The lack of clarity over when a person with HIV has a legal obligation to disclose their HIV-positive status to a sexual partner is resulting in “anxiety, confusion and contradictory HIV counselling advice,” according to a new study on the impact of HIV criminalisation in Canada.

UNAIDS announces new project examining “best available scientific evidence to inform the criminal law”

A new project announced yesterday by UNAIDS will “further investigate current scientific, medical, legal and human rights aspects of the criminalization of HIV transmission. This project aims to ensure that the application, if any, of criminal law to HIV transmission or exposure is appropriately circumscribed by the latest and most relevant scientific evidence and legal principles so as to guarantee justice and protection of public health.”

I’m honoured to be working as a consultant on this project, and although I can’t currently reveal any more details than in the UNAIDS article (full text below), suffice to say it is hoped that this project will make a huge difference to the way that lawmakers, law enforcement and the criminal courts treat people with HIV accused of non-disclosure, alleged exposure and non-intentional transmission.

The UNAIDS article begins by noting some positive developments previously highlighted on my blog, including Denmark’s suspension of its HIV-specific law. It’s not too late to sign on to the civil society letter asking the Danish Government to not to simply rework the law, but to abolish it altogether by avoiding singling out HIV. So far, well over 100 NGOs from around the world have signed the letter.

The article also mentions recent developments in Norway. In fact, the UNAIDS project is funded by the Government of Norway, which has set up its own independent commission to inform the ongoing revision of Section 155 of the Penal Code, which criminalises the wilful or negligent infection or exposure to communicable disease that is hazardous to public health—a law that has only been used to prosecute people who are alleged to have exposed others, to, and/or transmitted, HIV. It will present its findings by October 2012.

As well as highlighting some very positive recent developments in the United States – the National AIDS Strategy’s calls for HIV-specific criminal statutes that “are consistent with current knowledge of HIV transmission and support public health approaches” and the recent endorsement of these calls by the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) – it also focuses on three countries in Africa.

Positive developments have also been reported in Africa. In the past year, at least three countries—Guinea, Togo and Senegal—have revised their existing HIV-related legislation or adopted new legislation that restrict the use of the criminal law to exceptional cases of intentional transmission of HIV.

I’d like to add a few more countries to the “positive development” list.

Canada

Last September, I spoke at two meetings, in Ottawa and Toronto, that officially launched the Ontario Working Group on Criminal Law and HIV Exposure’s Campaign for Prosecutorial Guidelines for HIV Non-disclosure.

The Campaign’s rationale is as follows

We believe that the use of criminal law in cases of HIV non-disclosure must be compatible with broader scientific, medical, public health, and community efforts to prevent the spread of HIV and to provide care treatment and support to people living with HIV. While criminal prosecutions may be warranted in some circumstances, we view the current expansive use of criminal law with concern.

We therefore call on Ontario’s Attorney General to immediately undertake a process to develop guidelines for criminal prosecutors in cases involving allegations of non-disclosure of HIV status.

Guidelines are needed to ensure that HIV-related criminal complaints are handled in a fair and non-discriminatory manner. The guidelines must ensure that decisions to investigate and prosecute such cases are informed by a complete and accurate understanding of current medical and scientific research about HIV and take into account the social contexts of living with HIV.

We call on Ontario’s Attorney General to ensure that people living with HIV, communities affected by HIV, legal, public health and scientific experts, health care providers, and AIDS service organizations are meaningfully involved in the process to develop such guidelines.

Last month, Xtra.ca reported that

The office of the attorney general confirms it is drafting guidelines for cases of HIV-positive people who have sex without disclosing their status.

This is a major breakthrough, but the campaign still needs your support. Sign their petition here.

By the way, video of the Toronto meeting, ‘Limiting the Law: Silence, Sex and Science’, is now online.

Australia

Also last month, the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations (AFAO) produced an excellent discussion paper/advocacy kit, ‘HIV, Crime and the Law in Australia: Options for Policy Reform‘.

