its Law on Epidemics, to be enacted later this year, and, according to my sources, the latest version appears to be mostly consistent with UNAIDS’ recommendations.

In 2010, Austria’s Ministry of Justice conceded that an undetectable viral load is considered a valid defence, even if they say individual judges can ignore their recommendation, although much more could still be done to remove the legal onus for HIV prevention on people with HIV.

And Finland has established an expert group on HIV/AIDS within the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare with the aim to ensure legislative reform, and address laws and polices that reinforce stigma and discrimination.

But Sweden – which has the most HIV-related prosecutions per capita of people with HIV in Europe (and probably the world) and that’s not including the 100+ more people with HIV who have been forcibly detained and isolated under the Communicable Diseases Act – is lagging behind, and continues to enforce its ‘human rights-unfriendly’ policies.

Fortunately, civil society is fighting back. In 2010, HIV-Sweden, RFSU (the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education) and RFSL (the Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights) began a three-year campaign to raise awareness and advocate against Sweden’s over-punitive HIV-related policies.

A recent conference held just before World AIDS Day put together by the campaign and attended by police, prosecutors and politicians highlighted the many human rights concerns over Sweden’s current laws and policies. I was honoured to be one of only two non-Swedes to speak at the meeting (which was held mainly in Swedish – so a big thank you to Elizabeth, my personal “whisper” translator) – you can see the agenda and download a copy of my presentation here.

|

| Download Google translated version of full article here |

The meeting and associated campaign received a lot of press coverage, including the front page of the biggest circulation morning paper in Sweden on World AIDS Day.

|

| Download ‘HIV, Crime and Punishment’ |

At the meeting, HIV Sweden, RFSL and RFSU launched an important new manifesto, ‘HIV, Crime and Punishment‘ that clearly explains what the problems are for people with HIV (and public health) in Sweden and asks for three actions from the Swedish Government:

- A review of Swedish law, including the Communicable Disease Act as well as the application of the criminal law to HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

- An endorsement by Sweden of the 2008 UNAIDS Policy Brief on the criminalisation of HIV transmission, which says that criminal prosecutions should be limited to unusually egregious cases where someone acted with malicious intent to transmit HIV, and succeeded in doing so.

- A renewed, clear focus of Sweden’s National HIV Policy on a human rights-based approach to HIV prevention, care, support and treatment, and sex education.

Let’s hope that Sweden’s policymakers take heed. After all, how can a country which supports UNAIDS’ global efforts, and is perceived to be a global champion for human rights around the world treat people with HIV in its own country as second class citizens?

Don’t think Sweden is that bad? Check out the 2005 case of Enhorn v Sweden at the European Court of Human Rights which found that Sweden had unlawfully isolated a man with HIV for a total of seven years, a violation of Article 5 § 1 of the Convention, ‘right to liberty and security of person’.

Canada: Urgent – support the call for prosecutorial guidelines in Ontario

Canada is facing its most critical point in the history of criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure since the Supreme Court’s 1998 Cuerrier decision which found that not disclosing a known HIV-positive status prior to sex that poses a “significant risk” of HIV transmission negates the other person’s consent, rendering it, in effect, a sexual assault.

In February 2012, the Supreme Court will hear two cases – Mabior and ‘DC’ – that will re-examine whether Cuerrier remains valid in the light of inconsistent lower court decisions regarding what constitutes a “significant risk” of HIV transmission in the context of sexual transmission, especially when the person with HIV wears a condom and/or has an undetectable viral load due to effective antiretroviral therapy.

The main thrust of the arguments from both sides is that the “significant risk” test is unfair and should be reassessed. However, Manitoba’s Attorney General (who is appealing the Manitoba Court of Appeal’s decision to partially acquit Mr Mabior due to his using a condom or due to his undetectable viral load when not using a condom) is arguing in its appellants factum that the only fair legal test is whether or not a person with HIV disclosed before any kind of sexual contact, because figuring out whether the risk at the time was significant enough is too complicated. It also argues that such non-disclosure should be charged as aggravated sexual assault, which carries a maximum 14 year sentence for each episode of unprotected sex without disclosure.

Lindsay Sinese, in excellent recent blog post from The Court, examining both Mabior and DC as they head to the Supreme Court, highlights what is already problematic about attempting to prove non-disclosure in cases that are often based on he said/(s)he said testimony.

