Following a Constitutional challenge initiated in February 2016 by the Multisectoral Group on HIV / AIDS and STIs of Veracruz and the National Commission on Human Rights, and supported by HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE, Mexico’s Supreme Court of Justice yesterday found by eight votes (out of 11) that the amendment to Article 158 of the Penal Code of the State of Veracruz to be invalid as it violates a number of fundamental rights: equality before the law; personal freedom; and non-discrimination.

The full ruling is not yet available, but according to a news story published yesterday in 24 Horas.

…it was pointed out that the criminal offense is “highly inaccurate” because it does not establish what or what is a serious illness, besides it is not possible to verify the fraud in the transmission [and] that although the measure pursued the legitimate aim of protecting the right to health, especially for women and girls, the measure did not exceed the analysis of need because it was not ideal and optimal for the protection of that purpose, especially as [Veracruz] already criminalised the ‘willful putting at risk of contagion of serious illnesses’…

Additionally, Letra S reports,

The Minister President of the Court, Luis María Aguilar Morales, took up the recommendations of the Joint United Nations Program on HIV / AIDS and the Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation, regarding the criminalization of HIV, and argued that this article left to the will of the investigating authority to decide which diseases will be considered as serious and which will not, going against the principle of legality, which implies that the crimes cannot be indeterminate or ambiguous.

In this case, the President said, the article did not establish whether STIs are only those considered serious or any, regardless of their severity. In turn, the justices determined that the resolution has a retroactive effect, that is, that those persons tried under the offense established by this article, the resolutions are invalidated.

Background

On August 4, 2015, the Congress of the State of Veracruz approved an amendment to Article 158 of the Criminal Code in order to add the term Sexually Transmitted Infections, which included HIV and HPV.

It provided for a penalty ranging from 6 months to 5 years in prison and a fine of up to 50 days of salary for anyone who “willfully” infects another person with a disease via sexual transmission.

The amendment, proposed by the deputy Mónica Robles Barajas of the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico, said the legislation was aimed at protecting women who can be infected by their husbands. “It’s hard for a woman to tell her husband to use a condom,” she said in an interview with the Spanish-language online news site Animal Político.

On February 16, 2016, the National Human Rights Commission responded to the request of the Multisectoral Group on HIV / AIDS and STIs of the state of Veracruz and other civil society organizations, and filed an action of unconstitutionality against the reform in the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, which it said does not fulfill its objective of preventing the transmission of sexual infections to women and girls, but rather creates discrimination of people living with HIV and other STIs.

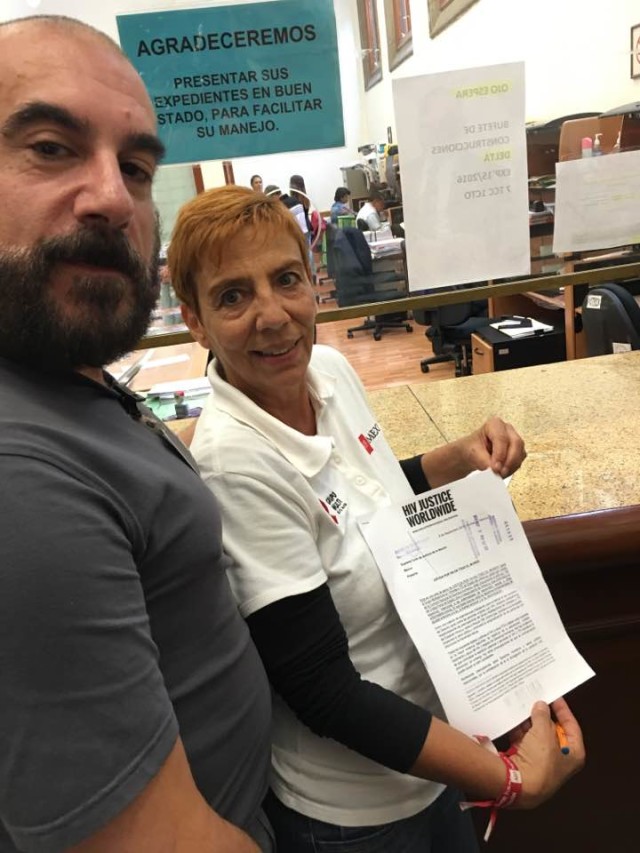

In October 2016, following a press conference at the National Commission on Human Rights (pictured above) that generated a great deal of media coverage, including a TV report, HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE delivered a letter to the Mexican Supreme Court highlighting that a law such as that of Veracruz does not protect women against HIV but rather increases their risk and places women living with HIV, especially those in positions vulnerable and abusive relationships, at disproportionate risk of both proseuction and violence.