As well as providing an extensive and detailed overview regarding the current (and past) use of criminal and public health laws in its eight states and territories, it also provides the latest data on number, scope and demographics of prosecutions in Australia.

There have been 31 prosecutions related to HIV exposure or transmission in Australia over almost twenty years. Of those, a number have been dropped pre-trial, and in four cases the accused has pleaded guilty. All those charged were male, except for one of two sex workers (against whom charges were dropped pretrial in 1991). In cases where the gender of the victim(s) is/are known, 16 have involved the accused having sex with female persons (one of those cases involves assault against minors) and 10 involved the accused having sex with men. This suggests that heterosexual men, who constitute only about 15% of people diagnosed with HIV, are over-represented among the small number of people charged with offences relating to HIV transmission. Further, men of African origin are over-represented among those prosecuted (7 of 30), given the small size of the African-Australian community.

It then systematically examines, in great detail, the impact of such prosections in Australia.

These include:

- HIV-related prosecutions negate public health mutual responsibility messages

- HIV-related prosecutions fail to fully consider the intersection of risk and harm

- HIV-related prosecutions ignore the reality that failure to disclose HIVstatus is not extraordinary

- HIV-related prosecutions reduce trust in healthcare practitioners

- HIV-related prosecutions increase stigma against people living with HIV

- HIV-related prosecutions are unacceptably arbitrary

- HIV-related prosecutions do not decrease HIV transmission risks

- HIV-related prosecutions that result in custodial sentences increase the population of HIV-positive people in custodial settings

It notes, however, that

There is a narrow category of circumstances in which prosecutions may be warranted, involving deliberate and malicious conduct, where a person with knowledge of their HIVstatus engages in deceptive conduct that leads to HIV being transmitted to a sexual partner. A strong, cohesive HIV response need not preclude HIV-related prosecutions per se. Further work is required by those working in the areas of HIV and of criminal law:

- To consider what circumstances of HIV transmission should be defined as criminal;

- To define what measures need to be put in place to ensure that prosecutions are a last resort option and that public health management options have been considered; and

- To ensure those understandings are part of an ongoing dialogue that informs the development of an appropriate criminal law and public health response.

That’s exactly the kind of policy outcome that UNAIDS is hoping for.

In the meantime, AFAO suggests some possible strategies towards policy reform. Their recommendations make an excellent advocacy roadmap for anyone working to end the inappropriate use of the criminal law.

Their suggestions include:

- Enable detailed discussion and policy development

- Develop mechanisms to learn more about individual cases

- Prioritise research on the intersection of public health and criminal law mechanism, including addressing over-representation of African-born accused

- Work with police, justice agencies, state-based agencies and public health officials

- Improve judges’ understanding of HIV and work with expert witnesses

- Work with correctional authorities

- Work with media

I truly hope that the recent gains by advocates in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Guinea, Norway, Togo, Senegal and the United States is the beginning of the end of the overly broad use of the criminal law to inappropriately regulate, control, criminalise and stigmatise people with HIV in the name of justice or public health.

The full UNAIDS article is below. I’ll update you on the project’s progress just as soon as I can.

Countries questioning laws that criminalize HIV transmission and exposure

26 April 2011

On 17 February 2011, Denmark’s Minister of Justice announced the suspension of Article 252 of the Danish Criminal Code. This law is reportedly the only HIV-specific criminal law provision in Western Europe and has been used to prosecute some 18 individuals.

A working group has been established by the Danish government to consider whether the law should be revised or abolished based on the best available scientific evidence relating to HIV and its transmission.

This development in Denmark is not an exception. Last year, a similar official committee was created in Norway to inform the ongoing revision of Section 155 of the Penal Code, which criminalises the wilful or negligent infection or exposure to communicable disease that is hazardous to public health—a law that has only been used to prosecute people transmitting HIV.

In the United States, the country with the highest total number of reported prosecutions for HIV transmission or exposure, the National AIDS Strategy adopted in July 2010 also raised concerns about HIV-specific laws that criminalize HIV transmission or exposure. Some 34 states and 2 territories in the US have such laws. They have resulted in high prison sentences for HIV-positive people being convicted of “exposing” someone to HIV after spitting on or biting them, two forms of behaviour that carry virtually no risk of transmission.