In the jurisprudence surrounding HIV criminalization, th[e DC] case reads like frustrating déja vu, exhibiting several characteristics common to many of the more than 130 people living with HIV who have been subject to criminal charges. Namely, the parties rarely agree on the facts of the case, particularly on whether or not the sexual intercourse in question was protected, how many times it occurred and under what circumstances. These critical facts obviously present significant obstacles with regards to proof and the situation devolves in a “he said, she said” scenario.

The inability to prove the key elements upon which the case turns leaves the outcome to be very unpredictable. As a result, the cases tend to hinge on the credibility of the parties, the determination is, at best, a loose science, and, at worst, an exercise in hunch-based guess work.

Another problematic factor in this realm of prosecution is that charges are frequently laid after the dissolution of a relationship. It could be argued that some of the complaints may be brought for vengeful and vexatious purposes. By leaving HIV positive people vulnerable to criminal prosecution, we are sanctifying the punishment of an already vulnerable group, and pushing this community further onto the fringes of society.

The greatest disappointment, however, is that Ontario’s Attorney General has joined with the AG’s of Manitoba and Quebec (where DC was tried) by obtaining intervener status.

In an application this week to the Supreme Court of Canada, the Office of the Ontario Attorney General asks to be granted intervener status in an upcoming high-profile case revolving around those living with the human immunodeficiency virus, which can lead to AIDS. It argues that the current legal standard the courts must meet has led to different interpretations across the country, resulting in “uncertainty and unfairness” in the Canadian legal system. To remedy this, the government argues that criminal liability should be based only on whether or not someone disclosed his or her HIV-status before engaging in sexual activity and not just on the safety risks they pose.

This is a major slap in the face to the Ontario Working Group on Criminal Law and HIV Exposure (CLHE) campaign urging Ontario’s Attorney General to develop prosecutorial guidelines for Crown prosecutors handling allegations of HIV non-disclosure. The working group produced an excellent report in June 2011 which calls for restraint in HIV non-disclosure prosecutions and provides detailed legal and practice guidance covering general principles; bail; scientific/medical evidence and experts; charge screening; resolution discussions; sentencing; and complainant considerations. The report, available here, is a must-read for all advocates working in their own countries to obtain prosecutorial guidelines.

In a recent email, CLHE co-chairs Ryan Peck and Anne Marie DiCenso outline the problems they perceive with the promises made by the Ministry of the Ontario Attorney General’s and its current position as intervener.

In December 2010, Chris Bentley, the former Attorney General, promised to develop guidelines. Since then, the Ministry of the Attorney General has not informed CLHE when it will be honouring its commitment to develop prosecutorial guidelines, and has not responded to CLHE’s guideline recommendations. CLHE’s recommendations are at http://www.catie.ca/pdf/Brochures/HIV-non-disclosure-criminal-law.pdf.

It is particularly troubling that the Attorney General, after committing to develop guidelines, has filed materials at the Supreme Court of Canada calling upon the Court to rule that people living with HIV must disclose their HIV status before any sexual activity whatsoever, and that not disclosing should be prosecuted as an aggravated sexual assault, which is one of the most serious offences in the Criminal Code.

When asked about this position, former Attorney General, Chris Bentley, indicated that although the intervention materials advocate for the elimination of the current significant risk test, the Attorney General of Ontario has no intention of taking such a position at the Supreme Court of Canada.

It is vital that the Attorney General fulfill the promises made.

But, as of today, we have not received any guarantee from the new Attorney General, John Gerretsen, that the Ministry of Attorney General will amend its intervention materials and take the position that people living with HIV should not be prosecuted when there is no significant risk of HIV transmission.

The Ministry of the Attorney General has until December 20 to submit its final materials to the Supreme Court. While preparing the materials, the new Attorney General, John Gerretsen, needs to know that the community is mobilized and is watching him.

The most effective way to do this is for everyone who reads this post to endorse the call for guidelines. While the Ministry may care more about Ontarians signing the call, I have had it confirmed from my contacts at CLHE that signatures from other jurisdictions would be very helpful.

When you sign the call the following email (which you can personalise if you want) will be sent to the new Attorney General, John Gerretsen, urging him to develop guidelines by December 31, 2011.

