By

Robert Suttle

TheBody recently published, “We Keep Ignoring HIV Criminalization,” an article that addressed the lack of attention given to HIV criminalization laws.

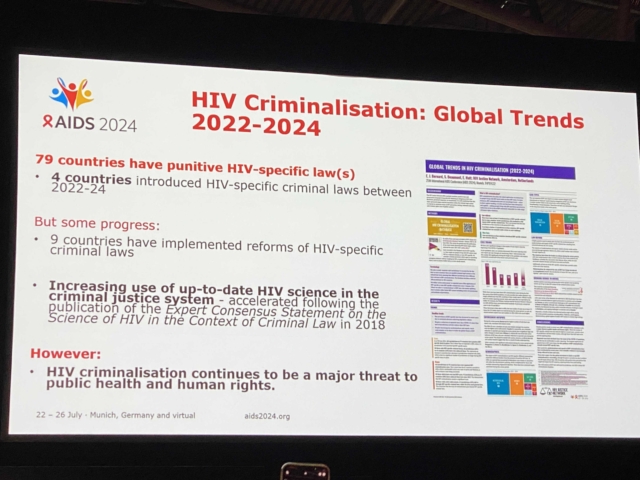

These laws criminalize people living with HIV for a range of actions―such as having sex without first disclosing their serostatus―often, even when they are virally suppressed and therefore incapable of transmitting the virus. As is always the case, ignorance of the law is no defense against it.

In some states, HIV criminalization laws punish people living with HIV for biting or spitting even though, once again, these acts cannot transmit the virus. But losing one’s freedom under these laws doesn’t stop at simple prosecution. In some states, people prosecuted under these laws are required to register on state sex-offender registries, even when no sexual assault has taken place.

It should be noted that prosecuting and equating people living with HIV with rapists and other violent sexual assailants does nothing to decrease HIV transmissions. Rather, as “We Keep Ignoring HIV Criminalization” notes, these harsh measures promulgate stigma, possibly discourage people from getting tested, and place targets on the foreheads of anyone living with the virus.

Beyond this, part of what makes HIV criminalization laws so insidious is that they have additional components to them that can destroy a person’s life in ways that few people are aware of—until they’ve been prosecuted and deemed a “sexually dangerous person” by the state. This is called civil commitment and can keep a person imprisoned indefinitely without the basis of a new offense.

To help shed light on this shadowy form of incarceration and what can happen to people who have been prosecuted for HIV criminalization, TheBody spoke with two members of the Center for HIV Law and Policy: staff attorney Kae Greenberg (pronouns he/him), and policy and advocacy manager Amir Sadeghi (pronouns he/him).

Robert Suttle: The Prison Policy Initiative recently published, “What Is Civil Commitment?” Can you speak about how it can be applied to HIV criminalization, especially when sex offense has been included in the prosecution?

Amir Sadeghi: I’m so glad we’re talking about this. People across the country have been wrestling with this because 20 states have these laws in place. Civil commitment is a system of civil laws that detain people convicted of certain sex offenses long after serving their criminal sentences. This kind of state custody and detention happens on top of somebody’s criminal sentence.

Suttle: So basically an added punishment after one has “repaid their debt to society.” Some people might look at this and celebrate. How do you talk about this with people who are opposed to eliminating these laws?

Sadeghi: I think about questions that people usually ask prison abolitionists: What are you going to do about sexual violence? What are you going to do about these really hard cases?

I think the most important thing I want to foreground in discussions about sex offense civil commitment is that I don’t downplay the harm of sexual violence. It’s a deeply personal and real thing that happens in our society.

However, it is unclear that detaining people with very little due process has any measurable or meaningful impact on reducing gender-based violence and sexual violence. And actually, there’s been a huge mobilization of survivor-led movements and organizations who have begun to condemn harsh responses that happen in their name. For instance: sex-offense civil commitment, sex-offense registries, detention, and state violence.

I think that the history of laws that punish people long after their criminal sentence via sex-offense civil commitment [comes from] highly publicized cases about sexual violence [and has] motivated politicians and the public to react very strongly against these cases. It has created a very draconian system of facilities that many advocates and people who’ve been in sex-offense civil commitment themselves call shadow prisons.