In February 2011, the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD), the organization representing public health officials that administer state and territorial HIV programmes, expressed concerns about the “corrosive impact” of overly-broad laws criminalizing HIV transmission and exposure. The AIDS Directors called for the repeal of laws that are not “grounded in public health science” as such laws discourage people from getting tested for HIV and accessing treatment.

Positive developments have also been reported in Africa. In the past year, at least three countries—Guinea, Togo and Senegal—have revised their existing HIV-related legislation or adopted new legislation that restrict the use of the criminal law to exceptional cases of intentional transmission of HIV.

Best available scientific evidence to inform the criminal lawThese developments indicate that governments are also calling for a better understanding of risk, harm and proof in relation to HIV transmission, particularly in light of scientific and medical evidence that the infectiousness of people receiving anti-retroviral treatment can be significantly reduced.

To assist countries in the just application of criminal law in the context of HIV, UNAIDS has initiated a project to further investigate current scientific, medical, legal and human rights aspects of the criminalization of HIV transmission. This project aims to ensure that the application, if any, of criminal law to HIV transmission or exposure is appropriately circumscribed by the latest and most relevant scientific evidence and legal principles so as to guarantee justice and protection of public health. The project, with support from the Government of Norway, will focus on high income countries where the highest number of prosecutions for HIV infection or exposure has been reported.

The initiative will consist of two expert meetings to review scientific, medical, legal and human rights issues related to the criminalization of HIV transmission or exposure. An international consultation on the criminalization of HIV transmission and exposure in high income countries will also be organized.

The project will further elaborate on the principles set forth in the Policy brief on the criminalization of HIV transmission issued by UNAIDS and UNDP in 2008. Its findings will be submitted to the UNDP-led Global Commission on HIV and the Law, which was launched by UNDP and UNAIDS in June 2010.

As with any law reform related to HIV, UNAIDS urges governments to engage in reform initiatives which ensure the involvement of all those affected by such laws, including people living with HIV.

Edwin J Bernard’s Keynote at Funders Concerned About AIDS: ‘Combating HIV Criminalization at Home & Abroad’ (2010)

Edwin J Bernard’s keynote presentation at the Funders Concerned About AIDS 2010 Philanthropy Summit, Washington DC, December 6 2010.

The slides for this presentation are available to donwload (as a pdf) here: bit.ly/fcaadec10

US: Positive Justice Project publishes essential new advocacy resource

The Center for HIV Law and Policy has released the first comprehensive analysis of HIV-specific criminal laws and prosecutions in the United States. The publication, Ending and Defending Against HIV Criminalization: State and Federal Laws and Prosecutions, covers policies and cases in all fifty states, the military, federal prisons and U.S. territories.

Ending and Defending Against HIV Criminalization: State and Federal Laws and Prosecutions is intended as a resource for lawyers and community advocates on the laws, cases, and trends that define HIV criminalization in the United States. Thirty-four states and two U.S. territories have HIV-specific criminal statutes and thirty-six states have reported proceedings in which HIV-positive people have been arrested and/or prosecuted for consensual sex, biting, and spitting. At least eighty such prosecutions have occurred in the last two years alone.

People are being imprisoned for decades, and in many cases have to register as sex offenders, as a consequence of exaggerated fears about HIV. Most of these cases involve consensual sex or conduct such as spitting and biting that has only a remote possibility of HIV exposure. For example, a number of states have laws that make it a felony for someone who has had a positive HIV test to spit on or touch another person with blood or saliva. Some examples of recent prosecutions discussed in CHLP’s manual include:

• A man with HIV in Texas is serving thirty-five years for spitting at a police officer;

• A man with HIV in Iowa, who had an undetectable viral load, received a twenty-five year sentence after a one-time sexual encounter during which he used a condom; his sentence was suspended, but he had to register as a sex-offender and is not allowed unsupervised contact with his nieces, nephews and other young children;

• A woman with HIV in Georgia received an eight-year sentence for failing to disclose her HIV status, despite the trial testimony of two witnesses that her sexual partner was aware of her HIV positive status;

• A man with HIV in Michigan was charged under the state’s anti-terrorism statute with possession of a “biological weapon” after he allegedly bit his neighbor.

