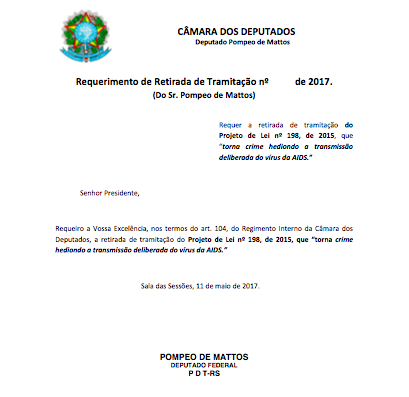

What It’s Like to Be HIV Positive in the Military

Soldiers can be prosecuted for having sex, latest medications aren’t widely available – are the armed forces living in the 1980s when it comes to AIDS?

There’s not much to see in Otisville, New York. The town, with a population of just over 1,000 people, looks like an old mining village with white-painted ranch homes tucked behind the terrain’s rolling hills. The town is on the tip of Orange County, about 60 miles northwest of New York City; turn left down I-209 and you’ll pull into New Jersey, turn right and you’re in Pennsylvania.

For Kenneth Pinkela, Otisville dates back four generations with his family. The old Railroad Hotel and Bar off Main Street – one of the town’s three major roads – is the one his grandfather owned.

“Not a lot to look at, but it’s where I was raised. It’s home,” says Pinkela, driving his Ford pickup through the winding streets.

For Pinkela, Otisville is bittersweet. At 50 years old, the former Army lieutenant colonel, who still holds the shape of a weightlifter, is stuck there. He was forced to move back into his parent’s home three years ago after a military court martial had found him guilty of aggravated assault and battery back in 2012.

But Pinkela never bruised up anyone. Instead, he was tried and charged for exposing a younger lieutenant to HIV, though there was no proof of transmission. Pinkela has been HIV positive since 2007 when he was diagnosed right before deployment to Iraq during the surge.

President Jimmy Carter denounced Pinkela’s trial, and advocates argue it was one of the last Don’t Ask Don’t Tell cases the military tried and won. (Pinkela is also openly gay.) He served eight months in prison, lost his home and was dishonorably discharged from the Army.

Otisville was the only place for Pinkela to retreat to – specifically, back to his mother’s house.

Since being home, things have only gotten worse for Pinkela. His relationship with his mother is strained, he hasn’t had sex for years and doesn’t feel safe in public places.

“The post-traumatic stress I suffer now is worse than what I actually experienced in battle,” he says, pointing out a gunshot wound to his face.

Now, with a felony assault charge, Pinkela is having a hard time finding work even at a hardware store. “I was good at what I did. I loved my job. Now I can’t even get a job.”

Pinkela’s case is not unique. Other HIV positive service members interviewed say that serving their country while fighting for access to HIV care or preventative treatments is an uphill battle rife with bureaucracy, old science and misnomers within the Department of Defense on how HIV is transmitted. Much of the problem has to do with education, but both LGBTQ and HIV advocates say the issue is framed within the military’s staunch conservatism around sexual activity – particularly when it comes to gay sex.

The military isn’t alone in their policies; state laws also give prosecutors authority to charge those who have HIV with felony assault, battery and in some cases rape for having unprotected sex. As a result, gay men are facing what they say is an ethos of discrimination by the military against those who have HIV, including barring people from entering the services and hampering deployment to combat zones.

“It’s not a death disease anymore.”

Nationally, HIV transmission rates have gone down as access to medication and education have increased. But since tracking HIV within the armed forces, positive tests have “trended upwards since 2011,” according to the Defense Health Agency’s Medical Surveillance Monthly Report published in 2015. The highest prevalence of HIV is among Army and Navy men, according to the report.

In 1986, roughly five years after the HIV and AIDS epidemic began, the military began testing for HIV during enlistment, and barred anyone who tested positive. By the time the AIDS crisis began to lessen in the mid-1990s, the Army and Navy started testing more regularly. Now, service members are tested every two years, or before deployment.

Medical advocates say that the current two-year testing policy is partially to blame for the increase by creating a false sense of security against sexually transmitted diseases. The Centers for Disease Control suggest testing for HIV every three months for people who are most at risk of getting the virus, such as gay men or black men who have sex with men.

“The military, depending on how you look at it, could be seen as high risk for contracting HIV,” says Matt Rose, policy and advocacy manager with the National Minority AIDS Council in Washington D.C. “The military likes to treat every service member the same, but it makes testing for HIV inefficient.”

Former Cpt. Josh Seefried, the founder of the LGBTQ military group OutServe, said the group identified HIV as a problem within the armed forces nearly a decade ago after anonymously polling members.

“People have this mindset that since you’re tested and you’re in the military, it must be OK to have unprotected sex,” he says. “That obviously leads to more infection rates.”

