- Repeal and reform of laws criminalizing HIV exposure, non-disclosure and transmission

- An end to law enforcement practices that target communities disproportionately impacted by HIV, including people of trans and gender nonconforming experience (TGNC), sex workers, people who use drugs, immigrants, people who are unstably housed, people with mental illness, and communities of color

- An end to stigmatizing and discriminatory interactions, methods of surveillance and brutalization of PLHIV and communities impacted by HIV at the hands of law enforcement

- Elimination of barriers to safe, stable, and meaningful reintegration into the community for those returning home from jail and prison, those with criminal convictions, and the loved ones who support them.

Mexico: Quintana Roo activists submit proposal for a change in the State HIV criminalisation law

Submission to eliminate the criminalisation of people with HIV (Desplácese hacia abajo para el artículo original)

This initiative has been proposed by the organisation ‘Vida Positiva’.

PLAYA DEL CARMEN, Q. Roo

A proposition to eliminate the criminalization and general criminalization of people with HIV having sex, focussing on cases of willful intent by amending Article 113 of the Criminal Code of Quintana Roo, is being put forward.

This initiative has been proposed by the civil association ‘Vida Positiva’ and delivered to deputy Laura Beristain Navarrete, president of the Commission for Health and Social Welfare of the XV Legislature to be adapted and submitted to the State Congress at the beginning of October.

Rudolf Geers, president of the activist group said that its aims are for the legislation mentioned to be replaced by a new article which sanction the transmission of a chronic or fatal disease deceitfully and when protection methods have not been used.

“What we propose is that the law be changed to only prosecute cases of actual transmission, removing talks of risks, and cases where there was actual deception and where people did not use protection, in order to qualify the intent of the situation. In the case of pregnant women, to only prosecute cases where the mother had the express intention of infecting the baby. There was one prosecution in January this year, “said the leader of Vida Positiva.

On this matter, Deputy Beristain Navarrete said it was an issue that will be analyzed in a responsible manner, which will be reviewed properly to be subsequently pass on to the committee because every project must be adapted for proper submission, especially when concerning such a sensitive issue as health risks.

Background information

Meanwhile, Geers highlighted that looking at the history of the law, this Article has only served to motivate cases of blackmail and extortion, which have threatened to expose people because of their HIV status, even without evidence, and even when cases did not proceed, the name of the person with the condition had been made public.

“This year, we have had reports of four cases and the advice was to ignore them and just 3 years ago, a lawsuit under this law was recorded. Furthermore this legislation is based on a federal law adopted in 1991; a time when it was a deadly disease with no treatment; It also violates several national and international standards and is counterproductive to an effective response to HIV.

According to CENSIDA, this measure was taken internationally, including in Mexico since the last decade of the last century as a preventive measure against transmission or as a punishment of behaviours that are perceived as ‘willful’, however, we can state that this has not worked with punitive measures, and without public health policies.

“We need to increase resources and efforts with recommended HIV prevention strategies, improve the quality and comprehensiveness of care and reduce stigma and discrimination towards key populations and people living with HIV and other STIs, considering them as part of the solution and contributiors to a fair, inclusive and democratic Mexico”, stated the National Center for the Prevention and Control of HIV and AIDS on the criminalisation of HIV and other STIs transmission.

Rudolf Geers, president of the civil association Vida Positiva stressed that in these cases the responsibility to prevent further transmission is shared; anyone who has casual sex should use a condom.

—————————————————————————

Proponen eliminar la criminalización de las personas con VIH

Esta iniciativa ha sido propuesta por la asociación civil ‘Vida Positiva’.

PLAYA DEL CARMEN, Q. Roo.- Proponen eliminar la criminalización y la penalización general de las personas con VIH por tener relaciones sexuales, especificando casos de intencionalidad consumada, mediante la modificación del artículo 113 del Código Penal de Quintana Roo.

Esta iniciativa ha sido propuesta por la asociación civil ‘Vida Positiva’ y entregada a la diputada Laura Beristaín Navarrete, presidenta de la Comisión de Salud y Asistencia Social de la XV Legislatura para su adecuación y presentación ante el Congreso del Estado a inicios del mes de octubre.

Rudolf Geers, presidente de dicha agrupación activista explicó que se tiene como objetivo que dicha legislación se sustituya por un nuevo artículo el cual sancione una transmisión de una condición de salud crónica o mortal con engaño y sin usar métodos de protección.

“Lo que nosotros proponemos que se cambie esta ley para que solo se castigue en caso de existir una transmisión, quitar la palabra peligro, castigando los casos en que hubo engaño y que no usaron protección, para poder calificar la intencionalidad de la situación. En el caso de la mujer embarazada, solo cuando la madre tiene la intención expresa de infectar al bebé sea castigado. De estos tuvimos un caso en enero de este año”, dijo el dirigente de Vida Positiva A.C.

Antecedentes registrados

Al respecto la diputada Beristain Navarrete señaló que es un tema que se estará analizando de manera responsable, que se revisará de manera adecuada para posteriormente pasarla a comisión, ya que todo proyecto hay que adecuarlo para su correcta presentación, en especial un tema delicado en referencia a riesgos sanitarios.

Por su parte, Geers aseguro que de acuerdo a los antecedentes registrados, este artículo solo ha servido para motivar casos de chantajes y extorsiones, que han amenazado con exponer a personas por su condición de VIH, incluso sin pruebas y aunque posteriormente no proceda la demanda, pero si haciendo público el nombre de la persona con este padecimiento.

