Positive Lite editor Bob Leahy talks to Edwin J Bernard, co-ordinator of the HIV Justice Network, about HIV non-disclosure and the criminal law, particularly as it relates to the Canadian context where non-disclosure of known HIV-positive status prior to sex that may lead to a ‘significant risk’ of HIV transmission is considered aggravated sexual assault. The interview took place in Toronto, in May 2012, prior to the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision on the issue.

Greece: Matthew Weait on the moral panic over the mass arrest of female sex workers with HIV

Matthew Weait, Professor of Law and Policy at Birkbeck College, University of London guest blogs on Wednesday’s arrest of 17 HIV-positive women who allegedly worked illegally as sex workers. Greek authorities are accusing them of intentionally causing serious bodily harm.

The arrest in Athens of 17 female sex workers living with HIV this week is outrageous on many levels. It is not that a significant number of them have had their right to respect for private life violated (12 had their photographs published on a police website), nor that there is uncertainty as to whether the women concerned knew their HIV status, nor that the women were arrested after a screening process by the Greek Centre for Disease Control (how voluntary was that, I wonder?), nor that they have been charged with intentionally causing grievous bodily harm (a charge almost impossible to prove, and on the facts arising simply from having unprotected sex with clients – according to news reports it is unclear whether any clients have actually been infected as a result of sex with the women concerned). All these things are bad enough, but what is really appalling is the way in which it is the women who have been identified as the legitimate locus of control and the subject of punitive state response.

It is appalling, but it is entirely to be expected. There is a long and ignoble tradition of locating the source of STIs in women in general, and female sex workers in particular. In the context of HIV criminalization this tradition has reached a new peak (or, perhaps better, a new trough). Put simply, HIV criminalization has compounded, and added a new and frightening dimension to, the longstanding idea that female sex workers are a source of pollution threatening the cleanliness of men. It is not just that by identifying them as the risk and the cause of any harm men may suffer, the men concerned (and men in general) are able to divert attention from their own responsibility (though this is important), it is that criminalization has provided an opportunity, in this context, to reinforce the idea that women are inherently dirty, that HIV is dirty, and that cleansing (what a frightening word that is) through punishment, containment and deportation (the women in Athens were foreign nationals) is a reasonable and justifiable response.

Of this logic we should be very afraid. The elimination of dirt at a political level has found expression, at its most extreme, in the slaughter of the Jews by the Nazis, in the apartheid regime of South Africa, in eugenic science and rules relating to miscegenation. It is evident in any attempt by a society to maintain its ‘purity’ by imposing border controls that require would-be immigrants to undergo tests that filter out the sick and unhealthy.

At an individual level, the elimination or exclusion of dirt – or rather the practices, attitudes and response mechanisms that attempt to achieve this (prosecution, imprisonment, deportation) mirror a wider political project in which the HIV positive body is punished, marginalised and devalued because it represents everything that is feared in post-modernity. The HIV positive body is a paradigm site for repressive legal and political response because of its capacity to reproduce itself in the body of those for whom it represents a threat to physical and ontological security, and because that reproduction occurs – and can only occur – through the merging of bodies via the co-mingling of their ‘inside’. Elizabeth Grosz, an Australian feminist theorist has put this better than anyone else when she explains that:

Body fluids attest to the permeability of the body, its necessary dependence on an outside, its liability to collapse into this outside (this is what death implies), to the perilous divisions between the body’s inside and its outside. They affront a subject’s aspiration toward autonomy and self-identity. They attest to a certain irreducible ‘dirt’ or ‘disgust’, a horror of the unknown or the unspecifiable that permeates, lingers, and at times leaks out of the body, a testimony to the fraudulence or impossibility of the ‘clean’ and ‘proper’. (Grosz, 1994: 193-4)

For Grosz, it is women’s bodies, their unstable and destabilizing corporeality, that serve both to affirm men’s belief in their own inviolability and, thus, the bounded body (i.e. male bodies) as the normal, universal and legitimate form of subjectivity. The seminal flows that emit from male bodies, reduced to a by-product of sexual pleasure rather than conceived as a manifestation of immanent materiality, and as something that is directed, linear and non-reciprocal, enables men to sustain the fantasy of the closed body and of the possibility of control over it. The socio-cultural and psychological dimension of Mackinnon’s (in)famous assertion about the power necessarily instantiated in heterosexual relations (‘Man fucks woman: subject verb object’ (Mackinnon, 1982: 541), this fantasy is a prerequisite for the maintenance of masculinity, and of the mastery – over women, over nature – that masculinity enables, or which is its prerogative.

To receive flow, or to be in position where there is a risk of flow in the other direction, is to be identified with the feminine (whether as woman, or as passive homosexual) and to lose the phallic advantage; to acknowledge the essential materiality of the body, that its flows are not merely by-products of the body but constitutive of it, is an admission that strikes at the heart of masculinity, at the security which is its privilege, and at the legitimacy of the hierarchised and gendered socio-economic order upon which its privileged status depends. Understood in these terms, it is unsurprising that it is women’s bodies (despite the relatively low risk of female to male sexual transmission) that are – within the discourse that frames the heterosexual HIV epidemic– characterised as the source of infection. As Grosz explains, this discourse is one that makes

… women, in line with the conventions and practices associated with contraceptive procedures, the guardians of the sexual fluids of both men and women. Men seem to refuse to believe that their body fluids are the ‘contaminants’. It must be women who are the contaminants. Yet, paradoxically, the distinction between a ‘clean’ woman and an ‘unclean’ one does not come from any presumption about the inherent polluting properties of the self-enclosure of female sexuality, as one might presume, but is a function of the quantity, and to a lesser extent the quality, of the men she has already been with. So she is in fact regarded as a kind of sponge or conduit of other men’s ‘dirt’. (Grosz, 1994: 197)

Given Grosz’s analysis it is hardly unsurprising that the Centre for Disease Control in Greece had 1500 calls from concerned men once the story about the brothels broke. Far from accepting any responsibility they might have for having sex which carried the risk of STI and HIV infection, it was entirely to be expected that their concern was whether the women might have infected them, and that the legal response was to round up the women. Patriarchy is, after all, a Greek word.