Dear Minister Gerretsen,

I am writing to congratulate you on your new post as Attorney General, and to urge you to take action on an important issue.As you know, your predecessor, the Honourable Chris Bentley, committed in December 2010 to draft guidelines for criminal cases involving allegation of non-disclosure of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

I urge you to draft these much-needed guidelines by December 31, 2011. I also urge you to take into account the broad-based community input provided to the Ministry of Attorney General by the Ontario Working Group on Criminal Law and HIV Exposure (the Working Group). In spring 2011, the Working Group consulted over 200 people — people living with HIV/AIDS; communities affected by HIV; legal, public health, criminal justice and scientific experts; health care providers; and advocates for women’s rights in the context of sexual violence and the criminal justice system. In June 2011, the Working Group provided the Ministry with their Report and Recommendations based on these consultations.

I trust that you will draft guidelines by December 31, 2011, and that you will provide the Working Group and its constituents with an opportunity to review and provide input on this draft.

Guidelines are urgently needed to ensure that HIV-related criminal complaints are handled in a fair and non-discriminatory manner.

Please take action.

Denmark: HIV to be removed from Article 252, but new statute wording may re-criminalise non-disclosure without “suitable protection”

Denmark’s new Minister of Justice Morten Bødskov is now taking formal steps to remove references to HIV from Article 252 of the Danish Penal Code which means that, for the time-being, HIV exposure and transmission is decriminalised.

The news was released in a letter dated 8 November and provided to me by AIDS-Fondet (Danish AIDS Foundation).

That’s the good news. The not-so-good news is that the working group set up to examine whether or not there should be a new HIV-specific law is proposing new wording for a statute that would criminalise non-disclosure of known HIV-positive status, unless “suitable protection” is used for vaginal or anal intercourse.

Their recommendations will be considered during a consultation period which ends on 6 December 2011. Members of all branches of the criminal justice system are being consulted as well as HIV and human rights organisations.

Denmark prosecuted its first HIV-related criminal case in 1993, but the Supreme Court found in 1994 that the wording of the existing law (“wantonly or recklessly endangering life or physical ability”) did not provide a clear legal base for conviction. The phrase “fatal and incurable disease” was added in 1994, and HIV was specified in 2001. After at least 15 prosecutions, the former Minister of Justice suspended the law earlier this year due to concerns that it no longer reflected the realities of HIV risk and harm.

The working group has produced a 20 page memo which states that the legal basis for the current statute no longer exists and, therefore, it should be repealed. They particularly emphasise the increased life expectancy for people on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and conclude that HIV is no longer “fatal” (although it is still “incurable”).

The lifespan of a well-treated HIV-infected individual does not differ from the age and gender-matched background population, and…timely treatment is now as effective and well tolerated (i.e, usually without significant side effects) so that an estimated 85-90 per cent of patients can live a normal life, as long as they adhere to their treatment on a daily basis.

The memo then examines HIV-related risk (including the impact of ART on risk) and harm and highlights that it is the estimated 1000 undiagnosed individuals (out of an estimated total of 5,500 people with HIV in Denmark) that are more likely to be a public health concern.

It notes that using HIV as a weapon in terms of violent attacks with needles; rape; or sex with minors could still be an aggravating factor during sentencing under other, revelent criminal statutes. However, a 1994 Supreme Court ruling found that general criminal laws, such as those proscribing bodily harm or assault could not be applied to sexual HIV exposure or transmission.

The memo then presents arguments for and against a new statute. It argues that any new law should not proscribe ‘HIV exposure’, since it notes, the risks of HIV transmission on ART “are vanishingly small” and so it would be very difficult for any prosecutor to prove that someone was exposed to HIV under these circumstances.

Since ART is now considered to be effective as condoms in reducing HIV transmission risk, the working group considered whether it might be possible to only criminalise untreated people who have unprotected sex, but worry that proving that a person on ART was uninfectious at the time of the alleged act would be too difficult.

Similarly, although they consider the UNAIDS recomendation to only criminalise intentional transmission via non-HIV-specific laws, they were concerned that proving such a state of mind would be extremely difficult.