“De estos hemos tenido este año reportes de cuatro casos y el consejo simplemente fue ignorarlos y hace 3 años se registró un caso de una demanda por esta ley. Además esta legislación, está basada en una federal de 1991; época en que era un padecimiento mortal al no haber tratamiento; además viola varias normas nacionales e internacionales y es contraproducente para una respuesta eficiente ante el VIH.

De acuerdo a CENSIDA, esta medida había sido tomada a nivel internacional, incluyendo a México desde la última década del siglo pasado como una medida de prevención de transmisión o castigo de conductas que se perciben como ’dolosas’, sin embargo, aseguran que esto no tendrpa éxito con medidas punitivas si no políticas de salud públicas.

Prevención y control

“Es necesario incrementar recursos y esfuerzos en las estrategias recomendadas para prevenir la transmisión del VIH, mejorar la calidad y la integralidad de la atención y disminuir el estigma y la discriminación hacia las poblaciones clave y las personas afectadas por el VIH y otras ITS, considerándolas como parte de la solución y contribuyendo a un México justo, incluyente y democrático”, señala sobre la penalización por transmisión del VIH y otras ITS en Centro Nacional para la Prevención y Control del VIH y el Sida.

Rudolf Geers, presidente de la asociación civil Vida Positiva enfatizó que en estos casos la responsabilidad para evitar nuevas transmisiones es compartida; cualquier persona que tenga relaciones sexuales casuales sebe de usar condón.

US: New report explores how HIV criminal laws in California are enforced against foreign born populations

FOR IMMIGRANTS, HIV CRIMINALIZATION CAN MEAN INCARCERATION AND DEPORTATION

New Study Shows 15 Percent of People who had Contact with Californa Criminal System because of HIV Criminalization Laws were Foreign Born

LOS ANGELES – A new study suggests that for some immigrants, an HIV-specific criminal offense may have been the triggering event for their deportation proceedings. In HIV Criminalization Against Immigrants in California, Williams Institute Scholars Amira Hasenbush and Bianca D.M. Wilson, explore how HIV criminal laws are enforced in California, particularly against foreign born populations.

HIV criminalization is a term used to describe statutes that either criminalize otherwise legal conduct or that increase the penalties for illegal conduct based upon a person’s HIV-positive status. California has four HIV-specific criminal laws, and one non-HIV-specific criminal law that criminalizes exposure to any communicable disease. All HIV-specific offenses in California have the potential to lead to deportation proceedings.

“People living with HIV still face stigma and discrimination,” said Amira Hasenbush. “If one is HIV-positive and enters the criminal system, one may be more severely impacted than those who are HIV-negative. A major impact for HIV positive immigrants is possible deportation, possibly a far worse outcome than the original sentence. Living with HIV is a public health matter, not a criminal one.”

Key Findings:

-Overall, 800 people have come into contact with the California criminal system from 1988 to June 2014 related to that person’s HIV-positive status. Among those individuals, 121 (15 percent) were foreign born.

-Thirty-six people, or 30 percent, of these foreign born individuals, had some form of a criminal immigration proceeding in their histories. Among those who had immigration proceedings in their records, nine people (25 percent) had those proceedings initiated immediately after an HIV-specific incident.

-Like their U.S. born counterparts, 94 percent of all HIV-specific incidents in which immigrants had contact with the criminal system were under California’s felony offense against solicitation while HIV-positive.

-Eighty-three percent of the immigrants who had contact with the system based on their HIV-positive status were born in Mexico, Central or South America, or the Caribbean.

-While U.S. born people were divided fairly evenly between men and women, immigrants were overwhelmingly men: 88 percent of foreign born individuals in the group were men. (It should be noted that “men” may include transgender male-to-female individuals. Problems created by a lack of data on transgender people within criminal justice databases are highlighted in the report.)

HIV Criminalization Against Immigrants in California was developed by analyzing the California Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) data on HIV offenses in California, exploring the demographics and experiences of foreign born individuals as compared to their U.S. born counterparts. Future research beyond the enforcement data may explore whether initial patterns seen by sex and place of birth are perpetuated in other criminal systems or under other offenses. Future research can also explore the influence of sexual orientation and gender identity as a potential driver to the criminal system and as a potential mediating factor in experiences once in the system. This will help provide a more nuanced and complete picture of the experiences of people who are criminalized based on their HIV-positive status.

Read the report.

The Williams Institute, a think tank on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, is dedicated to conducting rigorous, independent research with real-world relevance.

HIV criminalisation advocacy must extend beyond HIV specific statutes

September 29, 2016

The fight to combat HIV criminalization is not new. After years of activism, gains are finally being made to repeal statutes that turn a person’s knowledge of their HIV status into a crime.

Just this year, Colorado’s HIV modernization bill comprehensively repealed almost all of the HIV-specific statutes in the state. This is an evidence-based success: Criminalizing people’s HIV status does not inhibit HIV transmission, but instead turns their knowledge and treatment of that status into evidence of a crime. This weaponizes their knowledge and their enrollment in the very care public health officials recommend, forcing people to weigh testing and treatment against fear of arrest.

With the growing success in fighting HIV criminalization, it is now time for advocates to take the conversation beyond the repeal of HIV-specific statutes and to confront the larger context of how criminalization encourages HIV transmission.

The growing data on where and when laws criminalizing a person’s status are implemented show that the people in the crosshairs of these laws are often those already criminalized through their engagement in sex work. The ostensible targets of HIV criminalization laws may be people who are not otherwise criminalized, but the data clearly show who faces most of their impact. The more common way that people who are HIV positive are criminalized for their status is not through general HIV criminalization statutes, but through laws that upgrade a misdemeanor prostitution charge to a felony if a sex worker is HIV positive.