The response of the Greek health Minister, Andreas Leverdos, prompted in part by a massive rise in HIV infections in Greece in recent months (954 new infections were reported in 2011, a 57 percent increase from the previous year), and also – surely – by the political value in deporting non-nationals at a time when Greece is in economic meltdown, was to suggest criminalizing unprotected sex in brothels. He is reported as saying,

Let’s make this a crime. It’s not all the fault of the illegally procured woman, it’s 50 percent her fault and 50 percent that of the client, perhaps more because he is paying the money.

On the face of it this response suggests some recognition of shared responsibility. However, it is a pipe-dream – I suggest – to imagine that doing this (even if it were politically viable, which I doubt) would have the effect of eradicating the deeply entrenched view that female sex workers are to blame for their clients ills; nor is criminalization of sexual behaviour that carries the risk of HIV infection a productive or constructive answer to anything. It would simply perpetuate the idea that punitive laws are an appropriate response to what is properly understood as a public health issue that should be addressed through wider awareness, education and an affirmation of the importance of taking care of, and respecting, ourselves and others.

(Reposted from Matthew Weait’s own blog, ‘The Times That Belong To Us’ with kind permission. You can also follow Matthew on Twitter @ProfWetpaint)

Norway: First gay man to be prosecuted goes public, makes a real difference (corrected)

Correction: Louis Gay tells me that he is not the first gay man to be prosecuted in Norway.

I am the first one to be prosecuted for practicing “safer sex” (oral sex, only. with no condom and no contact with sperm or precum), without transmitting any virus!

Original post: Yesterday, Bent Høie (Conservative), the leader of the Standing Committee on Health and Care Services, raised the issue of HIV in the Norwegian Parliament (Stortinget). He was concerned about the rise in new diagnoses in the country, and discussed increases in unprotected sex amongst gay men and other men who have sex with men, as well as lack of knowledge of HIV and HIV-related stigma within broader Norwegian society.

Notably, he linked these concerns with Section 155 of the Norwegian Penal Code. This infectious disease law enacted in 1902 is known as the ‘HIV paragraph’ since it has only ever been used to prosecute sexual HIV exposure or transmission. By placing the burden on HIV-positive individuals to both disclose HIV status and insist on condom use, the law essentially criminalises all unprotected sex by HIV-positive individuals even if their partner has been informed of their status, and consents. There is no distinction between penalties for HIV exposure or transmission. Both “willful” and “negligent” exposure and transmission are liable to prosecution, with a maximum prison sentence of six years for “willful” exposure or transmission and three years for “negligent” exposure or transmission.

The law is currently in the process of being revised by the so-called Syse-committee (named after its chair, Professor Syse but officially titled The Norwegian Law Commission on penal code and communicable diseases hazardous to public health), but at the moment, the current law stands. At least seventeen individuals have been prosecuted since 1999 – and until this year all prosecutions were as a result of heterosexual sex despite the fact that most HIV transmission in Norway is the result of sex between men.

Earlier this year, Norwegian prosecutors decided to prosecute the first gay man under this draconian law. Although transmission had been alleged, phylogenetic analysis ruled out Louis Gay’s virus as the source of the complainant’s infection. Still, he is being prosecuted for placing another person at risk despite the only possible risk being unprotected oral sex, and despite Louis disclosing his HIV-positive status prior to any sex (which the complainant denies).

Louis decided to go public in November 2011 during the initial police investigation. Since then he has given interviews to some of the largest circulation newspapers and magazine in Norway, as well as to national TV and radio. I had the pleasure of meeting Louis in Oslo in February when he addressed the civil society caucus that produced the Oslo Declaration.

As well as his own blog, Louis now also blogs about his experience for POZ.com. In his second post he notes that

I chose to go public before any final decision was made from the State attorney office, with the chance of provoking them to prosecute me because they don’t want to risk being criticized by media of giving in to pressure. This is fine with me. Like I’ve stated before I want to have my case tried before a court. Anyway! Now we all have to wait until the trial before we get any further answers about my case. In the meantime the discussion whether we should have a law like this (and using it like in my case) is protecting the society from more infections or just making it worse, continues.

So, yesterday, Louis’s brave stand paid off. Conservitive MP Bent Høie, the leader of the Standing Committee on Health and Care Services, mentioned Louis’ case in Stortinget.

Then it is a paradox that the social-liberal Norway still has an HIV-paragraph that is criminalizing HIV-positive people’s sexuality. This has now been brought to a head by the public prosecutor who has brought charges against HIV-positive Louis Gay, who has not infected any other person and who conducted what we call “safer sex”, which in reality is the health authorities’ recommendations. I am aware that Syse-committee is now working on this issue, but it is still necessary to highlight this in this debate, because current criminal law works against prevention strategy and stigmatize HIV-positive people. I hope that today’s debate could be the start of that we again have a strong political commitment to reducing new infections of HIV and to improve the lives of those who are HIV-positive – which in reality are two sides of the same coin.”

(Unofficial translation by Louis Gay)

I’m so impressed with Louis’s courage and determination, and I think that he actually might just be making a difference by going public. If you support Louis, let him know by leaving a comment here, or on his own blog, or at POZ.com.

US: Positive Justice Project Watching NY Court of Appeals on “Deadly Saliva” Case

Today, the New York Court of Appeals will hear the case of David Plunkett who was convicted for aggravated assault after allegedly biting a police officer during his 2006 arrest. The case rests on whether the saliva of someone with HIV can be considered a “dangerous instrument” under the law.