The catalog of state and federal laws and cases is the first volume of a multi-part manual that CHLP’s Positive Justice Project is developing for legal and community advocates. The goal of the Positive Justice Project is to bring an end to laws and policies that subject people with HIV to arrest and increased punishment on the basis of gross ignorance about the nature and transmission of HIV, without consideration of the actual risks of HIV exposure.

The manual’s completion was supported by grants for CHLP’s anti-criminalization work and Positive Justice Project from the MAC AIDS Fund and Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS.

Download the manual here (2.3MB)

US: Majority of gay US men support criminal non-disclosure laws

The overwhelming majority (70%) of HIV-negative and untested men (69%) in the United States support prosecutions for not disclosing known HIV-positive status before sex that may risk HIV transmission, according to a new study by Keith J. Horvatha, Richard Weinmeyera and Simon Rosser at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Even more disturbing is the fact 38% of HIV-positive men endorsed criminalisation.

The most worrying finding is that suppport of non-disclosure laws strongly suggested a reliance on disclosure as an HIV prevention method. As I have discussed in HIV and the criminal law, this is unreliable and problematic.

There’s a summary of the study’s findings at aidsmap.com and the full text article can be downloaded here.

Canada: New report calls for prosecutorial guidelines to establish ‘significant risk’

A new report, launched at AIDS 2010 in Vienna last month, recommends that the Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General establish a consultation process to inform the development of prosecution guidelines for cases involving allegations of non-disclosure of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

HIV Non-Disclosure and the Criminal Law: Establishing Policy Options for Ontario contributes to the development of an evidence-informed approach to using the criminal law to address the risk of the sexual transmission of HIV infection in Ontario, and offers the most comprehensive, current discussion of the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure in Canada.

The report was triggered by the absence of policy-based discussion of this issue amongst key decision makers in government and by community concerns about the intensified use and wide reach of the criminal law in circumstances of HIV non-disclosure.

In Canada, people living with HIV have a criminal law obligation to disclose their status before engaging in activities that pose a “significant risk” of HIV transmission. The report emphasises that uncertainties associated with that obligation and interpretations of the obligation that are not informed by current scientific research on HIV transmission risks are foundational to current problems in the use of the criminal law to regulate the risk of the sexual transmission of HIV and explores various forms of evidence relevant to a thorough policy consideration of the use of the criminal law in situations of HIV non-disclosure in sexual relationships.

York University has produced a 1200 word pdf summary of the report which I’m including in its entirety below. A pdf of the entire report can be downloaded here.

Title: The criminal law about sex and HIV disclosure is not clear

What is this research about?

According to the Supreme Court of Canada, HIV-positive people are required to disclose their status before engaging in sexual activities that pose a “significant risk” of transmitting HIV to a sex partner. Canadian courts, however, have yet to clearly define what sex acts, in what circumstances, carry a “significant risk.” This has led to an expansive use of the criminal law and created a problem for people with HIV—they can face criminal charges even though the law is not clear about when they must tell sex partners about their HIV. For example, people with HIV who are taking anti-HIV medications are much less likely to transmit HIV during sex, even where no condoms are used. But Ontario police and Crown Attorneys continue to interpret “significant risk” broadly. In fact, charges have been pursued in cases where, on a scientific level, there is little risk of HIV transmission.

This uncertainty has created problems not only for people with HIV but also for public health staff, and health care and social service providers. It has challenged these front-line workers in their attempts to counsel and support people with HIV. It has also caused many people with HIV to be further stigmatized. The media, in its coverage of these cases, has tended to exaggerate the risk of HIV transmission at a time when more and more experts have come to think of HIV as a chronic and manageable infection.