The Williams Institute looked at who is charged and convicted of HIV-specific statutes in California found that “[t]he vast majority (95%) of all HIV-specific criminal incidents impacted people engaged in sex work or individuals suspected of engaging in sex work.” Research out of Nashville, Tennessee, corroborated this picture, with charges disproportionately targeting people arrested for prostitution, who then faced a felony upgrade and (until last year) were required to register as sex offenders for being HIV positive. However, these laws are not the only way criminalization increases sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV transmission, and advocacy must expand its vision to include the fuller context.

At the Sex Workers Project, we work with individuals who trade sex across the spectrum of choice, circumstance and coercion. For sex workers, the relationship between criminalization and health is complex and deeply interwoven.

When we look at the role of HIV transmission in the lives of our clients and community, it is not simply HIV-specific statutes, but the tactics of policing and the instability created through criminalization that increase people’s vulnerability. If the long-term goal is to end the spread of HIV, advocacy should target criminalization more holistically and see HIV modernization, or the on-going state-by-state push to repeal these statutes, as just one of the initial steps needed to explore the nexus between public health and criminalization.

When we expand our scope beyond these specific statutes to look at how policing and criminalization encourage HIV transmission, a more complex and multi-layered picture emerges. For instance, the relationship between evidence of a crime and transmission of HIV does not end with simply knowing one’s status. Law enforcement’s use of condoms as evidence of prostitution has a chilling effect. In research on the impact of policing that uses safer-sex supplies as evidence of a crime, many sex workers reported that they were afraid to carry condoms or take condoms from outreach workers, regardless of whether they were engaging in prostitution at that time. Most impacted by these policing practices were transgender women of color, a population acknowledged to be already at higher risk for HIV transmission. Transgender women are commonly profiled as being engaged in sex work, and therefore, were most at risk for being arrested for the mere possession of condoms. This means that policing practices are actively putting the community with the highest vulnerability to HIV at even higher risk of transmission.

Further, policing procedures that inundate areas “known for prostitution” with law enforcement push sex workers into isolated locations to avoid arrest. This means isolation from peers who can provide harm reduction and safety, and from outreach workers who may offer resources — in addition to making sex workers vulnerable to physical and sexual assault, as physical isolation carries its own risk of HIV transmission.

The fight for HIV modernization bills across the country is already having a demonstrable success. The recent Colorado HIV modernization bill shows what a comprehensive policy can look like. Many other state-based efforts have made sure their work encompasses those most impacted by HIV-specific statutes and fought to include in their advocacy sex workers and organizations serving people who trade sex.

But these policy changes should not be where the momentum ends. HIV criminalization is only one part of the larger on-going dialogue on the nexus between criminalization and public health that deeply impacts the lives of marginalized communities. When more people understand how criminalization affects individual and public health, we can expand the impact of our work to address these larger issues and shift our goals to not just avoiding the criminalization of HIV, but also stemming its spread.

Kate D’Adamo is the national policy advocate at the Sex Workers Project at the Urban Justice Center, focusing on laws, policies and advocacy that target folks who trade sex, including the criminalization of sex work, anti-trafficking policies and HIV-specific laws. Previously, Kate was a community organizer and advocate for people in the sex trade with the Sex Workers Outreach Project-NYC and Sex Workers Action New York. She holds a BA in political Science from California Polytechnic State University and an MA in international affairs from the New School University.

Originally published in The Body on 29/09/2016

Canada's HIV disclosure laws are out of date and bad for public health – Opinion piece by Robin Baranyai

Canada’s laws governing HIV disclosure are dangerously out of date. Anyone who tests positive and doesn’t warn their lover can be charged with aggravated sexual assault, carrying a penalty up to life in prison and lifelong registry as a sex offender. Fearing the potential criminal consequences of knowing, some people at risk won’t get tested.

Anyone, naturally, would hope an intimate partner would reveal if he or she was HIV-positive. But the criminal law is a blunt instrument with which to enforce honesty in a relationship. It sends a dangerous message people can assume their sexual partners are HIV-negative unless they reveal otherwise. And it further marginalizes a group already beset by stigma and discrimination.

People with HIV have many reasons for keeping the diagnosis to themselves. They may reasonably fear rejection, damaging public exposure or violence. But sex without disclosure, under the law, is rape; the omission invalidates consent.

Perhaps that made sense in the epidemic’s early days, when the risk was equated with death. But medical advances have changed the landscape.

Sex with HIV is no longer tantamount to Russian roulette. For this we can thank condoms and antiretroviral therapy (ART), which can bring a person’s viral load to undetectable levels. Either one of these measures reduces the risk of transmission to “negligible.” That’s not my opinion — it’s the scientific consensus of 70 leading HIV physicians and medical researchers across Canada.

In cases where there is virtually no risk of transmitting the virus, it’s hardly logical to prosecute non-disclosure. A 2012 Supreme Court ruling has already clarified disclosure is not required in cases where the risk of transmission is extremely low — specifically, when the viral load is undetectable and condoms are used.

Legislators should heed the scientists.

Their verdict is clear: The data supports decriminalizing non-disclosure if just one of these measures — effective ART or condom use — is in place to protect one’s partner. The consensus paper was published in 2014 to remedy the poor understanding of HIV transmission among prosecutors and judges. The authors expressed an ethical duty not only in the interest of justice, but also “to remove unnecessary barriers to evidence-based HIV prevention strategies.” Two years later, we’re still not listening.

Canada is a world leader in HIV criminalization, according to the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. At least 180 people have been prosecuted for non-disclosure. Half of these were in Ontario, with at least three new charges just this summer.