Lambda Legal filed a court brief earlier this week arguing that upholding Plunkett’s conviction would further stigmatise people living with HIV.

“Clearly, the trial court here erroneously believed that HIV could be transmitted by saliva,” the Lambda Legal brief reads. (Read more about the case and the entire amicus brief at Lambda Legal’s blog.)

The Positive Justice Project today released a strongly worded press release highlighting that “it’s time that courts rely on science rather than decades-old notions of HIV.” The entire release is below.

Let’s hope science wins out over stigma this time around.

New York, April 26, 2012 – Legal and public health experts are speaking out as the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in New York, today reviews a case concerning the 2006 conviction of David Plunkett, an HIV-positive man, for aggravated assault for biting a police officer. The state prosecutor argued that Plunkett used his saliva as a “dangerous instrument” when he allegedly bit a police officer during an altercation, for which he is serving a 10-year prison term.

Medical and public health experts long-ago dismissed the risk of HIV transmission through spitting or biting as near-zero, too small even to be measured.

“It is virtually impossible for HIV to be transmitted through biting,” explained Oscar Mairena, Senior Associate for Viral Hepatitis / Policy and Legislative Affairs at the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD). “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in order for there to exist even a remote possibility of transmission from a bite, there would need to be severe trauma with extensive tissue tearing and damage. What occurred in this case – and in the vast majority of HIV criminal cases that involve biting – bears no resemblance to that description.”

The Plunkett case is one of hundreds across the country where HIV-positive individuals face criminal charges and long sentences on the basis of their HIV status for no-risk conduct and consensual adult sex. Members of the Positive Justice Project, a national group challenging the medical, legal and ethical support for such laws, object to the gross scientific mischaracterizations reflected in HIV-specific criminal laws and prosecutions as “flying in the face of national efforts to get people with HIV tested and into treatment.”

“This type of case reflects widespread ignorance about the routes and actual risks of HIV transmission,” said Beirne Roose-Snyder, Managing Attorney at the Center for HIV Law and Policy (CHLP). “Persistent misinformation about how HIV is transmitted, and what it means to have HIV in 2012, is a major cause of these laws and can create a major barrier to convincing people that it is safe and necessary to get tested.

Dr. Jeff Birnbaum, Program Director of the Health and Education Alternatives for Teens (HEAT) Program and the Family, Adolescent and Children’s Experience at SUNY (FACES) Network added, “I have to battle this type of stigma with the young people I treat all the time. This kind of case just makes my job harder. It’s time that courts rely on science rather than decades-old notions of HIV.”

Dozens of U.S states and territories have laws that criminalize HIV non-disclosure and “exposure,” such as through spitting or biting. Sentences imposed on people convicted of HIV-specific offenses have ranged as high as 50 years, with many getting decades-long sentences despite lack of evidence that HIV exposure, let alone transmission, even occurred. A growing number of defendants are also being required to register as sex offenders.In New York, prosecutors have used the general criminal law to pursue people with HIV charged with HIV transmission or exposure, resulting in long prison terms despite a lack of proof that the individual charged even was the source of a partner’s infection.

“Each time there is a case like this that relies on ignorance about the nature of HIV, the public gets the message that people with HIV are highly infectious and out to hurt people,” said Michelle Lopez, community advocate and a woman living with HIV. “That message is cruel and counter-productive.”

Susan Rodriguez, also HIV-positive and Founding Director of Sisterhood Mobilized for AIDS/HIV Research & Treatment (SMART), an educational and advocacy organization for women and youth living with HIV, added, “Women and young people living with HIV pass through these doors all the time with their heads hanging down, afraid of what people will think of them because they’re positive. It can take a long time for some to believe that they have the right to hold their heads high, because they have a virus, not a character defect or a loaded gun. Telling people to get tested on one hand, and then turning around and treating them like felons? Do they really think that telling people who test positive that they are dangerous will encourage others to get tested, let alone to disclose their status to someone who can get them thrown in jail? Be real.”

Sweden: Latest HIV non-disclosure prosecution highlights why Sweden’s “nanny state” is getting it so wrong

Last week a 31-year-old woman, previously found guilty of attempted aggravated assault for having unprotected sex with her male partner without disclosing her HIV-positive status, was sentenced by the Falun District Court to 18 months in prison. The man has not tested HIV-positive.

An editorial by the ubiquitous Professor Matthew Weait in today’s Newsmill (‘Rädsla för det orena bakom Sveriges hårda hiv-lagar’ / ‘Fear of the unclean behind Sweden’s harsh HIV laws’) critiques such prosecutions as symptomatic of Sweden’s “nanny state” approach to the lives of its citizens.

So far, of the eleven comments, only one appears to agree with Matthew’s brilliant but challenging assessment. Fortunately, it is not necessarily the general public in Sweden that needs to be persuaded to change course, but Sweden’s politicians. In this regard, the editorial may be helpful to the two year campaign by RFSU (the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education), HIV-Sweden, and RFSL (the Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights) to raise awareness and advocate against overly draconian HIV criminalisation in Sweden.

Here’s the original English version adapted from Matthew’s blog.

There is a horror film from 1992 called “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle”. The plot centres on the efforts of a vengeful nanny to destroy the life of a woman who the nanny blames for her own husband’s suicide and the miscarriage she subsequently suffers. The title is a good one for the film because it suggests security and safety when the opposite is in fact the case. There is nothing more disturbing than discovering that the person in whom you have put your trust is in fact the source of danger and harm to the thing you hold most dear.