Despite these problems, and over 100 criminal cases in Canada, there has been a lack of evidence to inform public discussion about this important criminal justice policy issue. In Ontario, policy-makers have not weighed in publicly on the criminalization of people who do not reveal to their sex partners that they have HIV.

What did the researchers do?

A project team, led by Eric Mykhalovskiy, Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at York University, set out to explore how the criminal law has been used in prosecutions involving allegations of HIV non-disclosure. The team included members of community organizations in Toronto and front-line workers, some of whom are living with HIV. Their goal was to create evidence and propose options to guide policy and law reform. They created the first national database on criminal cases of HIV non-disclosure in Canada. Professor Mykhalovskiy interviewed over 50 people with HIV, public health staff, and health care and social service providers to find out how the criminal law is affecting their lives or their work—another Canadian first.

What did the researchers find?

From 1989 to 2009, Canada saw 104 criminal cases in which 98 people were charged for not disclosing to sex partners that they have HIV. Ontario accounts for nearly half of these cases. Most of the cases have occurred since 2004. Half of the heterosexual men who have been charged in Ontario since 2004 are Black. Nearly 70% of all cases have resulted in prison terms. In 34% of these cases, HIV transmission did not occur.

Looking at the cases in Ontario and Canada, the researchers found inconsistencies in the evidence courts relied on to decide whether a sex act carried a significant risk of HIV transmission. They also found inconsistencies in how courts have interpreted the legal test established by the Supreme Court, and inconsistencies between court decisions in cases with similar facts. It appears, in some cases, that police and Crown prosecutors have not been guided by the scientific research when deciding whether to lay charges or proceed with a prosecution.

Because it is important to understand the scientific research when assessing whether there is a “significant risk” of HIV transmission during sex, the researchers included in their report a succinct summary of the leading science. The risk, in general, is low. Activities like unprotected sexual intercourse carry a risk that is much lower than commonly believed. Most unprotected intercourse involving an HIV-positive person does not result in the transmission of HIV. But the risk of transmission is not the same for all sex acts and circumstances. Antiretroviral therapy, however, can reduce the amount of HIV in a person’s bloodstream and make the person less infectious to their partner. Also, because of antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection has gone from being a terminal disease to a chronic, manageable condition in the eyes of many experts and people living with the virus.

Many people with HIV who were interviewed remain concerned that even if they disclose their HIV, their sex partners might complain to police. Health care and service providers stated that they are confused by the vagueness of the law. They also stated that criminalizing HIV non-disclosure prevents people from seeking the support they need to come to grips with living with HIV and disclosing to partners. But people with HIV and their providers have many suggestions for improving public policy and the law. The “significant risk” test needs to be clarified. The public health and criminal justice systems need to work together. And policies and procedures to guide Crown Attorneys need to be put in place.

How can you use this research?

Policymakers have several options to respond to the lack of clarity in the law and the resulting expansive use of the law. They can continue to let police, Crown Attorneys, and courts deal with cases as they arise. They can work to amend the Criminal Code. But the best solution, in the short term, would be the development of policy and procedures to guide Crown Attorneys working on these types of cases. The Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General should establish a consultation process to help develop policy and procedures for criminal cases in which people have allegedly not disclosed that they are HIV-positive to their sex partners.

What you need to know:

The criminal law can lead to very serious consequences for people who are charged or convicted. So policymakers need to make sure that the criminal law about HIV disclosure is clear and clearly informed by scientific research about HIV transmission. They also need to look to research to assess whether the law is having unintended consequences that get in the way of HIV prevention efforts.

About the Researchers:

Eric Mykhalovskiy is an Associate Professor and CIHR New Investigator in the Department of Sociology. Glenn Betteridge is a former lawyer who now works as a legal and health consultant. David McLay holds a PhD in biology and is a professional science writer.

This Research Snapshot is from their report, “HIV Non-disclosure and the criminal law: Establishing policy options for Ontario,” which was funded by the Ontario HIV Treatment Network and involved a research collaboration between York University, Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, HIV and AIDS Legal Clinic (Ontario), Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention, AIDS Committee of Toronto, and Toronto PWA Foundation.