Such was the case for Brian Ledford, a former Marine who tested positive right before his deployment out of San Diego. He told Rolling Stone he never got tested consistently because of the routine tests offered by the Navy. “I was dumb and should’ve known better, but I just thought, you know, I’m already getting tested so it’ll be fine.”

But a larger problem for the military is the number of civilians who try to enlist and test positive. The Defense Health Agency last year said there was a 26 percent increase of HIV positive civilians trying to sign up for the service.

All of those people, per military policy, were denied enlistment.

A Department of Defense spokesperson told Rolling Stone that the military denies HIV positive enlistees because the need to complete training and serve in the forces “without aggravation of existing medical conditions.”

But gay military groups say the policy is simply thinly-veiled discrimination.

“This policy, just like every other policy that was put in place preventing LGBTQ people from serving, is discriminatory and segments out a finite group of people,” says Matt Thorn, the current executive director of OutServe-SLDN. “Gen. Mattis during his confirmation said he wanted the best of the best to serve. If someone wants to serve their country they should be allowed to serve their country.”

The U.S. is one of the few Western nations left that have a ban on HIV positive enlistees. In Israel, where service is compulsory, their ban was lifted in 2015. In a press conference, Col. Moshe Pinkert of the Israeli Defense Forces said that “medical advancement in the past few years has made it possible for [those tested positive] to serve in the army without risking themselves or their surroundings.”

And as more countries begin to change their attitudes toward HIV and embrace a more inclusive military policy, there is hope that the U.S. might follow suit.

“Lifting the ban on transgender service members and Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was because a lot of other countries had lifted those bans, as well,” says Thorn. “In general, we don’t have a lot of good education awareness within the military on being HIV positive. People are looking back and they’re reflecting back on those initial horrors. But the truth of the matter is that it’s not a death disease anymore.”

Stuck in the 1980s

In July 2007, Pinkela was just about to be deployed out of Fort Hood when he was brought into an office; he was then told the news about his HIV status.

After the shock set in, he returned back to the D.C. area where he was required to sign what is known in the military as a “Safe Sex Order.” The order requires service members to follow strict guidelines on how they approach contact with others due to their diagnosis. If violated, soldiers can face prosecution or discharge.

“That piece of paper was a threat,” says Pinkela. “I couldn’t believe it was something that we did. Even to this day I look back on it and can’t believe that someone thought the order was okay.”

The Safe Sex Orders differ slightly between the military branches, but some of the details are troubling to medical professionals who say it appears as though the military is stuck in the 1980s.

For example, guidelines in the Air Force and Army tell soldiers to keep from sharing toothbrushes or razors. But the science and medical communities have known for decades that HIV can’t survive outside of the human body and needs a direct route to the bloodstream – something razors and toothbrushes can’t provide.

The Navy and Marine guidelines also tell service members to prevent pregnancy, as transmission of HIV between the mother and child may occur. But transmission between mother and child has become exceedingly rare.

“It’s your right to procreate,” says Catherine Hanssens, executive director of the HIV Law and Policy Center. “To effectively say to someone that because you’re HIV positive, even if you inform your partner, you shouldn’t conceive a child raises constitutional issues.”

Since 2012, HIV transmission has had a dramatic turnaround – partially due to preventative treatments that make the virus so hard to contract.

When someone is on HIV medication, they can reach an “undetectable” level of virus in their blood. At that point, transmission of HIV without a condom is nearly impossible, according to studies conducted in 2014 and released last year.

Rolling Stone reached out to the Department of Defense to specify why, given the medical advancement and low transmission rate, Safe Sex Orders were still being issued in their current format. The department defended the orders, saying “It is true that the risk is negligible if… the HIV-infected partner has an undetectable HIV viral load. However, it cannot be said that the risk is truly zero percent.”

If a service member breaks any of these rules, the military can charge them under the Uniform Code of Military Justice with assault, battery, rape or conduct unbecoming of an officer or gentleman.

Though department officials told Rolling Stone that “the Army does not use the [policy] to support adverse action punishable under UCMJ,” Hanssens’ organization currently represents service members who are facing charges as a result of not following their Safe Sex Order.

But military advocates – and even their staunch opponents – have said the U.S. military is just falling in line with other states throughout the country that criminalize HIV transmission and exposure. There are currently 32 states that have laws on the books related to HIV.

“Safe Sex Orders are unfortunately consistent with some laws enacted within certain states,” says Jonathon Rendina, an Assistant Professor at Hunter College at The City University of New York’s Center for HIV and Education Studies and Training. “What the military is doing is no different that what many civilian lawmakers are doing.”

In 2011, California Rep. Barbara Lee introduced a bill that would end HIV criminalization nationwide, though it failed to pass. In 2013, she helped push a line in the National Defense Authorization Act that forced the Department of Defense to review its HIV policies; though, only the Navy made changes to their Safe Sex Order.