Sweden has rocked its children in a cradle handed down through the generations for over a century, carved from the warm, soft wood of social democracy. And, for most of the children, the cradle is a very safe place. Indeed, many have fallen asleep as she rocks them and find the constant motion so comforting that there is little desire to wake up (which suits nanny just fine). For some other children though, the story is very different. Beware those who refuse to believe all of the stories nanny tells them, or the children behaving in such a way that she thinks will set a bad example. It’s not that she wants to be cruel, but she knows what’s in their best interests. She has little, if any, tolerance for those who jeopardise all the work she has done in raising the good, obedient, children, and she will take almost any action necessary to show the bad ones the error of their ways and bring them into line. Tough love: that’s nanny’s motto.

Some readers may find this extended metaphor shocking. It is meant to be. I, like many of my contemporaries in countries with less welfare-oriented, and stronger liberal-conservative, political traditions have always thought of Sweden and its neighbours as some kind of Nirvana – a promised land in which no-one will ever be too rich, and no-one too poor; where the contract between state and citizen assures security and support for all, irrespective of the personal misfortunes and disadvantages people may experience.

My recent research into Sweden’s response to people living with HIV has demonstrated how this image – accurate in many respects – is only part of the story. Not only has Sweden detained more than 100 people under its communicable disease legislation since the epidemic began (and been held, in one case, to have violated the European Convention on Human Rights as a result), it criminalises more people per 1000 living with HIV (PLHIV) than any other country in Europe. It criminalises them not only for deliberate transmission, but for non-deliberate transmission and for exposure (where HIV is not in fact transmitted). It criminalises only those who know their HIV status, despite the fact that the source of most new infections is people who are undiagnosed, and ignores the fact that PLHIV on effective treatment and with an undetectable viral load present practically no risk of onward transmission to a partner during sex. It criminalises these people despite the fact that HIV is a public health issue, despite the fact that there exists no evidence that criminalisation has any public health benefits, and despite the fact that the sensationalist headlines which accompany stories about HIV cases contribute to and reinforce the stigmatisation of all PLHIV.

It is my strong belief is that Sweden’s coercive and punitive response to HIV has its source precisely – and paradoxically – in values that have become so embedded in the psyche of the general population over the past century that anything, or anyone, that threatens them is treated as a dangerous contaminant to be dealt with accordingly. Just as with its approach to sex work (even this term is disliked), which treats all workers as victims and all men as deviant criminals, and drug use (where harm reduction – despite its efficacy – is distrusted because it suggests tolerance of something essentially dirty and dangerous), HIV is criminalised because it threatens, at a very fundamental level, what being Swedish means. HIV is not clean. HIV is not healthy. HIV is not normal. For as long as HIV can be contained among men who have sex with men, drug users and migrants – and (critically) be seen to be contained there by everyone who is not a member of these groups – the Swedish self-image of a country committed to enlightened, progressive values can be sustained. And because this is so important, any measures – however repressive, illogical or misguided – are acceptable.

Since March 2012, Sweden has a new Ambassador to the Kingdom of Swaziland, Ulla Andrén. On presenting her letters of credence to the King, Ambassador Andrén emphasised “the importance of a continued effort to work against the HIV/AIDS pandemic” in that country. Swaziland has the highest HIV prevalence in the world, with more than one in four people living with virus (some 200,000 people). Given the passionate commitment it has demonstrated to punishing PLHIV domestically, and its belief in the value of a punitive response, it would seem only sensible that Sweden should suggest that Swaziland adopts its. Except of course it shouldn’t do this, and nor would it. But it’s a serious point though. If it would be wrong to recommend the criminalisation of HIV in Swaziland, where HIV remains, for many, a dangerous and deadly disease, then why is it OK to criminalise it at home, where people who are diagnosed can lead long and otherwise healthy lives?

We all understand why the children like sleeping in nanny Sweden’s cradle. But it might be interesting, and liberating, for them to wake up and test her patience a little …

Norway: Prof. Matthew Weait delivers stirring clarion call to recognise harm of HIV criminalisation

Yesterday Professor Matthew Weait, Professor of Law and Policy at Birkbeck College, University of London delivered a stirring lecture to the public health professionals involved in implementing Norway’s HIV strategy. As Norway is currently reconsidering its criminal code as it relates to HIV and other infectious diseases, ‘Criminalisation and Effective HIV Response’ was a clear clarion call to “recognise that HIV is not a legal problem capable of a legal solution, but a public health issue to be dealt with as such.”

What I would urge you to recognise is that the appeals for change are being made not only by people living with HIV and the civil society organisations advocating on their behalf, but increasingly by health professionals, virologists, epidemiologists and others who have come to recognise that punitive responses to HIV are counter-productive and damaging in efforts to respond effectively to the spread of the virus. This is a critically important point, and their voice needs to be heard.

With Matthew’s permission, I am publishing the entire lecture below. You can also download the full text (with full detailed footnotes and references) from Matthew’s blog.

|

| Courtesy of Charlotte Nördstrom |

As a country which many in the world look to for progressive policy-making grounded in evidence and human rights principles, Norway’s response to HIV is not simply a matter of national importance, but is of significance both to the developing countries to which it provides economic and other assistance in the fight against endemic HIV, and to high-income countries whose epidemics are similarly limited and concentrated in particular population groups.

Your current national strategy – Acceptance and Coping – states as follows:

The comprehensive aim of this strategy is that at the end of the strategy period, Norway will be a society that accepts and copes with HIV in a way that both limits new infection and gives persons living with HIV good conditions for social inclusion in all phases of their lives.

The strategy document sets out a number of specific goals, each of which discusses measures that will be taken in order to deliver on the strategy. My focus today is on the way criminalisation of HIV transmission and exposure might impact on that strategy. I will start, though, with some background and context.

1. International Thinking and National Law

At the 26th special session of the UN General Assembly in 2001, States party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural rights (including Norway) declared their commitment to

… enact, strengthen or enforce, as appropriate, legislation, regulations and other measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination against and to ensure the full enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by people living with HIV/AIDS and members of vulnerable groups …

This commitment is yet to be realised. Since the beginning of the epidemic new and existing legislative measures have been introduced and enforced that impede rather than further the central goal of reducing onward transmission of HIV, of minimising the spread of the epidemic, and protecting the rights of PLHIV and those most at risk of infection.