In October 2017, the first Spanish-language ‘HIV Is Not A Crime’ meeting took place in Mexico City, supported by the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE coalition where a new Mexican Network against HIV Criminalisation was established.

The Network issued a Statement yesterday which concluded:

We applaud the declaration of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, which gives us the reason for the unconstitutionality request, shared with the National Commission of Human Rights; For this reason, we suggest to the deputies of the Congresses of the State that before legislating, they should be trained in the subject and that they do not forget that their obligation is to defend Human Rights, not to violate them.

Finally, the Mexican Network against the Criminalization of HIV recognizes that there are still many ways to go and many battles to fight, but we can not stop celebrating this important achievement.

Read the English text of the HIV JUSTICE WORLWIDE amicus letter below.

HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE

This is a letter of support from HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE[1] to Grupo Multi VIH de Veracruz / National Commission of Human Rightswho are challenging Article 158 of Penal Code of the Free and Independent State of Veracruz that criminalises ‘intentional’ exposure to sexually transmitted infections or other serious diseases, on the grounds that this law violates a number of fundamental rights: equality before the law; personal freedom; and non-discrimination.

As a coalition of organisations working to end the overly broad use of criminal laws against people living with HIV, we respectfully share Grupo Multi VIH de Veracruz’s concerns around Article 158 which potentially stigmatises people with sexually transmitted diseases and criminalises ‘intentional’ exposure to sexually transmitted infections (potentially including HIV) or other serious diseases.

All legal and policy responses to HIV (and other STIs) should be based on the best available evidence, the objectives of HIV prevention, care, treatment and support, and respect for human rights. There is no evidence that criminalising HIV ‘exposure’ has HIV prevention benefits. However, there are serious concerns that the trend towards criminalisation is causing considerable harm.

Numerous human rights and public health concerns associated with the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure and/or potential or perceived exposure and/or transmission have led the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/ AIDS (UNAIDS) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), [2] the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health,[3] the Global Commission on HIV and the Law[4] and the the World Health Organization[5], to urge governments to limit the use of the criminal law to extremely rare cases of intentional transmission of HIV (i.e., where a person knows his or her HIV-positive status, acts with the intention to transmit HIV, and does in fact transmit it). They have also recommended that prosecutions [for intentional transmission] “be pursued with care and require a high standard of evidence and proof.” [6]

In 2013, UNAIDS produced a comprehensive Guidance Note to assist lawmakers understand critical legal, scientific and medical issues relating to the use of the law in this way.[7] In particular, UNAIDS guidance stipulates that:

- “[I]ntent to transmit HIV cannot be presumed or solely derived from knowledge of positive HIV status and/or non-disclosure of that status.

- Intent to transmit HIV cannot be presumed or solely derived from engaging in unprotected sex, having a baby without taking steps to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, or by sharing drug injection equipment.

- Proof of intent to transmit HIV in the context of HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission should at least involve (i) knowledge of positive HIV status, (ii) deliberate action that poses a significant risk of transmission, and (iii) proof that the action is done for the purpose of infecting someone else.

- Active deception regarding positive HIV-status can be considered an element in establishing intent to transmit HIV, but it should not be dispositive on the issue. The context and circumstances in which the alleged deception occurred—including the mental state of the person living with HIV and the reasons for the alleged deception— should be taken into consideration when determining whether intent to transmit HIV has been proven to the required criminal law standard.”

Moreover, where criminal liability is extended to cases that do not involve actual transmission of HIV (contrary to the position urged by UNAIDS and other experts), such liability should, at the very bare minimum, be limited to acts involving a “significant risk” of HIV transmission. In particular, UNAIDS guidance contains explicit recommendations against prosecutions in cases where a condom was used, where other forms of safer sex were practiced (including oral sex and non-penetrative sex), or where the person living with HIV was on effective HIV treatment or had a low viral load. Being under treatment or using other forms of protections not only show an absence of malicious intent but also dramatically reduces the risks of transmission to a level close to zero. Indeed, a person under effective antiretroviral therapy poses – at most – a negligible risk of transmission[8] and is therefore no different from someone who is HIV-negative.