They conclude that if a new statute were to replace Article 252 it should criminalise non-disclosure unless “suitable protection” is used. (This potentially leaves it open to argue that ART as well as condoms could be considered “suitable protection.”) Their suggested wording is

§ x. Whoever has a contagious, sexually transmissible infection which is incurable and requires lifelong treatment and has intercourse with a person without informing them of the infection, or using suitable protection, is punishable by a fine or imprisonment for up to 2 years.

They note, however, that since the harm of HIV is reduced due to the impact of ART that the current maximum sentence of 8 years in prison should be reduced to 2 years and “the normal penalty should be a fine or a short (suspended) term of imprisonment.”

Although they are not necessarily recommending this new statute, the working group warns that “decriminalisation…may have unintended, negative consequences” and that public health and community based HIV organisations alike should ensure that health education about HIV and how to avoid it continues unabated because “it is important to send the message that HIV is still a disease that must be taken seriously.”

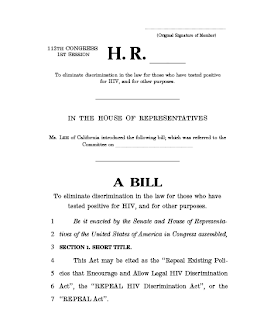

US: Positive Justice Project Members Endorse REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act

Press Release

New York, September 23, 2011 – Members of the Positive Justice Project, a national coalition dedicated to ending the targeting of people with HIV for unreasonable criminal prosecution, voiced their support for the REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act that Congresswoman Barbara Lee (D-CA) introduced today.

|

| Download the REPEAL ACT here |

The bill calls for review of all federal and state laws, policies, and regulations regarding the criminal prosecution of individuals for HIV-related offenses. It is the first piece of federal legislation to take on the issue of HIV criminalization, and provides incentives for states to reconsider laws and practices that unfairly target people with HIV for consensual sex and conduct that poses no real risk of HIV transmission.

The proposed bill is being met with widespread support. Ronald Johnson, Vice President for Policy and Advocacy at AIDS United (a Positive Justice Project member) says, “AIDS United supports the REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act. It’s long past time for a review of these criminal and civil commitment laws and we welcome Representative Barbara Lee’s efforts to help local and state officials understand and make needed reforms.”

Thirty-four states and two U.S. territories now have laws that make exposure or non-disclosure of HIV a crime. Sentences imposed on people convicted of HIV-specific offenses can range from 10-30 years and may include sex offender registration even in the absence of intent to transmit HIV or actual transmission. Though condom use significantly reduces the risk of HIV transmission, most HIV-specific laws do not consider condom use a mitigating factor or as evidence that the person did not intend to transmit HIV.

For example, a man with HIV in Iowa received a 25-year sentence for a one-time sexual encounter during which he used a condom and HIV was not transmitted; although the sentence was eventually suspended, he still was required to register as a sex offender and is barred from unsupervised contact with children. People also have been convicted for acts that cannot transmit HIV, such as a man with HIV in Texas who currently is serving 35 years for spitting at a police officer.

“The Repeal HIV Discrimination Act relies on science and public health, rather than punishment, as the lead response to HIV exposure and transmission incidents. It embodies the courage and leadership needed to replace expensive, pointless and punitive reactions to the complex challenge of HIV with approaches that can truly reduce transmission and stigma,” remarked Catherine Hanssens, Executive Director of the Center for HIV Law and Policy and a founder of the Positive Justice Project

Representative Lee’s bill requires designated officials to develop a set of best practices, and accompanying guidance, for states to address the treatment of HIV in criminal and civil commitment cases. The bill also will provide financial support to states that undertake education, reform and implementation efforts. A fact sheet created by The Center for HIV Law and Policy, AIDS United, Lambda Legal and the ACLU AIDS Project summarizes the problems with HIV criminalization and the measures the REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act takes to address them.

“The REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act will serve a critical role in educating Members of Congress and the public about the harmful and discriminatory practice of criminalizing HIV. Such state laws often originated during times when fear and ignorance over HIV transmission were widespread, and serve to stigmatize those who are living with HIV. Our criminal laws should not be rooted in outdated myths. Rep. Lee is to be commended for her tireless leadership on behalf of those who are living with HIV/AIDS,” said Laura W. Murphy, director of the ACLU Washington Legislative Office.