“Too often, our brave service members are dismissed – or even prosecuted – because of their status,” Lee tells Rolling Stone in an email. “These shameful policies are based in fear and discrimination, not science or public health.”

Such was the case for Pinkela, who feels that the military has been using HIV as a reason to prosecute and kick out gay men since the legislative repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell in 2010.

“I could not have sex. And even if I had sex and I told somebody, someone in the military could still prosecute me. They have this little piece of paper that lets some bigot and someone who doesn’t understand us, slam us and put us in jail,” he says.

And he’s not alone. Seefried, the retired Air Force captain, says he advises his gay friends – he calls them “brothers” – not to join the military.

“Right after Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was repealed, I came out and I said that gays should join to help change the culture,” Seefried says. “Now, I tell them not to not sign up… I just think that policies are very, very bad and unsafe for gays in the military right now.”

Quality care, for some

Travis Hernandez, a former sergeant in the Army, has been on the drug Truvada for just under two years now. He started using the the once-a-day blue pill while stationed at Ft. Bragg after he learned from a hook up that the drug could prevent HIV transmission by nearly 100 percent.

“A guy I was in the Army with and having sex with told me about it, and I was sexually active so it made sense for me to try it,” Hernandez says, adding how his experience getting the drug through the Army was very positive. “The doctors were really open talking about safe sex and everyone was very nice. I didn’t have any issues getting the drug.”

Hernandez finished his Army service last year and continues to receive Truvada through his veteran health benefits. But his story is not similar to everyone else’s.

The military provides access to Truvada through it’s healthcare provider TriCare, but only for certain individuals. Each military branch makes their own rules for who can get access.

Emails obtained by Rolling Stone between the National Minority AIDS Council and military health officials confirm that there are different protocols for prescribing Truvada between the service branches and its members without any specific reason.

“The military likes to set their own rules, even if it doesn’t always make sense,” says Rose, with the council. “The Army thinks they know what’s best for the Army, and Marines think they know what’s best for the Marines. But they all have different medical requirements that shouldn’t have any dissimilarities.”

In a statement, Military Health officials within the Department of Defense say they are conducting studies on the effectiveness of Truvada in certain situations, such as while on flight status or sea duty, and are also looking into barriers service members faced with access to care across the military branches. Among those barriers, Military Health noted that not every military hospital has infectious disease specialists who would prescribe the drug.

Truvada does not require a prescription from an infectious disease doctor, though. And the different policies, Seefried says, shows the lack of scientific competence within the Department of Defense and the policies they create.

“Navy Pilots, for example, can take Truvada while on the flight line, but Air Force pilots cannot while they are on the flight line,” says Seefried. “These military branches have different chains of command, so they have different policies that all agree on nothing. It’s just disjointed, and not grounded in science.”

Once a prison, now a home

The charges brought against Pinkela are confusing – even to lawyers who have reviewed his case. Hanssens, with the HIV Law and Policy Center, was one of them.

“What happened to him makes no sense,” she said.

Typically, when a prosecutor files charges, certain requirements have to be met. For assault and battery, according to the UCMJ, one of the primary actions has to be an unwanted physical and violent encounter or an action that is likely to cause death. There are no statutes that label the virus as a determinant for the charge.

Despite there not being an authorization on the books, scores of HIV positive service members like Pinkela have been brought before a court martial with felony assault and battery charges.

Pinkela’s case had gone through six prosecutors who thought the case was too weak before one finally picked it up, according to Pinkela.

And Pinkela’s court martial testimonies are even more bizarre: the soldier never said Pinkela and he had sex, nor did he ever say that Pinkela was the one who transmitted the virus to him. Instead, the evidence came down to an anal douche that may have been used and could’ve exposed the young soldier to HIV.

Not possible, says Rendina, the investigator from the City University of New York.

“Like most viruses, HIV is destroyed almost immediately upon contact with the open air,” he said. “The routes of transmission [listed in Pinkela’s case] have an extremely low probability of spreading infection due to the multiple defenses along the route from one body to the next – this is made even more true if the HIV-positive individual is also undetectable.”

When asked about the case, the Army only confirmed Pinkela’s charges but wouldn’t comment on the nature of the case or how HIV is prosecuted, generally, within the armed forces.

Pinkela has run out of appeals and is forced to now move forward with what little means he has. But in true spirit of service, he has found a new way to give back to the small town that he’s been forced to live in. In May, Pinkela plans to announce his plans to run for office in Otisville.

“I still believe in this country. And I still believe in the service, no matter that it’s the same system that allowed for this to happen to me,” he said.

In an effort to move past the experience, Pinkela and a friend went to last year’s Burning Man – the art and music festival held in Death Valley, California. There, when the fires began burning on the last day, he wrapped up his Army uniform, tied it off and threw it in a fire. He said it was one of the most cathartic moments he’s felt since being back in the Army.

Published in Rolling Stones on May 20, 2017