The double standard is no longer appropriate. ARTs have transformed HIV from a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition. Yet there are no criminal penalties for failing to notify a partner of an array of STDs, some of which can lead to infertility or cancer. Instead, quite logically, we promote self-protection through safer sex.

People withhold information about their sexual histories. One hardly expects a full accounting of partners, past STD treatments or other details one might be inclined to omit in the blush of a budding romance. The point is, people can’t assume their partner has told them everything — nor knows everything there is to tell.

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, one in four people with HIV don’t know they are infected. If knowledge of the virus can turn sex into a criminal act, it creates a significant disincentive to seek testing and treatment. That’s a public health disaster.

Put simply: Treatment reduces transmission. If it’s good public policy to encourage HIV testing, then it’s good public policy to make it safe to know the results.

Published in the Melfort Journal on 23/09/2016

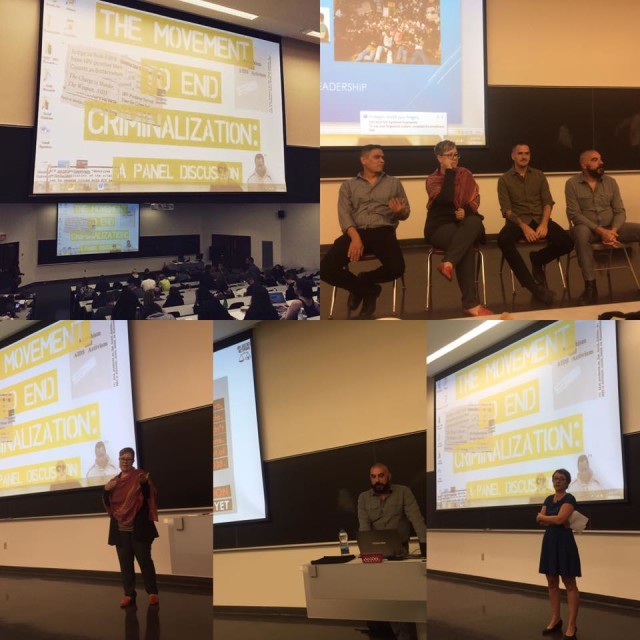

Canada: ‘HIV is not a crime’ documentary premieres in Montreal at Concordia University’s ‘The Movement to End HIV Criminalization’ event

Last week, Concordia Unversity in Montreal, Canada, held the world premiere public screening of HJN’s ‘HIV is not a crime training academy’ documentary, followed by three powerful and richly evocative presentations by activist and PhD candidate, Alex McClelland; HJN’s Research Fellow in HIV, Gender, and Justice, Laurel Sprague; and activist and Hofstra University Professor, Andrew Spieldenner.

The meeting, introduced by Liz Lacharpagne of COCQ-SIDA and by Martin French of Concordia University – who put the lecture series together – was extremely well-attended, and resulted in a well-written and researched article by student jounrnalist, Ocean DeRouchie, alongside a strong editorial from Concordia’s newspaper, The Link.

(The full text of both article and editorial are below.)

Presentations included:

- Edwin Bernard, Global Co-ordinator, HIV Justice Network: ‘The Global Picture: Surveying the State of HIV Criminalisation’

- Alex McClelland, Concordia University: ‘Criminal Charges for HIV Non-disclosure, Transmission and/or Exposure: Impacts on the Lives of People Living with HIV’

- Laurel Sprague, Research Fellow in HIV, Gender, and Justice, HIV Justice Network: ‘Your Sentence is Not My Freedom: Feminism, HIV Criminalization and Systems of Stigma’

- Andrew Spieldenner, Hofstra University: ‘The Cost of Acceptable Losses: Exploring Intersectionality, Meaningful Involvement of People with HIV, and HIV Criminalization’

Articles based on a number of these important presentations will be published on the HJN website in coming

weeks.

The Movement to End HIV Criminalization

Decrying Criminalization

Concordia Lecture Series Prompts Discussion on HIV Non-disclosure

The sentiment surrounding HIV/AIDS is often one of discomfort. But the reluctance to speak openly about such a significant and impactful disease is hurting the people closest to it.

Under current Canadian legislation, HIV non-disclosure is criminalized. It exercises some of the most punitive aspects of our criminal justice system, explained Alexander McClelland, a writer and researcher currently working on a PhD at Concordia.

McClelland was one of four panelists speaking under Concordia’s Community Lecture Series on HIV/AIDS on Thursday, Sept. 15 in the Hall building. The collective puts on multiple panel-based events in order to address the attitudes, laws, and intersections of political and socioeconomic stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS.

Talking About HIV, Legally

There are three distinct charges that guide prosecutors in HIV cases—transmission (giving the disease to someone without having disclosed your status), exposure (e.g. spitting or biting) and non-disclosure (not informing a sexual partner about your HIV/AIDS status).

Aggravated sexual assault and attempted murder are some of the charges that defendants often face, explained Edwin Bernard, Global Coordinator for the HIV Justice Network, during the discussion.

While there are clearly defined situations in which you are legally obligated to tell a sex partner about your HIV status, there are no HIV-specific laws. This results in the application of general law in cases that are anything but general.

In 2012, the Supreme Court of Canada established that “people living with HIV must disclose their status before having sex that poses a ‘realistic possibility of HIV transmission.’”

Aidslaw.ca presents a clear map of situations in which you’d have to tell a sex partner about your status because, in fact, it is not in all scenarios that you’d be legally required to have the discussion.

A lot of it depends on your viral load—the amount of measurable virus in your bloodstream, usually taken in milliliters. A “low” to undetectable viral load is the goal, and is achieved with anti-viral medication.