Kae Greenberg: I want to clarify something about people serving or being punished long after their crimes. People are incarcerated because they have been convicted or have pleaded guilty to a crime. But they are in civil commitment because they have been deemed a potential [risk] of reoffending in some way or incapable of controlling themselves. It’s essentially some dystopian RoboCop or Judge Dredd situation where they’re trying to predict whether or not you will potentially commit a future serious crime and, therefore, lock you away from society just in case.

When we talk about the minimal protections in the criminal justice system, like the standard of proof or reasonable doubt, we know that’s a very high standard, hypothetically. Something that would stop you or cause you to make an important life decision. Civil commitment is a much lower standard of proof; it’s just beyond 50%. We only know a little about what happens in these hearings because they are not open to the public.

What’s used is the speculation of mental health practitioners, and I’m not trying to disparage the mental health community. I’m a big proponent of mental health practitioners, but we’re talking about having someone confined indefinitely for something they “might do.” There is potentially no end to this. It’s until [the state] decides that you’re done.

Suttle: Let’s address the elephant in the room: Nushawn Williams. Where do things stand with his ongoing detainment related to the civil commitment in New York?

Sadeghi: Many people know that the Center for HIV Law and Policy (CHLP) has filed amicus briefs supporting Nushawn Williams in the past. We are a proud member of the Free Nushawn Coalition, which was founded by Brian C. Jones and Davina Connor, who I think a lot of HIV activists know warmly and lovingly.

The New York State Department of Health cooperated with prosecutors in the case to criminalize Nushawn Williams. Why did they do this? Because his HIV status and race were weaponized against him. Newspapers called Nushawn an AIDS monster, an AIDS predator. Then-Mayor [of New York City] Rudy Giuliani said he wanted Nushawn Williams tried for, quote, “attempted murder or worse.” There was a horrific stigmatizing frenzy to lock him up and throw away the key.

Nushawn pled guilty in 1999 to statutory rape and reckless endangerment and served his maximum criminal sentence relating to that plea agreement. But in 2010, his release from Wende Correctional Facility in upstate New York was blocked by then–Attorney General Andrew Cuomo, who filed an Article 10 Mental Hygiene Law petition to have Nushawn civilly committed. I think the frenzy and racist spectacle that was made to paint Nushawn as a monster makes it clear that his HIV status and race are major factors in what the state decided to do.

Editor’s note: An example of this spectacle is that two corrections officers reported that Williams “stated that he intended to continue that behavior [sex without sharing his HIV status] upon his release, specifically referencing underage girls”―an absurd and unlikely contention when one considers that such a statement would expose him to undue scrutiny as well as the very punitive treatment he is currently experiencing. In its explanation for why Williams is still detained, the state lists his prior substance use, sexual offenses, prison record prior to 2006, and his “failure to complete sex offender treatment,” without detailing what completion entails. Taken as a whole, it is clear that the state unfairly views Williams as the person he was when he entered prison 24 years ago.

I would just like to let folks know that Nushawn is still in state custody today, well over a decade beyond his maximum criminal sentence. And there is no end in sight to his civil commitment. Many people, especially people living with HIV, were rightfully dismayed and disturbed by the prosecution and the decision to civilly commit him. That has brought, I think, a lot of energy and activism to addressing the systemic issue of sex-offense civil commitment. For instance, Black men in New York are nearly two times more likely to be civilly committed than white men.

Suttle: When you talk about detainment, this is in a civil commitment facility. How do they look? Are they different from prisons?

Sadeghi: They have iron-clanging doors. They are surrounded by barbed wire. You are heavily surveilled and subjected to constant searches. They look like prisons because they are prisons. And people are not being successfully or meaningfully treated. People are being detained and punished, often as political prisoners.

So, you don’t have a lot of the protections afforded by the safeguards of the criminal legal system because you are not in criminal custody anymore. You are a “patient” being “treated” in a “secured treatment facility.”

Suttle: The idea that this is being done against a person’s will is obviously troubling. But how do you respond to people who diminish treatment for a sexual offense as being “not so bad?”

