This week, Toronto’s weekly newspaper, ‘Now’, features four articles on HIV criminalisation and its impact in Canada.

The lead article, ‘HIV is not a crime’ is written from the point of view of an HIV-negative person who discovers a sexual partner had not disclosed to him. It concludes:

After my experience with non-disclosure, I felt some resentment. But while researching this article, I reached out to the person who didn’t disclose to me. We talked about the assumptions we’d both made about each other. It felt good to talk and air our grievances.

I realized I’d learned something I’d never heard from doctors during any of my dozens of trips to the STI clinic, something I’d never heard from my family, my school, in the media or from the government – that you don’t need to be afraid of people living with HIV.

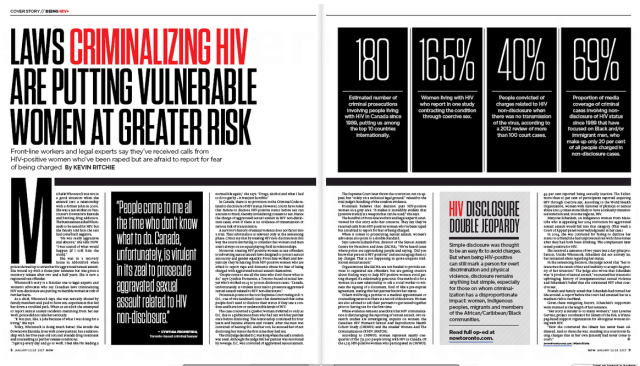

A second article, Laws criminalizing HIV are putting vulnerable women at greater risk, highlights the impact HIV criminalisation is having on women in Canada, notably that it is preventing sexual assault survivors living with HIV from coming forward due to a fear they will be prosecuted for HIV non-disclosure (which, ironically, is treated as a more serious sexual assault than rape).

A second article, Laws criminalizing HIV are putting vulnerable women at greater risk, highlights the impact HIV criminalisation is having on women in Canada, notably that it is preventing sexual assault survivors living with HIV from coming forward due to a fear they will be prosecuted for HIV non-disclosure (which, ironically, is treated as a more serious sexual assault than rape).

Moreover, treating HIV-positive women as sex offenders is subverting sexual assault laws designed to protect sexual autonomy and gender equality. Front-line workers and lawyers say they’re hearing from HIV-positive women who are afraid to report rape and domestic abuse for fear of being charged with aggravated sexual assault themselves.

“People come to me all the time who don’t know what to do,” says Cynthia Fromstein, a Toronto-based criminal lawyer who’s worked on 25 to 30 non-disclosure cases. “Canada, unfortunately, is virulent in its zeal to prosecute aggravated sexual assault related to HIV non-disclosure.”

It also features a strong editorial, ‘HIV disclosure double jeopardy’ by the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network’s Cecile Kazatchkine and HALCO’s Executive Director, Ryan Peck, which notes:

It also features a strong editorial, ‘HIV disclosure double jeopardy’ by the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network’s Cecile Kazatchkine and HALCO’s Executive Director, Ryan Peck, which notes:

In a statement that mostly flew under the radar, Minister of Justice Jody Wilson-Raybould declared, on World AIDS Day (December 1), her government’s intention “to examine the criminal justice system’s response to non-disclosure of HIV status,” recognizing that “the over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure discourages many individuals from being tested and seeking treatment, and further stigmatizes those living with HIV or AIDS.”

Wilson-Raybould also stated that “the [Canadian] criminal justice system must adapt to better reflect the current scientific evidence on the realities of this disease.”

This long-overdue statement was the first from the government of Canada on this issue since 1998, the year the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision on R v. Cuerrier, the first case to reach the high court on the subject.

Finally, the magazine features a number of promiment HIV activists from Canada, including Alex McClelland, who is studying the impact of HIV criminalisation on people accused and/or convicted in Canada.

Finally, the magazine features a number of promiment HIV activists from Canada, including Alex McClelland, who is studying the impact of HIV criminalisation on people accused and/or convicted in Canada.