Scott Schoettes, HIV Project Director at Lambda Legal summarized the support of many. “Lambda Legal wholeheartedly supports the ‘REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act.’ It is high time the nation’s HIV criminalization laws were reformed to reflect the modern reality of living with HIV, both from medical and social perspectives. Except for perhaps the most extreme cases, the criminal law is far too blunt an instrument to address the subtle dynamics of HIV disclosure.”

Other PJP member statements in support of the REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act:

“The HIV Prevention Justice Alliance expresses our strong commitment to HIV decriminalization and ongoing support for Representative Barbara Lee’s Repeal HIV Discrimination Bill. We have seen how the criminalization of HIV has increased instead of reduced HIV stigma and panic. We have also seen how the criminalization of HIV further targets communities – black, Latino/a, queer, transgender, low income, sex worker, homeless, drug user – which are already disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDS and mass incarceration. We applaud Congresswoman Lee’s courageous effort to support resiliency and dignity of HIV positive people and loved ones and affirm her continued support for prevention justice and decriminalization.”

—Che Gossett, Steering Committee Member, HIV Prevention Justice Alliance

“This is definitive legislation in the national fight to end HIV discrimination and for survivors of criminalization.”

—Robert Suttle, Member of Louisiana AIDS Advocacy Network (LAAN)

“A Brave New Day is in full support of Rep. Barbara Lee’s Anti-Criminalization bill.”

—Robin Webb, Executive Director of A Brave New Day

“We feel strongly that many such statutes violate human rights, are constitutionally vague, are irrational, and violate the laws of science in that they attempt to characterize known scientifically proven facts about transmission as irrelevant to the issue of potential damage and danger. We feel that people’s ‘fear’ if irrational cannot provide a basis for a criminal statute or prosecution under same and that a statute cannot be both legal and illogical.”

—David Scondras, Founder/CEO, Search For A Cure

For a list of organizations supporting the REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act, click here.

Guyana’s Special Select Committee of Parliament on the Criminal Responsibility of HIV Infected Individuals has chosen not to create an HIV-specific criminal law

UN Team on AIDS lauds Guyana 09-Sept-2011 – says ‘Guyana gets it right’ by not criminalising HIV GUYANA’S Special Select Committee of Parliament on the Criminal Responsibility of HIV Infected Individuals has chosen not to make the transmission of HIV a criminal act.The Joint United Nations Team on AIDS, coordinated by the United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) congratulates the Parliamentary Committee for its mature and measured decision.

This latest parliamentary decision clears the way for Guyana’s HIV response to continue proceeding in a rational and productive direction.

(The full Report of the Special Select Committee to the Guyana Parliament are available online and the Speech of Honourable Dr. Leslie Ramsammy, Minister of Health quoted at: https://www.kaieteurnewsonline.com/2011/09/20/franklin-does-about-face-on-motion-to-criminalize-willful-transmission-of-hivaids/

Expert meeting reviews scientific, medical, legal and human rights issues related to the criminalization of HIV exposure and transmission

World leading scientists and medical practitioners joined legal experts and civil society representatives to discuss the scientific, medical, legal and human rights aspects of the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission. The meeting, organized by UNAIDS, took place in Geneva from 31 August to 2 September.

Denmark: HIV criminalisation exports stigma, writes Justice Edwin Cameron

Denmark’s leading broadsheet newspaper, Politiken, last week published an article by Justice Edwin Cameron of the South African Constitutional Court congratulating Denmarks’ recent suspension of its HIV-specific criminal statute, and asking that it considers abolishing it altogether – otherwise it risks being emulated in low-income settings that follow the country’s example of an otherwise strong human rights record.

Justice Cameron wrote a similar article for a Norwegian newspaper in 2009 which led to a rethink of the use of Paragraph 155 (the ‘HIV paragraph’) and the establishment of an independent commission to explore the article’s revision.

I hear from my contacts in Denmark that there already some signs that the article has gained the attention of some high-level government ministers concerned about Denmark’s standing in the global HIV community.

Let’s hope it has a positive impact on Denmark’s ongoing government working group currently considering whether the only HIV-specific law in Western Europe should be revised or abolished.

The full text of Edwin Cameron’s article in English is below. The Danish original can be found here.