In a 2010 Report, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health referred to this commitment in the context of the criminalisation of HIV transmission and exposure. Drawing on the best available evidence he emphasised that criminalisation has not been shown to limit the spread of HIV, that it undermines public health efforts and has a disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities.

Drawing on the UNAIDS International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights and more recent UNAIDS/UNDP policy, he reiterated that the criminal law should only be deployed in very limited circumstances. In particular, people should not be prosecuted where there is no significant risk of transmission, where they are unaware of their HIV positive status, do not understand how HIV is transmitted, have disclosed their status (or honestly believe their partner to know it), failed to disclose because of a fear of violence or other serious negative consequences, took reasonable precautions against transmission, or have agreed on a level of mutually acceptable risk.

Norway, in common with most other countries, falls significantly short of the UNAIDS guidance and of the Special Rapporteur’s recommendations. Its current criminal law imposes liability irrespective of a person’s viral load, those who transmit HIV non-intentionally, and on those who merely expose others to the risk of infection. Also, and more exceptionally, it allows for the criminalisation and punishment of those who engage in unprotected sex, even when they have disclosed their HIV positive status to their partner and where the partner has consented to the risk of transmission. Although its penal code allows for the criminalisation of other serious diseases, almost all cases that have been brought to the courts have concerned HIV – and so although it is not an HIV-specific law in theory, the practice is very different.

2. The Enforcement of Law

This use of the criminal law has placed Norway – along with its Scandinavian and Nordic neighbours, at the top of the leader board of HIV criminalisation in Europe, and very high globally. When we look at rate of convictions per 1000 PLHIV in the European region, we see a higher rate of conviction in northern European countries, especially those in Nordic and Scandinavian countries.

This variation in intensity of criminalization as measured by convictions seems strange at first glance, especially when you contrast it with the HIV prevalence estimates.

It is especially notable that the bottom three countries with respect to criminalisation (Italy, France, UK) have – conversely – the highest numbers of people living with HIV, and (in general) higher than average prevalence.

What, then, might be explanations for this? We have to be cautious, given the non-systematic nature of the data collection; but I do think that we can begin to understand the pattern if we think about some of the social, cultural and historical differences between countries in the region.

So, for example, we can see that the top five criminalising countries in the region all have laws which impose liability for the reckless or negligent exposure (and thus have a wider potential scope for criminalisation). We can also see that these same countries all have high confidence in their judicial systems (which may go some way towards accounting for a person’s willingness to prosecute after a diagnosis, believing that their complaint will be dealt with efficiently and fairly). Even more interestingly, I think, are the correlations that we see when we look at variations in interpersonal trust, as measured by the World Values Survey.

Here we can see the top five countries in the region with respect to interpersonal trust (and the only countries where the majority of respondents trusted other people), are all in the top half of criminalizing countries, with rates of conviction in excess of 1 / 1000 PLHIV.

These correlations between interpersonal trust and conviction rates in the region become even more interesting when we learn that, according to reliable empirical research, the Scandinavian and Nordic countries have a lower fear of crime, are less punitive in their attitudes to those who commit crime, and – in general – have lower rates of imprisonment for convicted offenders than other countries. If this is the case, why would HIV transmission and exposure criminalization be so high?

My answer to this is tentative, but it seems plausible to suggest that the sexual HIV cases that get as far as court and a conviction are ones which are paradigm examples of breach of trust. It is not inconsistent for a society to have a lower than average generalised fear of crime, or lower than average punitive attitudes, and at the same time to respond punitively to specific experiences of harm, especially when that arises from a belief that the person behaving harmfully could have behaved otherwise and chose not to. Indeed, it seems entirely plausible that where there are high expectations of trust, breaches of trust (for example, non-disclosure of HIV status) are treated as more significant than where value in trust is low. Combine this with countries (such as your own and Sweden) which are committed to using law to ensure public health, and which consequently are prepared to using it to respond to the risk of harm (HIV exposure), as well as harm itself (HIV transmission), and we can see why the pattern of criminalization appears to be as it is.

3. Impact of Criminalisation on PLHIV and Most at Risk Populations

What is the impact of criminalisation?

This is a difficult question to answer, because it depends on what we mean by impact. First, there is the impact on the individual people who have been, and continue to be, prosecuted – people who have been investigated, convicted, jailed and publicly shamed, sometimes simply for having put others at risk, sometimes for transmitting HIV unintentionally, sometimes when they have been completely open about their status with a partner in a relationship which subsequently breaks down. For these people, being HIV positive and failing to live up to the exacting standards the law in this country, and others in this region, demands of them has turned them into criminals with all the social and economic disadvantages that entails. Here we could think specifically of your own fellow country man Louis, who had a charge of transmission dropped when it transpired that he was not the source of his partner’s infection, but is still being prosecuted for exposure.

Second, and critically, there is the impact on public attitudes towards, and responsibility as regards HIV, PLHIV and sexual health generally. Here I am not talking just about the individual experience of the two Thai women in Bergen who stopped in a bar for a drink after shopping and, in front of other customers, were thrown out by the owner because of a recent case in the town involving a Thai sex worker (from that point on, being Thai themselves (though legally in the country and married to Norwegian men) made them guilty, positive and dangerous simply by association). I am talking more of the broader impact that such an example illustrates.