Treatment serves to render HIV-positive individuals non-infectious, and therefore lowering the risk of transmission. A “high” viral load indicates increased amounts of HIV in the blood.

If protection is used and with a low viral load, one might not have to disclose their status at all.

That said, there is a legal obligation to disclose one’s HIV-positive status before any penetrative sex sans-condom, regardless of viral load. You’d also have to bring it up before having any sex with protection if you have a viral load higher than “low.”

But not all sex is spelled out so clearly.

Oral sex, for instance, is a grey area. Aidslaw.ca says, “oral sex is usually considered very low risk for HIV transmission.” They write that “despite some developments at lower level courts,” they cannot say for sure what does not require disclosure.

There are “no risk” activities. Smooching and touching one another are intimate activities that, as health professionals say, pose such a small risk of transmission that there “should be no legal duty to disclose an HIV-positive status.”

Moving Up, and Out of Hand

Court proceedings are based on how the jury and judge want to apply general laws to specific instances. There are a lot of factors that can influence the outcome.

The case-to-case outlook leads to the criminal justice system dealing with non-disclosure in such a disproportionate way, said McClelland.

The situation begs the question: “Why is society responding in such a punitive way?” asked McClelland.

This isn’t to say that not disclosing one’s HIV status “doesn’t require some potential form of intervention,” he explained, adding that intervention could incorporate counseling, mental-health support, encouragement around building self-esteem and learning how to deal and live with the virus in the world. “But in engaging with the very blunt instrument that is the criminal law is the wrong approach.”

He continued to explain that the reality of the criminalization of HIV ultimately doesn’t do anything to prevent HIV transmission.

“It’s just ruining people’s lives,” said McClelland, who has been interviewing Canadians who have been affected by criminal charges due to HIV-related situations. “It’s a very complex social situation that requires a nuanced approach to support people.”

“It’s just ruining people’s lives. It’s a very complex social situation that requires a nuanced approach to support people.” – Alexander McClelland, Concordia PhD student

Counting the Cases

The Community AIDS Treatment Information Exchange, a Canadian resource for information on HIV/AIDS, states that about 75,500 Canadians were living with the virus by the end of the 2014, according to the yearly national HIV estimates.

That number has gone up since. On Monday, Sept. 19, Saskatoon doctors called for a public health state of emergency due to overwhelmingly increasing cases of new infections and transmission, according to CBC.

In Quebec, there have been cases surrounding transmission and exposure. In 2013, Jacqueline Jacko, an HIV-positive woman, was sentenced to ten months in prison for spitting on a police officer—despite findings that confirm that the disease cannot be transmitted through saliva.

In this situation, Jacko had called for police assistance in removing an unwelcome person from her home. Aggression transpired between her and the officers, resulting in her arrest and eventually her spitting on them, according to Le Devoir.

“[This case] is so clearly based on AIDS-phobia, AIDS stigma and fear,” added McClelland, “and an example of how the police treat these situations and use HIV as a way to criminalize people.”

Police intervention is crucial in the fight against HIV criminalization. McClelland urged people to consider the consequences of involving the justice system in these kinds of situations.

“It’s important to understand that the current scientific reality for HIV is that it’s a chronic, manageable condition. When people take [antivirals] they are rendered non-infectious,” he said. “They should then understand that the fear is grounded in a kind of stigma and historical understanding of HIV that is no longer correct today.”

The first instinct, or notion of calling the police in an instance where one feels they may have been exposed to the virus in some way is “mostly grounded in fear and panic,” he said.

“[Police] respond in a really disproportionate, violent way towards people—so I would consider questioning, or at least thinking twice before calling the police,” McClelland explained.

On the other hand, he suggested approaching the situation in more conventional, educational and progressive methods.

“I think it could be talked through in different ways—by going to a counselor, talking to a close friend, engaging with a community organization, learning about HIV and what it means to have HIV, and understanding that the risk of HIV transmission are very low because of people being on [antivirals].”

As for the current state of Canadian legislation, there are a lot of complexities that hinder heavy-hitting changes to the laws.

Due to the Supreme Court’s rulings in 2012, they are unlikely to review the decision for another decade. For now, the main course of action is “on the ground,” said McClelland. From mitigating people from requesting police involvement in order to “slow down the cases,” to raising awareness through events such as Concordia’s Community Lecture Series, and engaging with the people to resolve issues in community-based ways and collective of care.

Then, McClelland said, “trying to do high-level political advocacy to get leaders to think about how they can change the current situation” would be the next step.

Editorial: Community-Based Research is the Key to HIV Destigmatization and Decriminalization

Receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis is already a life sentence. The state of Canada’s legal system threatens to give those living with the virus another one.

An HIV diagnosis is accompanied by its own set of complexities that are not encompassed in Canada’s criminal law. By pushing HIV non-disclosure cases into the same box as more easily defined assault cases, we are generalizing an issue that frankly cannot be simplified.

This does not reflect the reality that one faces when living with HIV. Criminalizing the virus further stigmatizes what should and could be everyday activities.

This puts the estimated 75,000 Canadians living with HIV at risk of being further isolated. This takes us backwards, considering the scientific progress that has been made to make living with the virus manageable. Under the proper antiviral medication, one’s risk of transmitting the disease is incredibly low. This stigma is rooted in an antiquated understanding of what HIV is and the associated risks—much of that fear having emerged primarily as a result of homophobia.

Further, with over 185 cases having been brought to court, Canada is leading in terms of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure. This pushes marginalized communities farther away. According to estimates from 2014, indigenous populations have a 2.7 higher incidence rate than the non-indigenous Canadian average. Gay men have an incidence rate that is 131 times higher than the rest of the male population in Canada.