Debate: Denmark exports stigma

AIDS Foundation

Politiken 8th June 2011, Culture, page 6

INTERNATIONAL COMMENTARY: Danish HIV–law is in conflict with the UN

by Edwin CameronWhen South Africans think of Denmark, we see a country with the highest humanitarian standards that others look up to. I was therefore disturbed to realise recently that Denmark has one of the world’s harshest laws criminalising HIV: Penal Code Section 252, paragraph 2. This provision makes criminal anyone with a life threatening and incurable communicable disease who wilfully or negligently infects or exposes another to the risk of infection.

What is notable about the Danish law is that it includes mere exposure—which means that a person may be guilty even though there is no actual transmission. The penalty is severe—up to eight years of imprisonment. Today the law only covers people living with HIV — a vulnerable group that experiences much discrimination.

Denmark is among the world’s most generous contributors to UNAIDS, the UN agency that works to mitigate the impact of this mass worldwide epidemic. In addition, Denmark has signed the declaration on HIV and AIDS, adopted at the UN Special Session. But Denmark’s penal code is in conflict with both UNAIDS and the UN Declaration’s position.

UNAIDS has called on governments to limit criminalisation to cases where “a person knows his HIV positive status, acts with the intent to transmit HIV and actually transmits HIV’. In contrast, the Danish penal provision is precisely the kind of legislation that UNAIDS warns against.

We know that many developing countries pay attention to the more developed countries’ laws when they formulate their own. In Africa, my own continent, an increasing number of countries have adopted laws that criminalize HIV, with devastating consequences – not least for women. By maintaining its own discriminatory legislation Denmark in effect exports stigma.

But there are strong reasons why criminal laws and prosecutions are bad policy when it comes to AIDS.

1: Criminalisation is ineffective in relation to limiting the spread of HIV. In most cases the virus spreads when two people have sex, neither of them knowing that one of them has HIV. The fact that a penal provision is of no use here is a good reason to doubt whether it should remain on the statute book.

2: Criminal laws and prosecutions are poor substitutes for measures that can really control the epidemic. Experience shows us that well-considered public health programmes that offer counseling, testing and treatment are far more effective tools to prevent the spread of HIV.

3: Criminalisation does not protect women, but makes them victims. In Africa, most of those who know their HIV status are women, because most tests take place at antenatal health care sites. These laws have rightly been described as part of a ‘war on women’.

4: Many of these new laws in Africa, which are being adopted partly on the strength of Western European precedents, are extremely poorly drafted. For example, according to the ‘Model Law’ that many countries in East and West Africa have adopted, a person who is aware of being infected with HIV must inform “any sexual contact in advance” of this fact. But the law does not define “any sexual contact.” Is it holding hands? Kissing? Nor does the law say what “in advance” means.

5: Criminalisation increases stigma. From the first AIDS diagnosis 30 years ago, HIV has carried a mountainous burden of stigma. One overriding reason: the fact that HIV is sexually transmitted. No other infectious disease is viewed with as much fear and repugnance. It is tragic that it is stigma that drives criminalisation.

6: Criminalisation has a deterrent effect on testing. AIDS is now a medically manageable disease, but why would someone want to know their HIV status when that knowledge may lead to prosecution? Criminalisation assumes the worst about people with HIV and punishes their vulnerability.

Denmark’s legislation also makes it difficult for a country that ought to be a world leader in non-discrimination to confront other countries’ laws. For example, Denmark has contributed constructively in the international movement to abolish the travel restrictions for people with HIV.

The recent decision by the Danish Justice Minister, Lars Barfoed, to suspend the Danish Criminal Code provision on HIV on the grounds that people living with HIV on treatment today live much longer lives and the risk of transmission of the virus to others is much reduced is certainly a step in the right direction. I congratulate the Danish Government on this decision. The very positive developments in HIV treatment is indeed a good reason to radically reconsider whether Penal Code 252. 2 should exist at all.

Penal Code provisions are a piece of the puzzle that shows how a country treats its citizens. Let us fight stigma, discrimination and criminalisation – and fight for common sense, effective prevention and access to treatment. Only in this way can we fight this global epidemic.

Edwin Cameron is a judge of South Africa’s Constitutional Court who is himself living with HIV.

Belgium: First criminal conviction under poisoning law, advocates caught unawares

Last week saw the first successful prosecution for criminal HIV transmission in Belgium. The case surprised the main HIV support organisation, Sensoa, who were only informed of the case by the media because neither complainant nor defendant (both of whom were African migrants) had contacted them for support or legal advice.