Criminalisation, because it places responsibility for transmission risk on people with diagnosed HIV, serves to reinforce the idea that responsibility for one’s own sexual health belongs with those people. The existence of criminal law provides people who have consciously taken risks with an official mechanism for declaring their victim status. It provides grown, adult, men who have unprotected sex with migrant sex workers an opportunity to deny any responsibility they might have for actually taking responsibility themselves. It provides people (in Norway) who in fact consent to sex with a person who has disclosed his or her positive status the opportunity to take revenge if the relationship breaks down. If we can blame someone else for misfortune, or for being in situations where there is a risk of harm, it is only natural that some of us will; and the sensationalist media coverage (as bad here as it is anywhere in the world) merely serves to confirm this and to sustain the ignorance which the FAFO study highlighted. The headlines are, as you well know, always in the form “HIV-man (or woman) exposes x number of women (or men) to HIV.” They are never in the form “X number of people put themselves at risk by having unprotected sex”.

Finally, I would just like to mention Maria (not her real name) who I interviewed here in Oslo in March 2012. For her, a mother of two children who was contacted by the police about the arrest of a man she had had a sexual relationship with (but who was not in fact the source of her HIV infection) the trial in which she was made to be a complainant has resulted in her being so afraid of legal repercussions that she has not had sex for eighteen months. For Maria, and people like her, a guilty verdict does not necessarily result in closure, and it does not result in a reversal of sero-status. It simply creates another potential criminal who better beware. If, as Acceptance and Coping states, Norway is serious about reducing the number of new infections, enabling people to feel secure in testing and in discussing their positive status more openly, it must recognise that criminalisation of the kind that exists in this country does nothing to assist in those endeavours.

4. Barriers to Change

What, then, are the barriers to change? I ask this question recognising that the Commission led by Professor Aslak Syse has yet to report on its findings and make recommendations, and here I will mention only two.

The first thing I would say here is that here are many in the Scandinavian and Nordic region who are calling for a change in the law. However, there has been, and continues to be, among politicians and policy makers – as well as among some public health professionals – a scepticism about calls to decriminalise non-deliberate HIV transmission and exposure.

Take politicians first. Their scepticism stems, I think, from a belief that arguments in favour of decriminalisation when made by advocacy organisations are – in effect – arguments for being allowed to practise unsafe sex with impunity: without consequence. If a gay man living with HIV argues that he should not be punished if he has unprotected sex, or does not disclose his status to a partner, or happens to transmit HIV during consensual sex (even when this is the last thing he wishes to do) it is very easy to hear that as someone claiming a right to be irresponsible. Put simply, the fact that at a national level in this region the decriminalisation advocacy work has been pursued largely – though not entirely – by civil society organisations has resulted in a less than sympathetic response from those in a position to deliver change – especially those elected politicians whose principal concern is their immediate electorate and public opinion more generally. Nor, for a long time, has the medical profession been entirely supportive. For doctors, especially those in official public health positions at national and regional level, it has been problematic to support those who seem to wish to challenge their role in protecting the health of society generally. For health professionals, arguments for repealing the coercive powers given to them under communicable disease legislation, or of the criminal law that provides the final sanction against those who do not comply with regulations, are easily read as arguments for allowing people with HIV the right to undermine the very thing it is their responsibility to achieve: as a right to put healthy people at risk of disease and illness.

Faced with the way in which their arguments have been interpreted by those with political power, it is small wonder that those appealing for change have met with limited success, despite arguments consistent with those of expert international organisations (such as UNAIDS). What I would urge you to recognise is that the appeals for change are being made not only by people living with HIV and the civil society organisations advocating on their behalf, but increasingly by health professionals, virologists, epidemiologists and others who have come to recognise that punitive responses to HIV are counter-productive and damaging in efforts to respond effectively to the spread of the virus. This is a critically important point, and their voice needs to be heard.

The second factor that sustains the legitimacy of punitive laws in a country, and makes their reform difficult, is the nature of the epidemic in that country. Like other Nordic countries, Norway’s HIV epidemic is localised both socially and geographically. It is predominantly an urban disease affecting MSM and migrants from high-prevalence regions in Africa and Asia. Recognition of this has led to targeted prevention strategies, which is of course welcome; but it has also contributed to the ignorance about HIV among the general population (as shown by the FAFO study), and – critically, I think – to a perception that HIV is, and remains, someone else’s problem. Epidemiologically this may be correct. HIV does not, in general, impact directly on the lives of the vast majority of Norwegians. Few will know someone living with HIV, and even fewer someone who is open about his or her positive status. A consequence of this is that measures which would be seen as gross infringements of civil liberties and personal freedom if applied to the general population are seen as a reasonable and legitimate response. It is as if HIV were a snake that has found its way into a party full of animal rights activists. They cannot simply kill it (that would be wrong, and there are some limits to how one may reasonably respond to phobias) but it is justifiable to take any containment measures necessary to stop it getting any closer.

If you doubt this, consider the following two questions. First, we know that a significant number of new transmissions of HIV are from those who are newly infected and undiagnosed. If the criminal law on exposure and transmission were logical, should it not be applied to all those who have unprotected sex with a partner, who have had unprotected sex in the past, and who do not have a recent negative test result? And if we think non-disclosure is a justification for criminal liability, should we not criminalise all those who fail to disclose the fact that they have had unprotected sex in the past and are uncertain of their HIV status? Being HIV positive is not the relevant risk: infectiousness is.

Why don’t we do that when it is the logical approach? Because such rules would apply to the vast majority of adults in Norway, not merely to a containable and definable sub-section of those adults. And even those who might respond to this proposition by pointing out that undiagnosed HIV is far more common among MSM and migrants would have a hard time justifying criminalising all unprotected homosexual (but not heterosexual) sexual activity, and the unprotected sexual activity of migrant people from high-prevalence regions with native Norwegians. This would be seen, I suspect, as a grossly discriminatory and offensive approach – despite the fact that it makes far more sense than the one that you have here.

As to the second question, consider this. Norway, in common with its neighbours, has a strong tradition of overseas aid, and an official, publicised commitment to providing assistance to developing countries in their fight against HIV and AIDS. Indeed, the Government of Norway has publicly stated that it “ … wishes to focus on how legislation and public services can do more to reduce vulnerability and increase dignity and better cooperation into the fight against AIDS”.