Global: AIDS 2010 round-up part 2: Posters

This selection of posters presented in Vienna follows up from my previous AIDS 2010 posting on the sessions, meetings and media reporting that took place during last month’s XVIII International AIDS Conference. I’ll be a highlighting a few others in later blog posts, but for now here’s three posters that highlight how the law discriminates; why non-disclosure is problematic to criminalise; and how political advocacy can sometimes yield positive change.

In Who gets prosecuted? A review of HIV transmission and exposure cases in Austria, England, Sweden and Switzerland, (THPE1012) Robert James examines which people and which communicable diseases came to the attention of the criminal justice system in four European countries, and concludes: “Men were more likely than women to be prosecuted for HIV exposure or transmission under criminal laws in Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. The majority of cases in Austria involved the prosecution of female sex workers. Migrants from southern and west African countries were the first people prosecuted in Sweden and England but home nationals have now become the largest group prosecuted in both countries. Even in countries without HIV specific criminal laws, people with HIV have been prosecuted more often than people with more common contagious diseases.”Download the pdf here.

In Responsibilities, Significant Risks and Legal Repercussions: Interviews with gay men as complex knowledge-exchange sites for scientific and legal information about HIV (THPE1015), Daniel Grace and Josephine MacIntosh from Canada interviewed 55 gay men, some of whom were living with HIV, to explore issues related to the criminalisation of non-disclosure, notably responsibilities, significant risks and legal repercussions. Their findings highlight why gay men believe that disclosure is both important and highly problematic. Download the pdf here.

In Decriminalisation of HIV transmission in Switzerland (THPE1017), Luciano Ruggia and Kurt Pärli of the Swiss National AIDS Commission (EKAF) – the Swiss statement people – describe how they have been working behind the scenes to modify Article 231 of the Swiss Penal Code which allows for the prosecution by the police of anyone who allegedly spreads “intentionally or by neglect a dangerous transmissible human disease” without the need of a complainant. Disclosure of HIV-positive status and/or consent to unprotected sex does not preclude this being an offence, in effect criminalising all unprotected sex by people with HIV. Since 1989, there have been 39 prosecutions and 26 convictions under this law. A new Law on Epidemics removes Article 231, leaving only intentional transmission as a criminal offence, and will be deabted before the Swiss Parliament next year. Download the pdf here.

Global: AIDS 2010 round-up part 1: sessions, meetings and media reports

A remarkable amount of advocacy and information sharing took place during the XVIII International AIDS Conference held in Vienna last month. Over the next few blog posts, I’ll be highlighting as much as I can starting with a round-up of sessions, meetings, and media reports from the conference. A separate blog post will highlight posters, a movie screening and some inspirational personal meetings.

Sunday: Criminalisation of HIV Exposure and Transmission: Global Extent, Impact and The Way Forward

A meeting that I co-organised (representing NAM) along with the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+) and the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network received quite a lot of coverage.

Criminalisation of HIV Exposure and Transmission: Global Extent, Impact and The Way Forward was a great success with many of the 80+ attendees telling me it was Vienna highlight. The entire meeting, lasting around 2 1/2 hours, has been split into eight videos: an introduction; six presentations; and an audience and panel discussion. The entire meeting can also be viewed at the NAM and Legal Network websites, with GNP+ soon to follow.

Reports from the meeting focusing on different parts of the meeting were filed by NAM and NAPWA (Aus) and I was interviewed by Mark S King for his video blog for thebody.com.

Richard Elliott of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, Moono Nyambe from GNP+ and UNAIDS’ Susan Timberlake – all of whom took part in the meeting – were interviewed for a piece in Canada’s Globe and Mail, with the headline, U.S., Canada lead world in prosecuting those who transmit AIDS virus: Criminal charges are justified only when infection is intentional, activists contend.