Details of the case are relatively sketchy and only available in Dutch-language news reports, available here (English translation via Google) and here (English translation via Google). A more detailed news story appeared following the man’s conviction in De Standaard, but I am unable to translate it. They have been supplemented via a colleague working on the issue at Sensoa.

The facts in brief.

A 54 year-old man, originally from Angola, was found guilty of ‘knowingly infecting’ his former wife (originally from Congo, and thought to be significantly younger) with HIV via the existing criminal law of poisoning and sentenced to three years in prison, two of which are suspended.

The couple met and married in 2004 and the woman discovered she was HIV-positive during pre-natal testing in 2005. Court evidence showed that her husband was diagnosed in 1994, whilst married to his first wife, but that he was in deep denial of the diagnosis because, according to his defence lawyer, Rafael Pascual

My client is very religious. He prayed for healing. His first wife and the children he had with her never became infected. Therefore he assumed that his prayers were answered. Without ever taking drugs.

Pascual also unsuccesfully argued that the complainant could have been infected by someone else, and that scientific evidence of his responsibility for infection was inconclusive.

The prosecutor had asked for five years in prison, two suspended, but the court gave a more lenient sentence.

Sensoa’s position – and difficulty in reaching marginalised populations – was highlighted in this article in De Standaard (English translation via Google) published last Thursday, the day of the verdict.

Sensoa, the Flemish service and expertise in sexual health, is concerned about the matter in Huy. “We are not asking for criminal prosecutions,” said spokesman Boris Cruyssaert. “In neighboring countries, we see that it is counterproductive. It just makes the taboo, because nobody dares to know if they are infected.”

“That does not mean that HIV patients should not share responsibility [for HIV prevention],” says Cruyssaert. “Only in the case of intentional transmission [should the criminal law be used]. The cultural aspect [of HIV] is often deeply rooted faith. Of course prayer does not eliminate HIV, but the Angolan man is very religious. He was really convinced that his prayers were answered. “

Sensoa tries to reach other cultures, with accessible information [about HIV] but that is not easy. Since 2009, in an opinion by the National Council of the Order of Physicians, a doctor can, in exceptional cases, inform the partner of an HIV patient [if there is a belief of exceptional risk of harm].

The case highlights three important issues.

First, the general law can always be applied even when it appears that a country has so far been spared prosecutions.

Second, people with HIV who have no connection with HIV support services may feel that the criminal law is their only recourse to justice, when appropriate counselling may have mitigated the sense of betrayal felt by the complainant.

Third, cultural issues (including faith-inspired denial) can have a major impact not only on disclosure, but also acccess to treatment, care and support.

Prior to this case, only two individuals had approached Sensoa for legal assistance, and these were civil cases, involving custody issues. In both cases the HIV-positive status of the father was used in court in an attempt to take away the father’s rights.

Two previous attempts at using the criminal courts for HIV exposure or transmission in Belgium were unsuccessful. One involved an HIV-positive man prosecuted for not disclosing to his girlfriend who subsequently tested HIV-positive, and a 2007 case involved an HIV-positive man from Ostend who was prosecuted for attempted murder for not disclosing to his boyfriend, who remained HIV-negative.

US: (Update) Nebraska passes unscientific, stigmatising body fluid assault law

Update: June 7 2011

I’ve just learned via my colleagues at the Positive Justice Project in the US, that The Assault with Bodily Fluids Bill (LB226) introduced into the Nebraska State Legislature by Senator Mike Gloor recently passed into law with no amendments.

For further background on the bill, and Sen. Gloor’s motivation for introducing it, read this excellent piece from Todd Heywood in The Michigan Messenger.

“The entire bill is hinged on gross ignorance about the actual routes and risks of HIV transmission,” says Beirne Roose-Snyder, staff attorney for the Center for HIV Law and Policy in New York City. “Nowhere in the nearly three-decades-long history of the epidemic has a corrections officer been infected by the routes described in the bill. As for serious misinformation, there is real harm caused to law enforcement staff who themselves may be living with HIV, and to those who are not but who are being sold an unsound bill of goods on how to protect themselves, by placing a legislative imprimatur on the unfounded fears about how HIV and other diseases are spread. It also clearly has a negative impact on the way people with HIV are treated in and out of the criminal justice system, and has resulted in people serving decades of time behind bars on the basis of ignorance and hysteria.”