Moreover, there is growing body of evidence[9] that such laws that actually or effective criminalise HIV non-disclosure, potential or perceived exposure, or transmission, negatively impact the human rights of people living with HIV due to:

- selective and/or arbitrary investigations/prosecutions that has a disproportionate impact on racial and sexual minorities, and on women.

- confusion and fear over obligations under the law;

- the use of threats of allegations triggering prosecution as a means of abuse or retaliation against a current or former partner;

- improper and insensitive police investigations that can result in inappropriate disclosure, leading to high levels of distress and in some instances, to loss of employment and housing, social ostracism, deportation (and hence also possibly loss of access to adequate medical care in some instances) for migrants living with HIV in some cases;

- limited access to justice, including as a result of inadequately informed and competent legal representation;

- sentencing and penalties that are often vastly disproportionate to any potential or realised harm, including lengthy terms of imprisonment, lifetime or years-long designation as a sex offender (with all the negative consequences for employment, housing, social stigma, etc.);

- stigmatising media reporting, including names, addresses and photographs of people with HIV, including those not yet found guilty of any crime but merely subject to allegations.

In addition, there is no evidence that criminalising HIV (or other sexually transmitted infections) help protect women and girls from infections.

Women are often the first in a relationship to know their HIV status due to routine HIV testing during pregnancy, and are less likely to be able to safely disclose their HIV-positive status to their partner as a result of inequality in power relations, economic dependency, and high levels of gender-based violence within relationships.[10]

Such a law does nothing to protect women from the coercion or violence that effectively increases the risk of HIV transmission. On the contrary, such laws place women living with HIV, especially those in vulnerable positions and abusive relationships, at increased risks of both prosecution and violence.

Some evidence suggests that fear of prosecution may deter people, especially those from communities highly vulnerable to acquiring HIV, from getting tested and knowing their status, because many laws only apply for those who are aware of their positive HIV status. [11] HIV criminalisation can also deter access to care and treatment, undermining counselling and the relationship between people living with HIV and healthcare professionals because medical records can be used as evidence in court. [12]

Finally, there is evidence[13] of an additional negative public health impact of such laws in terms of:

- increasing HIV-related stigma, which has an adverse effect on a person’s willingness to learn about, or discuss, HIV; and

- undermining the importance of personal knowledge and responsibility (correlative to degree of sexual autonomy) as a key component of an HIV prevention package, when instead prevention of HIV within a consensual sexual relationship is – and should be perceived as – a shared responsibility.

We hope that the Mexico Supreme Court of Justice takes our concerns and all of this evidence into account when considering the Constitutional Challenge.

Yours faithfully,

Edwin J Bernard, Global Co-ordinator, HIV Justice Network

on behalf of all HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE partners: AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA); Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network; Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+); HIV Justice Network; International Community of Women Living with HIV (ICW); Positive Women’s Network – USA (PWN-USA); and Sero Project (SERO).

[1] HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE is an initiative made up of global, regional, and national civil society organisations working together to end overly broad HIV criminalisation. The founding partners are: AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA); Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network; Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+); HIV Justice Network; International Community of Women Living with HIV (ICW); Positive Women’s Network – USA (PWN-USA); and Sero Project (SERO). The initiative is also supported by Amnesty International, the International HIV/AIDS Alliance, UNAIDS and UNDP.

[2] UNAIDS. Policy Brief: Criminalisation of HIV Transmission, August 2008; UNAIDS. Ending overly-broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission: Critical scientific, medical and legal considerations, May 2013.

[3] Anand Grover. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, June 2010.

[4] Global Commission on HIV and the Law. HIV and the Law: Risks, Rights & Health, July 2012.

[5] WHO. Sexual health, human rights and the law. June 2015.

[6] Global Commission on HIV and the Law. HIV and the Law: Risks, Rights & Health, July 2012.

[7] UNAIDS. Ending overly-broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission: Critical scientific, medical and legal considerations, May 2013.

[8] A.J. Rodger et al., “Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy,” JAMA 316, 2 (12 July 2016): pp. 171–181.

[9]op cit. Global Commission on HIV and the Law.

[10] Athena Network. 10 Reasons Why Criminalization of HIV Exposure or Transmission Harms Women. 2009.

[11] O’Byrne P et al. HIV criminal prosecutions and public health: an examination of the empirical research. Med Humanities 2013;39:85-90 doi:10.1136/medhum-2013-010366

[12]Ibid.

[13]Op cit. Global Commission on HIV and the Law.