As of Sept. 19, doctors in Saskatchewan are calling on the provincial government to declare a public health state of emergency, with a spike in HIV/AIDS cases around the province.

In 2010, it’s reported that indigenous people accounted for 73 per cent of all new cases in the province. Outreach and treatment for these communities are at the forefront of Saskatchewan’s doctor’s recommendations for the government.

With such a highly treatable virus, however, the problem should never have gone this far. It is an excerpt from a much bigger issue.

As we can see from the available statistics, HIV—both the virus and its criminalization—is a mirror for broader inequalities that exist within society. HIV related issues disproportionately affect racialized people, gender non-conforming people, and other marginalized groups.

Discussions around HIV also must include discussions around drug use. The heavy criminalization of injection drugs has created a context where users are driven deep underground, thus putting them at an incredibly high risk for contracting the virus. Treating drug use as a health rather than a criminal issue is an integral part of any effective HIV prevention strategy. Safe injection sites, such as Vancouver’s InSite, have made staggering differences in their communities and prove to be a positive way of combating the spread of HIV.

This is just one of the many ways that we can control the spread of HIV without judicial intervention, without turning the HIV-positive population into criminals.

Using community-based research enables us to not only understand the needs of the affected population—particularly when it comes to understanding the almost inherent intersectionality associated with the spread of HIV—but also allows us to better target our resources towards those who need it most.

Often times, that stretches to include those closest to HIV-positive individuals. Spreading awareness, and developing resources and a support network for them is just as important in fighting the stigmatization of the virus.

The Link stands for the immediate decriminalization of HIV non-disclosure, and the move towards restorative justice systems in non-disclosure cases. As always, those directly affected by an issue are the ones with who are best positioned to create a solution—something that the restorative justice framework embraces.

The disclosure of one’s HIV status is important. Jailing those who don’t disclose it, however, won’t make the virus go away. It simply isolates the problem, places it out of site and out of mind.

Criminalizing HIV patients is less about justice than it is about appeasing the baseless fears of the general population. It’s time for a more effective solution.

Video and written reports for

Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation at AIDS 2016

now available

On 17 July 2016, approximately 150 advocates, activists, researchers, and community leaders met in Durban, South Africa, for Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation – a full-day pre-conference meeting preceding the 21st International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2016) to discuss progress on the global effort to combat the unjust use of the criminal law against people living with HIV. Attendees at the convening hailed from at least 36 countries on six continents (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America).

Beyond Blame was convened by HIV Justice Worldwide, an initiative made up of global, regional, and national civil society organisations – most of them led by people living with HIV – who are working together to build a worldwide movement to end HIV criminalisation.

The meeting was opened by the Honourable Dr Patrick Herminie, Speaker of Parliament of the Seychelles, and closed by Justice Edwin Cameron, both of whom gave powerful, inspiring speeches. In between the two addresses, moderated panels and more intimate, focused breakout sessions catalysed passionate and illuminating conversations amongst dedicated, knowledgeable advocates.

WATCH THE VIDEO OF THE MEETING BELOW

A tremendous energising force at the meeting was the presence, voices, and stories of individuals who have experienced HIV criminalisation first-hand. “[They are the] folks who are at the frontlines and are really the heart of this movement,” said Naina Khanna, Executive Director of PWN-USA, from her position as moderator of the panel of HIV criminalisation survivors; “and who I think our work should be most accountable to, and who we should be led by.”

Three survivors – Kerry Thomas and Lieutenant Colonel Ken Pinkela, from the United States; and Rosemary Namubiru, of Uganda – recounted their harrowing experiences during the morning session.

Thomas joined the gathering via phone, giving his remarks from behind the walls of the Idaho prison where he is serving two consecutive 15-year sentences for having consensual sex, with condoms and an undetectable viral load, with a female partner.

Namubiru, a nurse for more than 30 years, was arrested, jailed, called a monster and a killer in an egregious media circus in her country, following unfounded allegations that she exposed a young patient to HIV as the result of a needlestick injury.

Lt. Col. Pinkela’s decades of service in the United States Army have effectively been erased after his prosecution in a case in which there was “no means likely whatsoever to expose a person to any disease, [and definitely not] HIV.”

At the end of the brief question-and-answer period following the often-times emotional panel, Lilian Mworeko of ICW East Africa, in Uganda, took to the microphone with distress in her voice that echoed what most people in the room were likely feeling.

“We are being so polite. I wish we could carry what we are saying here [into] the plenary session of the main conference.”

With that, a call was put to the floor that would reverberate throughout the day, and carry through the week of advocacy and action in Durban.

This excerpt is from the opening of our newly published report, Challenging HIV Criminalisation at the 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, July 2016, written by the meeting’s lead rapporteur, Olivia G Ford, and published by the HIV Justice Worldwide partners.

The report presents an overview of key highlights and takeaways from the convening grouped by the following recurring themes:

- Key Strategies

- Advocacy Tools

- Partnerships and Collaborations

- Adopting an Intersectional Approach

- Avoiding Pitfalls and Unintended Consequences

Supplemental Materials include transcripts of the opening and closing addresses; summaries of relevant sessions at the main conference, AIDS 2016; complete data from the post-meeting evaluation survey; and the full day’s agenda.

Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation at AIDS 2016 by HIV Justice Network on Scribd

Ethics of consent explored in provocative article highlighting concerns with criminalising HIV non-disclosure

Joyce Short was young and single, enjoying a thriving career on Wall Street, when she went out with some friends to a bar after work. She met a “very handsome, debonair young man” who seemed perfect for her: Jewish, single, with a degree in accounting from NYU. She would learn much later, after they had begun dating, that none of this was true. Now, she has a mission: she wants to show people the seriousness of what she calls “rape by fraud.”