This latest development is extremely disappointing, and suggests that the trend of passing new laws that inappropriately criminalise people with HIV (and, sometimes other blood-borne infections such as hepatitis B or C) in a misguided attempted to protect police or other public safety officers is not reversing.

A similarly unscientific and stigmatising bill – proposing mandatory testing and/or immediate access to medical records of anyone who exposes their bodily fluids to an emergency worker – has recently been proposed in British Columbia, Canada. Read this letter from the BC Civil Liberties Association about why the bill provides a false sense of security and may well be unconstitutional.

Original post: February 1st 2011

This Friday, February 4th, the Nebraska State Legislature will debate The Assault with Bodily Fluids Bill which would criminalise striking any public safety officer with any bodily fluid (or expelling bodily fluids toward them) and includes a specific increase of penalty to a felony (up to five years and/or $10,000 fine) if the defendant is HIV-positive and/or has Hepatitis B or C.

The Bill ignores the fact that HIV cannot be transmitted through spit, urine, vomit, or mucus; punishes the decision to get tested for HIV; and will not keep public safety officers safer, but rather will reinforce misinformation and stigma about HIV.

|

| Download the full text of Nebraska Legislative Bill 226 here |

Two major problems with the Bill are:

1. The proposed language in Sec. 2(3) is contrary to science

- None of the actions criminalised in this Bill pose a real risk of HIV transmission. Spitting while HIV-positive poses no risk of HIV transmission. The Centers for Disease Control has unequivocally stated that spitting cannot transmit HIV. Other “body fluids” identified in the Bill – including mucus, urine, and vomit, absolutely cannot transmit HIV.

2. Codifying the breach of doctor /patient confidentiality in Sec. 2(5) is extremely serious, and should not be undertaken with no public health benefit

- It is extremely important for public and individual health for people with HIV to get tested at the earliest opportunity, start timely treatment, and stay on treatment. This all hinges on having a good relationship with their doctor or health care provider. Forcing doctors and health care providers to reveal private health information, or even testify about it, will have a negative impact on patient trust of the health care system and willingness to remain engaged in HIV care. The plain language in Sec. 2(5) would force any person charged under this statute to be tested for the identified viruses, or force the opening of their medical records for previous testing results.

The Positive Justice Project (PJP) has produced a set of talking points (download here) that summarises the problems with the Bill, and with HIV-specific legislation in general. PJP highlights that the wording of the Bill is so broad that it would allow for the following Kafkaesque situations:

- If a person with HIV accidentally vomits in the direction of a medical officer in a prison infirmary, they could be sentenced to five more years in prison.

- If someone accidentally sneezes in the direction of a police officer, a judge must grant a court order for their medical records and they may be subjected to involuntary HIV antibody and hepatitis B and C antigen testing if the police officer decides to press charges.

- An inmate who spits or vomits in the direction of a corrections officer, even without hitting or intending to hit the officer, can be forcibly tested for HIV and hepatitis and if found to have any of these viruses, charged with a felony.

- An adolescent with HIV or hepatitis held in a juvenile detention facility who spits while being restrained by a corrections officer, or while arguing with a guidance counselor, could wind up serving five years in an adult prison facility.

PJP asks anyone in the United States who cares about this issue to contact their State representative (using the talking points to highlight the many problems with the Bill) and specifically encourages any networks or individuals in Nebraska to contact:

State Senator Mike Gloor, who introduced the Bill.

District 35

Room #1523

P.O. Box 94604

Lincoln, NE 68509

Phone: (402) 471-2617

Email: mgloor@leg.ne.gov

Sandra Klocke

State AIDS Director

Office of Disease Control and Health Promotion

Nebraska Department Health and Human Services

301 Centennial Mall South, 3rd Floor

P.O. Box 95026

Lincoln, Nebraska, 68509-5044

Phone: 402-471-9098-

Fax: 402-471-6446

sandy.klocke@nebraska.gov

and/or

Heather Younger

State Prevention Manager

Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

HIV Prevention

Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services

301 Centennial Mall South

Lincoln, Nebraska, 68509

Phone: 402-471-0362

heather.younger@nebraska.gov