The question therefore is: should Norway encourage the high-prevalence countries to which it provides support to adopt its legal model their HIV response? Put simply, do you think it would be appropriate to criminalise HIV transmission, exposure and non-disclosure where it is endemic? My guess is that your answer to that would be no. But if the answer is no, you must ask yourselves – as matter of fundamental ethics – why not? Why is it appropriate to respond punitively to PLHIV living in Norway when to do so in Botswana, or Malawi, or Swaziland would be wrong?

It seems to me that the answer to this question, even if it is a difficult and uncomfortable one to acknowledge, is that for as long as HIV only affects a small and definable minority punishment is defensible. As long it is “over there”, among the gays and the migrants and the IDUs, and for as long as coercive powers will not impact on the vast majority of the population, criminalisation is something that can be legitimated and politically defended without fear of popular protest. If this is correct, it is particularly offensive and pernicious. Exposure is exposure wherever it takes place in the world; transmission is transmission; HIV is HIV; disclosure is either to be required as a matter of principle, or not. If criminalisation is not something that one country would countenance for human beings in countries in which HIV continues to be a real and immanent threat, and – critically – human beings for whom HIV infection is far less easy to manage, and still results in significant mortality, then on what possible principled basis is it justifiable to use the criminal law against those in one’s own country, where HIV is a manageable condition and where the quality of life for diagnosed PLHIV is as high as it possibly could be? If there is any substance to the claim that the legal response to PLHIV in Norway is discriminatory – which many of its critics suggest – that substance finds its expression here.

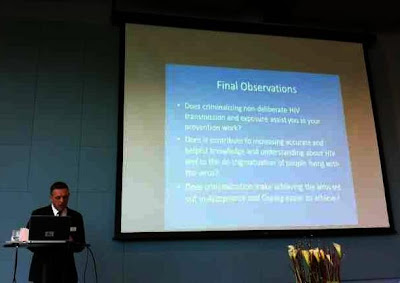

5. Final Observations

Norway is placed better than any other nation at the present moment to reform its law so that it complies with UNAIDS recommendations. The work of the Law Commission, which will report in the autumn of 2012, has been more focused and comprehensive than any other initiative I know of. Its report will, I have no doubt, present arguments both for and against the present law, and those arguments will be supported by the best available evidence. Ultimately, though, legal reform is in the hands of politicians, and their concerns extend beyond the logic of prevention. What those politicians need is the support of those who work in the field, at the sharp end of HIV prevention, diagnosis and treatment. Without that, it will be all too easy to adopt minimal reforms that do not go to the heart of the matter, or to kick the report into the long grass and carry on as before. It is not for me to tell you what your law should be. All I can do is urge you to read the Oslo Declaration, published here just recently, and to watch the video accompanying that. All I can do is encourage you to recognise that the authors of the HIV Manifesto, a radical initiative demanding the repeal of paragraph 155 of the Penal Code, was not written by people who simply want to have sex without consequences but by intelligent, rational and thoughtful people. All I can ask you to do is to recognise that HIV is not a legal problem capable of a legal solution, but a public health issue to be dealt with as such. All I can suggest is that in thinking about this complex topic you ask yourself the following simple questions.

Does criminalising non-deliberate HIV transmission and exposure assist you in your prevention work?

Does it contribute to increasing accurate and helpful knowledge and understanding about HIV and to the de-stigmatisation of people living with the virus?

And does criminalisation make achieving the aims set out in Acceptance and Coping easier to achieve?

If the answer to any or all of these questions is no, then the arguments for HIV criminalisation of the kind and intensity that currently exist in this country are not, I would suggest, as strong as those against.

Switzerland: New Law on Epidemics only criminalising intentional transmission passed in lower house

In a remarkable turns of events in the Swiss Federal Assembly’s National Council (lower house) yesterday, the new, revised Law on Epidemics was passed with a last minute amendment by Green MP Alec von Graffenried that only criminalises the intentional spread of a communicable disease.

The history of the revision of the Swiss Law on Epidemics has been a long and rocky one. The redrafting of revisions to Article 231 of the Swiss Penal Code – one of the most draconian and discriminatory laws on HIV exposure in the world – began in 2010.

The first draft of the proposed new article removed much of the most draconian provisions (i.e. allowing for prosecutions of an HIV-positive partner despite an HIV-negative partner’s full, knowing consent to unprotected sex) leaving only intentional exposure or transmission a criminal offence. Broad stakeholder consultation agreed with this draft.

However, in December 2010, a new draft presented by the Swiss Parliament’s Executive Branch (Federal Council) ignored the consultation and added lesser states of mind – simple intention and negligence – as well as malicious intent, despite the broad acceptance that the previous version had achieved amongst all stakeholders. Furthermore, the bill introduced a new paragraph creating an HIV disclosure defence.

At a mid-2011 hearing, the National Council’s Committee on Social Security and Public Health (tasked with the re-drafting of the Law on Epidemics) appeared to be open to moving back towards the original draft. The Committee explicitly recognised that the present criminalisation of consensual unprotected sex between a person with HIV and one without undermines prevention efforts and the principle of shared responsibility of both sexual partners.

However, at the end of 2011 the Committee produced further amendments that discarded the disclosure defence but which added “lack of scruples” and “self-serving motives” as alternative elements of intent. The Committee remained split on the question of negligence with the majority opting to retain the section and the minority recommending it be stricken.

So it came as a very welcome surprise that, when the bill finally reached the National Council for debate and final vote yesterday, an amendment by Green MP Alec von Graffenried was proposed at the last minute and almost immediately and overwhelmingly passed by 116 votes to 40.