“I am going to shout it from every rooftop,” Short told VICE. “All lies that undermine a person’s self-determination regarding their reproductive organs are a form of assault.”

Most of us have played with the truth or held back information about ourselves to impress someone—white lies, like “Yeah, I thought Interstellar was brilliant too!” or “What a coincidence, I also love winter hiking!” Short is not alone, however, in thinking that such lies can sometimes cross a line. And as the law stands in America, cases like Joyce’s—in which someone deceives their partner to get them into bed—are not illegal.

In 2013, Tom Dougherty, a philosophy professor at Cambridge University, published apaper arguing that if you lie or withhold information about anything that would be considered a deal-breaker by your partner—anything that, had they known it, would have changed their mind about sleeping with you—you have sexually assaulted them. The logic is simple: If your partner had known the truth beforehand, they wouldn’t have consented, and the sex wouldn’t have happened. Therefore, there was no consent. And sex without consent is assault. Fiona Elvines, of the UK national charity Rape Crisis, put this view bluntly to the Telegraph in 2014: “If you need to trick someone into having sex with you, you’re a perpetrator.”

The deal-breaker view is based on the powerful idea that free and open consent is an absolute requirement for all sexual activity. President Obama has, for instance, launched the “It’s On Us” campaign, aimed at teaching people that all non-consensual sex is assault. But for consent to be free and open, it seems that it should also be fully informed. That’s the standard we hold people to in medicine and business—why not sex? As the Anti Violence Project at the University of Victoria explained, “Informed consent means that someone who is being asked for their consent has full information about what they are being asked to consent to.” In other words, we should have all the information that we consider relevant before getting into bed with someone.

Joyce Short wants us to go further than moral condemnation. “Lying to induce sex is not seduction, it’s a crime,” she told VICE. After her experience, Short has become vocal about the need to reclassify lying to one’s sexual partner as a form of criminal sexual assault. Jed Rubenfeld, a professor at Yale, recently argued in the Yale Law Journalthat this view is the logical outcome of the importance we now place on fully-autonomous consent as a precondition to sexual activity.

Some lawmakers agree. Today, American laws generally make two kinds of sexual deception illegal: cases where someone impersonates a person’s partner (by sneaking into their bedroom at night, for instance), and cases where someone such as a doctor tricks a patient into thinking a sex act is actually some sort of medical procedure. Legislators in two states have proposed broadening the law to make it illegal, as Short thinks it should be, to deceive someone to get them into bed: An assemblyman in Massachusetts proposed such a law in 2008, as did a New Jersey legislator in 2014. Both proposals were defeated. However, as the national dialogue around sexual assault continues, there may well be similar attempts in the future.

But others have concerns over the push to criminalize sexual deception. First, if we do make sexual deception criminal, it would give enormous power to police and prosecutors to regulate our sexual lives—for example, to draw the line when it comes to determining exactly what separates a white lie from true deception. “If we are going to invite the criminal justice system to adjudicate relationships, I don’t think the result is going to be a good one,” Kim Buchanan, a criminal justice researcher in Connecticut who has spoken publicly on the issue, told VICE.

Second, if we move to prosecute sexual deception, those targeted will likely be people who are already vulnerable or stigmatized. It is revealing that in the United States, one very specific, additional form of sexual deception is aggressively criminalized and prosecuted: the failure to disclose one’s HIV status to your partner. As the Center for HIV Law and Policy has documented, nearly every state has prosecuted people for HIV non-disclosure. No equivalent laws criminalize the failure to disclose diseases that are much easier to transmit, such as herpes. “There are no public health reasons to single out this particular deception,” said Buchanan, who published a paper last May documenting the history of HIV prosecutions in the US.

There have also been cases of people prosecuted for so-called “gender fraud”—lying about, or failing to disclose, their birth gender to sexual partners. Sean O’Neill wasconvicted of this in Colorado in 1996, and, while his case proved an isolated one in the US, there has been an upsurge of such prosecutions in the UK, with five people convicted since 2012.

Consent must continue to be at the forefront of all discussions about right and wrong when it comes to sex. But as the problem of sexual deception—and the ire of victims like Short—shows, for American courts, many thorny problems remain to be solved when it comes to self-disclosure and sexual ethics.

Neil McArthur is the director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics at University of Manitoba, where his work focuses on sexual ethics and the philosophy of sexuality. Follow him on Twitter.

US: Jacob Anderson-Minshall from HIV Plus mag reacts to the latest biting case in Marlyand

When will law enforcement get the message? HIV is neither a death sentence nor transmittable through saliva. So why do they keep arresting HIV-positive people for spitting and or biting and, as in the latest case, charging them with attempted murder?

According to the Baltimore, Maryland-based Capital Gazette, 46-year-old Jeffery David Crook, has been charged with attempted murder for allegedly biting an Anne Arundall County police officer during a tussle.

Crook is being held on half a million dollar bond and has reportedly been charged with multiple counts related to an alleged burglary and the assault on the officer. Crook was reported to the cops after “banging” on the outside of the home of Crook’s ex-boyfriend. Refused entry into the home, Crook allegedy “forced his way” into the house through a sliding glass door and was punched in the face by another man who was in the house.

Officers reported that they located Crook “rambling and incoherent” in an upstairs bedroom and he refused to obey their commands. When they attempted to forcedly arrest him, he resisted so a scuffle ensued. Police say that Crook was then Tasered, which, they allege, had no effect on him, and Crook bit an officer’s arm.