The same day, an editorial in the Globe and Mail completely undermined the rather balanced article by stating, quite bluntly

Disclosing one’s status is, of course, a difficult and emotional journey, fraught with potentially negative consequences. HIV-positive people can be marginalized, and discriminated against in terms of housing, employment and social relationships. However, the collective rights of this minority group cannot take precedence over their individual responsibility not to infect others.

It concluded

But in Canada the law is clear: Exposure without disclosure is a crime. And that is a good thing.

Judging by the comments left by readers of both articles, although there is some sympathy for the person with HIV, there’s a long way to go before Canadian hearts and minds are won over by the anti-criminalisation advocacy movement.

Wednesday: Policing Sex and Sexuality: The Role of Law in HIV

Lucy Stackpool-Moore (IPPF) and Mandeep Dhaliwal (UNDP)co-chaired a satellite session on the Wednesday that included presentations by Anand Grover, UN Special Rapporteur on Right to Health, and my colleague Robert James of Birkbeck College, University of London.

Thursday: HIV and Criminal Law: Prevention or Punishment?

This debate included discussion of criminalisation from the point of view of increased stigma. Lucy Stackpool-Moore again contributed. The session was not only recorded by the rapporteur, Skhumbuzo Maphumulo, but also reported on by PLUS News.

Thursday: Leaders against Criminalization of Sex Work, Sodomy, Drug Use or Possession, and HIV Transmission

I’ve already included a blog posting on my presentation, which you can see here. The other presentations included Criminalization of HIV transmission and exposure and obligatory testing in 8 Latin American countries, presented by Tamil Rainanne Kendall. (Audio and slides here); Tanzania case study on how AIDS law criminalizes stigma and discrimination but also stigmatizes by criminalizing deliberate HIV infection, presented by Millicent Obaso (Audio and slides here); and If there is no risk and no harm there should be no crime. Legal, evidential and procedural approaches to reducing unwarranted prosecutions of people with HIV for exposure and transmission, presented by Robert James (and co-authored by yours truly). (Audio and slides here).

The session was also reported on by aidsmap.com.

Thursday: Late Breakers (Track F)

This session included three oral abstracts on criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission.

A quantitative study of the impact of a US state criminal HIV disclosure law on state residents living with HIV, presented by Carol Galletly. (Audio and slides here).

Roger Pebody of aidsmap.com provides an excellent summary of her findings here

Under [Michigan] state legislation, people with HIV are legally obliged to disclose their HIV status before any kind of sexual contact. Disclosure is meant to occur before sexual intercourse “or any other intrusion, however slight, of any part of a person’s body or of any object into the genital or anal openings of another person’s body”. This would include even fingering or the use of a sex toy.

Carol Galletly reported on a study with 384 people with HIV who live in Michigan (but recruitment methods and demographics were not fully described). Three quarters of respondents were aware of the law.

She wanted to see if the existence of the law had any impact on her respondents’ behaviour. Comparing those who were aware of the law with those who were not, people who knew about the law were no more likely to disclose their HIV status to sexual partners. Moreover they were not less likely to have risky sex.

On the other hand, approximately half of participants believed that the law made it more likely that people with HIV would disclose to sex partners. Having this belief was associated with being a person who did disclose HIV status to partners.

In fact a majority of participants supported the law. Individuals who Gallety characterised as possibly being marginalised were more likely to support the law: women, non-whites, people with less education and people with a lower income.

The two other presentations were: HIV non-disclosure and the criminal law: effects of Canada’s ‘significant risk’ test on people living with HIV/AIDS and health and social service providers, presented by Eric Mykhalovskiy (Audio and slides here) and Advocating prevention over punishment: the risks of HIV criminalization in Burkina Faso presented by Patrice Sanon (Audio and slides here).

Other media reports

Other reports mentioning the criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission published during the conference include:

A piece in the Montreal Gazette, headlined, Advocates raise concerns over prosecuting HIV-positive people

The troubling increase in the number of new HIV cases in Canada may be attributed to the country’s reputation of being a world leader in prosecuting HIV-positive people who fail to disclose their status, according to one group of AIDS advocates. “We’re looking at rising numbers of infection, especially among certain risk groups,” said Ron Rosenes, vice chair of Canadian Treatment Action Council. “And now we’re looking at the criminalization issue as one of the reasons people have been afraid to learn their status.”

