On Wednesday, 26th February, the HIV Justice Network (HJN) co-hosted a parliamentary reception in the UK Parliament in collaboration with the All-Party Parliamentary Group on HIV, AIDS and Sexual Health (APPGA) and the UK’s National AIDS Trust (NAT). The event, held to mark HIV Is Not A Crime Awareness Day, underscored the urgent need to combat HIV criminalisation in an era of rising global anti-rights movements and shrinking HIV funding.

Baroness Barker, Co-Chair of the APPGA, opened the event, acknowledging the significance of addressing HIV criminalisation within the broader context of human rights and public health.

The Global Scale of HIV Criminalisation

HJN’s Executive Director, Edwin J Bernard, was the first speaker, offering insights into the global state of HIV criminalisation, with a particular focus on Commonwealth countries. He highlighted key issues, including:

- HIV criminalisation is state-sponsored stigma It punishes people living with HIV for acts that wouldn’t be crimes if they were HIV-negative, perpetuating discrimination and undermining public health efforts.

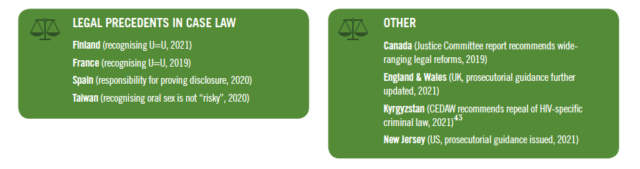

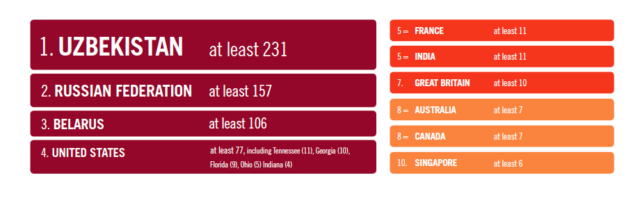

- The scale of injustice is vast At least 80 countries have HIV-specific criminal laws, and prosecutions have taken place in at least 90 countries, with Commonwealth nations lagging in law reform.

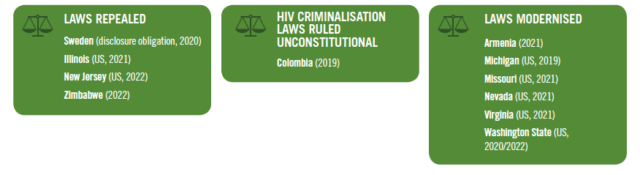

- Progress is happening, but remains under threat While 17 countries have reformed their laws, critical funding cuts jeopardise continued advocacy and reform efforts.

- Sustained investment is essential Law reform takes time, and without long-term, flexible funding, the progress made could be reversed, leaving the most marginalised at risk.

- The time to act is now Policymakers, funders, and advocates must step up to support efforts to end HIV criminalisation and ensure justice for people living with HIV.

Read the full text of his remarks here: HJN Executive Director’s Speech.

Insights from the UK: NAT’s New Report on HIV Criminalisation

Daniel Fluskey, Director of Policy, Research, and Influencing at NAT, presented key findings from NAT’s recently published report, Criminalisation of HIV Transmission: Understanding the Impact (read the report). The report offers several urgent recommendations for reform, including:

- U=U should be central to legal considerations If an individual has an undetectable viral load, no investigation should take place.

- Reckless transmission cases can force disclosure Legal proceedings can place individuals in unsafe situations, potentially exposing them to stigma and harm.

- Police need comprehensive training Investigations must be fair, informed, and necessary to prevent unnecessary criminalisation.

- Voluntary attendance should replace arrest Arrest should not be the default approach when investigating HIV-related cases.

- All stakeholders must receive training Including people living with HIV, support staff, and clinicians, to ensure a more informed legal and healthcare environment.

A Personal Story: The Impact of Criminalisation

The event featured a powerful testimony from a man who was unjustly arrested for a crime that never existed—there was no risk, no harm. As a police officer himself, he never imagined he would experience such a humiliating and disproportionate arrest. Multiple officers arrived at his home and charged him with ‘attempted grievous bodily harm’ without explanation or the chance to respond.

It was only 20 hours into his unlawful detention, during disclosure before his interview, that he was finally told why he had been arrested. At that point, he disclosed his U=U status – evidence that should have prevented his arrest in the first place.

Although he was never formally charged, the case was eventually dismissed as “Entered in Error” after a review of his medical records. Yet, the arrest remains on his record, casting a shadow over his career and deeply impacting his mental health.

“I did nothing wrong,” he concluded, “yet I am still fighting for justice.”

The Forgotten Impact of Past Prosecutions

Sophie Strachan, Director of Sophia Forum, shared her own experience of being diagnosed with HIV while in prison more than two decades ago. She also highlighted the case of the first woman prosecuted in England & Wales for ‘reckless’ HIV transmission. Convicted in 2006 and sentenced to 32 months in prison, she was vilified by the media for a ‘crime’ that would not be prosecuted today under current guidelines.

Nearly 20 years later, this woman remains deeply affected by her conviction. Despite wanting to move forward, her criminal record has made it impossible for her to work or even volunteer. “She is a virtual recluse, terrified that people will still recognise her,” Sophie explained. Her case remains a stark reminder of the lasting impact of unjust prosecutions.

Building Momentum for Change

The reception was attended by members of the UK House of Commons and House of Lords, as well as representatives from UK and international NGOs, philanthropic funders, and advocates working to end HIV criminalisation worldwide.

The discussions reinforced the urgent need for continued advocacy, law reform, and investment to end the unjust criminalisation of people living with HIV. As our Executive Director emphasised: HIV is not a crime. The time to act is now.