Police stated that the bite broke the officer’s skin, but it was Crook who was immediately transported to a local hospital center for “minor injuries,” the Gazette reported, citing local court records. “While there, he indicated that he was HIV-positive and bit the officer knowing the risk of transmitting the infection.”

Police spokesman Lt. Ryan Frashure said he couldn’t recall another incident where an officer was exposed to a “highly infectious disease,” especially “where it was done intentionally.”

Crook was charged with attempted second-degree murder, home invasion, second-degree assault, third-degree burglary, and reckless endangerment, according to court records.

From a public and mental health perspective, there are so many things wrong with this story, it’s hard to know where to begin. Crook’s mumbling, incoherent demeaner should have been a sign he may have been suffering from mental health issues. After entering his former partner’s house (through an unlocked sliding glass door, mind you), he was assaulted and his lip was cut. But instead of calling mental health professionals, officers tried to cuff him. When he struggled, they tased him. Although they reported that Tasing “had no effect,” he was taken to a hospital. Since few suspects are taken to a medical center for “minor injuries” before being interogated, it seems likely they realized he could not give clear answers because of his condition.

More to the point, once at the hospital, Crook disclosed his HIV status. His indication that he bit the police officer “knowing the risk of transmitting the infection,” could have been him simply acknowledging he was aware of his HIV status before he bit the man, or even that he knew there was little or no risk of transmitting HIV through saliva.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is clear “HIV isn’t spread through saliva.”

According to the CDC, biting, spitting, and throwing body fluids all carry “negligible” risk of infection. It is particularly disheartening for activists fighting the criminalization of HIV when poz individuals are convicted of felony crimes for having spat at, bit, or thrown fluids at an officer when it is nearly impossible to transmit HIV that way.

In this specific case, no doubt the argument is that Crook was bleeding from the mouth when he bit the officer hard enough to break skin. But breaking skin and having a small amount of each person’s blood comingling is still highly unlikely to transmit HIV.

Even if a person with HIV gets hurt playing tackle football or boxing at the gym, it’s “highly unlikely that HIV transmission could occur in this manner,” according to the University of Rochester Medical Center. “The external contact with blood that might occur in a sports injury is very different from direct entry of blood into the bloodstream, which occurs from sharing needles or works.”

Even if the officer in question did defy all odds and turn up HIV-positive, there’s no way to be sure it was transmitted in this occassion. Moreover, there’s still a significant problem with the charge of attempted murder. Like many laws that criminalize behavior like sex work or add sentencing penalties only for those who are HIV-positive, charging someone with attempted murder instead of assault is based entirely on the outdated equation that HIV equals death. It’s based on an outdated view of the HIV-positive body not as a human being but as a “deadly weapon.”

These offensive tropes are decades out of date, have been out-and-out discredited by modern science, and rendered obsolete by the development of highly active antiretroviral medications that have transformed HIV from a terminal disease to a manageable chronic condition.

And yet, when confronted with even the tiniest of bodily fluid of HIV-positive individuals, police officers continue to overreact with fear (the officer in the Crook case “remained out of work” days after the incident) and arrest people for actions that cannot transmit HIV, simply because they discover their alleged perp also has HIV.

Around the country, district attorneys in these cases continue to charge HIV-positive individuals with crimes for things that are not criminal, continue bumping up simple charges from misdemeanors to felonies just because the individuals involved are poz, and continue to claim that exposure to HIV is a death sentence when it isn’t. Judges continue to accept these arguments, and continue handing down these overblown sentences, often without the abiility for parole.

Most of the law and order representatives who embrace HIV criminalization do so out of ignorance, but some are aware of the facts and proceed anyway because the law was written in such a way that facts, medical findings, and scientific proof simply have no bearing on the case.

Many of those who are serving extended prison terms have not even transmitted HIV to another person (think Michael Johnson in Missouri and Kerry Thomas in Idaho, both serving 30 year sentences). Yet they often face sentences higher for spitting or having sex without disclosure than if they had actually murdered the person they are accused of “infecting.”

How flawed is this system? And what kind of lesson does this teach people about those living with HIV? For one thing, it teaches that knowing one’s status is a legal liability. In Crook’s case — as in most other cases — the determining factor of guilt is often based on whether the individual knew they were HIV-positive at the time. Spit on a police office without knowing you’re poz, it’s a misdemeanor assault. Spit on an officer once you know have HIV? It’s attempted murder. Neither one can actually transmit HIV.

To us, it’s just insane.

HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE releases ‘HIV IS NOT A CRIME’ training academy video documentary

Today, HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE releases a 30-minute video to support advocates on how to effectively strategise on ending HIV criminalisation, filmed at the second-ever ‘HIV IS NOT A CRIME’ meeting, co-organised by Positive Women’s Network – USA and the Sero Project and held earlier this year at the University of Alabama, Huntsville.

This advocacy video distils the content of the three-day training academy into four overarching themes: survivors, victories, intersectionality and community.

Filmed, edited and directed by HIV Justice Network’s video advocacy consultant, Nicholas Feustel, of georgetown media, it features interviews conducted by Mark S King of MyFabulousDisease.com.

“The idea,” says HIV Justice Network’s Global Co-ordinator Edwin J Bernard, who wrote, narrated and produced the video, “is that it can be used as a starting point for discussions at HIV criminalisation strategy meetings around the world, to help advocates move forward with their own state or country plans to achieve HIV justice.”

The video was produced by the HIV Justice Network on behalf of HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE, and supported by a grant from the Robert Carr civil society Networks Fund provided to the HIV Justice Global Consortium.

You can share, embed or download the full-length video at: https://youtu.be/B433fMElc_c The video is also being hosted at http://www.hivisnotacrime.com.