Global: ‘Where HIV is a crime, not just a virus’ – updated Top 20 table and video presentation now online

Where HIV Is a Crime, Not Just a Virus from HIV Action on Vimeo.

Here is my presentation providing a global overview of laws and prosecutions at the XVIII International AIDS Conference, Vienna, on 22 July 2010.

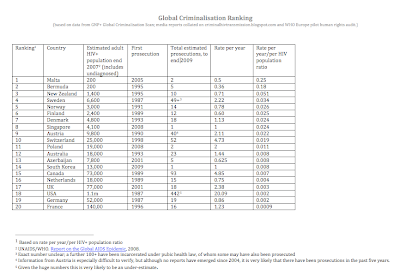

Abstract: Where HIV is a crime, not just a virus: a global ranking of prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

Issues: The global (mis)use of the criminal law to control and punish the behaviour of PLHIV was highlighted at AIDS 2008, where Justice Edwin Cameron called for “a campaign against criminalisation”. However advocacy on this vitally important issue is in its infancy, hampered by lack of information on a local, national and international level.

Description: A global overview of prosecutions to December 2009, based on data from GNP+ Global Criminalisation Scan (http://criminalisation.gnpplus.net); media reports collated on criminalhivtransmission.blogspot.com and WHO Europe pilot human rights audit. Top 20 ranking is based on the ratio of rate per year/per HIV population.

Lessons learned: Prosecutions for non-intentional HIV exposure and transmission continue unabated. More than 60 countries have prosecuted HIV exposure or transmission and/or have HIV-specific laws that allow for prosecutions. At least eight countries enacted new HIV-specific laws in 2008/9; new laws are proposed in 15 countries or jurisdictions; 23 countries actively prosecuted PLHIV in 2008/9.

Next steps: PLHIV networks and civil society, in partnership with public sector, donor, multilateral and UN agencies, must invest in understanding the drivers and impact of criminalisation, and work pragmatically with criminal justice system/lawmakers to reduce its harm.

Video produced by www.georgetownmedia.de

|

| This table reflects amended data for Sweden provided by Andreas Berglöf of HIV Sweden after the conference, relegating Sweden from 3rd to 4th. Its laws, including the forced disclosure of HIV-positive status, remain some of the most draconian in the world. Click here to download pdf. |

Edwin J Bernard: Where HIV Is a Crime, Not Just a Virus (AIDS 2010)

Edwin J Bernard presents a global overview of laws and prosecutions at the XVIII International AIDS Conference, Vienna, 22 July 2010.

Abstract: Where HIV is a crime, not just a virus: a global ranking of prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

Issues: The global (mis)use of the criminal law to control and punish the behaviour of PLHIV was highlighted at AIDS 2008, where Justice Edwin Cameron called for “a campaign against criminalisation”. However advocacy on this vitally important issue is in its infancy, hampered by lack of information on a local, national and international level.

Description: A global overview of prosecutions to December 2009, based on data from GNP+ Global Criminalisation Scan (criminalisation.gnpplus.net); media reports collated on criminalhivtransmission.blogspot.com and WHO Europe pilot human rights audit. Top 20 ranking is based on the ratio of rate per year/per HIV population.

Lessons learned: Prosecutions for non-intentional HIV exposure and transmission continue unabated. More than 60 countries have prosecuted HIV exposure or transmission and/or have HIV-specific laws that allow for prosecutions. At least eight countries enacted new HIV-specific laws in 2008/9; new laws are proposed in 15 countries or jurisdictions; 23 countries actively prosecuted PLHIV in 2008/9.

Next steps: PLHIV networks and civil society, in partnership with public sector, donor, multilateral and UN agencies, must invest in understanding the drivers and impact of criminalisation, and work pragmatically with criminal justice system/lawmakers to reduce its harm.

Video produced by georgetownmedia.de