Greenberg: The idea of sex-offender “treatment” is very complicated. If one meaningfully engages in some treatment and talks about anything that could potentially (A) allude to their being a risk to others or (B) shows they engaged in some other potentially criminal activity, they could find themself facing new charges or extended civil commitment―just because they were trying to engage in this treatment honestly.

Being engaged in this kind of sex-offender rehabilitation and treatment is kind of a sword of Damocles. One needs to engage in it enough socially. But, potentially, if one engages with full force, they might be putting themself at further risk of consequence. I join with Amir in saying I’m not trying to minimize sexual violence or what the victims of sexual violence have gone through. But it also scares me to live in a society where we lock up people for something they haven’t done.

If we want to talk about how this is tied to other systems―they’re trying to roll out all kinds of sentencing algorithms to determine what someone’s bail should be. What’s scary is it’s all about whether there’s a scientific way to decide who will recidivate and essentially plan to punish people for future crimes [they might not commit]. Ruha Benjamin has done a lot of writing about this, showing how racist and awful these algorithms and sentencing are. Civil commitment is tied to other larger systems throughout the criminal legal system.

Suttle: Would you say that’s why marginalized groups or people should be concerned about this?

Sadeghi: Yes. It’s a really important issue at the intersection of criminalizing sex identity, class, race, and beyond. Research by the Williams Institute on sex-offense civil commitment has shown that Black men are two times more likely than their white peers to be civilly committed after they’ve already served their criminal sentences.

If you think about sexual violence and you find yourself overwhelmed with a sense that people are irredeemable and need to be warehoused in a cage indefinitely, I’d like you to reflect on how that same mentality and rhetoric has often been used to justify HIV criminalization. HIV criminalization laws are often defended and justified by arguments that they prevent intimate partner violence and sexual violence.

But, in reality, we know that women living with HIV have higher rates of experiencing sexual violence. And that women living with HIV are overwhelmingly overrepresented in arrests and prosecutions of people targeted because of their health status as people living with HIV. So I think when we recognize the truth about HIV, health, and criminalization, we can start to understand the rationale that has gone into justifying detaining people. And then we can think about how the state has used these instruments to target and punish “undesirable people,” who are often also suffering in the middle of an axis of different kinds of marginalization.

Again, I think it’s important to note that networks of survivors of sexual violence think it’s ridiculous to confront unconsensual acts of violence with unconsensual treatment and state violence. And we have to take that seriously.

Suttle: Going back to Nushawn, is there anything that people can do to support him or get involved in the coalition to end civil commitment in New York?

Sadeghi: There is a burgeoning campaign of sexual survivor–led movements, people living with HIV, and racial justice advocates. If you’re feeling animated and ready to challenge these draconian systems that target and criminalize and incarcerate people, please reach out to us at CHLP. We’d love to work with you to challenge and end sex-offense civil commitment and other harsh policies that target, criminalize, and incarcerate folks who have been historically marginalized.

Suttle: What is your hope for the future of health and human rights for communities most affected by these issues?

Greenberg: To a certain extent, my hope combines two parts of the question. Health is seen as a human role and not limited by access. As awful as things are―following the Dobbs decision―we’ve also been presented with an opportunity to reframe some of these issues. So instead of dealing with individual access, individual rights to privacy, individual concerns, we can reframe them as public health concerns and about a right to health. We’ve been stripped down to the bare bones, but I’m holding on to that right now. In terms of hope, we can build up in a way that will reach and impact people who haven’t previously had access to meaningful health care and health.

Sadeghi: Over the years, I’ve observed that in the face of this kind of injustice and stigma, it is so important to build power from the bottom up and by cross-movement organizing. I think we, as HIV advocates and people working in the HIV anti-criminalization space, really need to deepen our relationships, partnerships, and accountability to sex worker–led groups, advocacy groups, sex work decriminalization groups, racial justice groups, and prison industrial complex (PIC) abolitionists.

To do that, we need to partner with and build power with these very communities and people who are most likely to be criminalized because of their health status. I’m excited about that new direction. I think I feel it in our movement that we are going there. And I’m looking forward to seeing what happens over the next few years.

Robert Suttle: Robert Suttle is a New York City-based advocacy consultant and movement leader in the global HIV community with expertise in decriminalization, human rights, and the intersection between equity and social justice.