A transcript of the entire proceedings (in a combination of French and German) are available here, but below I quote the full (unofficial) English translation of von Graffenried’s speech (courtesy of Nick Feustel) explaining his amendment.

In short, he says that the Law on Epidemics needs to deal only with public health issues, such as bioterrorism, and not address harm to individuals. He notes that general assault laws already exist to punish egregious cases of HIV transmission and that much of the proposed bill is not only redundant, but confusing. “You can’t be ‘negligent’, ‘malicious’ and ‘unscrupulous’ at the same time, that’s just not logical,” he argued, quite convicingly.

Advocates in Switzerland were overjoyed at this unexpected turn of events, but one government insider warns that we should not celebrate too early. The bill must now go through the Health Commission of the Council of States (upper house), before it goes to a final vote, and this could take some time (June is mooted, but not definite) and so there may still be further amendments.

For now, however, the clear logic and rationality of von Graffenried is to be celebrated.

Hopefully these developments will have an impact on other countries, too, notably Norway where a similar commission is debating changes to laws that are eerily similar in purpose and outcome to Switzerland’s notorious and outdated Article 231.

Von Graffenried’s Speech

“I speak for the parliamentary group of the Green Party, but of course also in part for my proposition as an individual. This is about punitive laws, we are talking about the amendment of Article 231 in the Penal Code. Reading the draft doesn’t really make you understand what the Commission was about. So I stopped short and then tried to make it clearer in my proposition. As Mrs Schenker explained earlier, there were still some unanswered questions after the Commission’s consultation.

“The problem is that when it comes to transmission of diseases there are always two levels. On the one hand, there is the individual level, the individual health of the aggrieved party. Their health and physical integrity are protected by Articles 111 and the following on those offenses at the beginning of the Special Section of the Penal Code. On the other hand, there is the disease-control part of it. This is the part that article 231 is meant to deal with. That was – how I learned from conversations with the Commission’s members – the Commission’s concern. Article 231 in its present form confuses these two levels. That is how, until now, for example an HIV positive person becomes guilty of bodily harm according to article 123 as well as the spreading of human diseases according to article 231.

“In their draft, the Federal Council completely revised article 231. They included a ‘basic offense’, a ‘qualified offense’, a ‘privileged offense’ and a ‘negligent offense’. But they still adhered to article 231 protecting individual health as well as being effective for disease-control. This was obviously not what the Commission wanted, and so they slashed the article.

“Obviously, the Commission didn’t want to adopt this concept. They only wanted to adopt the ‘qualified offense’, i.e. a highly criminal, if not even terroristic offense. This is about public health, i.e. the spreading of epidemics. This is what I adopted for my proposition. Possible intentional or negligent bodily harm or even manslaughter are covered by the regulations in Article 111 and the following of the Penal Code. Those are about individual health. Thus, criminal liability is only carried out under these regulations, but not anymore under Article 231 of the Penal Code on the spreading of human diseases.

“However, the Commission adopted the ‘negligent offense’. I’ll have to expatiate on this.

“The negligent perpetration is already regulated under the Administrative Criminal Law. Having an article in the Penal Code on this is unnecessary, because this regulation is already included in Articles 82 and the following of the Epidemics Law, which you have just enacted without discussion. Negligent perpetration is already included there.

“The Commission’s version is not possible, because the Commission eliminated the ‘basic offense’. You can’t be ‘negligent’, ‘malicious’ and ‘unscrupulous’ at the same time, that’s just not logical. Paragraph 2 would become ineffective, but at the same time it would also prevent the application of the Administrative Criminal Law, because Article 82, paragraph 1 excludes applying the Administrative Criminal Law, because the Penal Code does have this regulation.

“Therefore, I ask you in the name of the parliamentary group of the Green Party to accept my proposition as an individual, in order to clarify the punitive laws.”

International civil society experts launch the Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation

A group of 20 expert individuals and organisations from civil society around the world working to end inappropriate criminal prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, potential exposure and non-intentional transmission from around the world came together in Oslo, Norway on 13 February 2012 to create the Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation.

The Declaration provides a clear roadmap for policymakers and criminal justice system actors to ensure a linked, cohesive, evidence-informed approach to produce a restrained, proportionate and appropriate use of the criminal law, if any, to cases of HIV non-disclosure, potential exposure and non-intentional transmission.

It is a direct response to the increasing numbers of people living with HIV who are being arrested, prosecuted and convicted and the rapid rise in the number of countries enforcing, enacting or proposing HIV-specific legislation to enable these prosecutions. This, despite a growing body of evidence suggesting that the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, potential exposure and non-intentional transmission is doing more harm than good in terms of its impact on public health and human rights.

The civil society meeting took place on the eve of the global High Level Policy Consultation on the Science and Law of the Criminalisation of HIV Non-disclosure, Exposure and Transmission, convened by the Government of Norway and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The objective of the High Level Policy Consultation was to provide a global forum in which policymakers and other concerned stakeholders could consider their current laws and policies regarding the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission in light of the most recent and relevant scientific, medical, public health and legal data.

Although the Oslo Declaration is not an official High Level Policy Consultation document, it supports the objective of the meeting, and encourages policymakers to review their own laws and policies, and to take any and all steps necessary to achieve the best possible outcomes in terms of justice and protection of public health in order to support effective national responses to HIV and uphold international human rights obligations.

The Declaration’s creation is led by, and includes, people living with HIV, including survivors of HIV criminalisation, and supported by committed HIV advocates from all over the world. Their expertise covers medical, social, ethical, political, human rights and judicial issues relating to HIV and the criminal law.

The Oslo Declaration, the full version of which can be downloaded here (and which includes full references to support the statements), consists of the following 10 points:

1. A growing body of evidence suggests that the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, potential exposure and non-intentional transmission is doing more harm than good in terms of its impact on public health and human rights.

2. A better alternative to the use of the criminal law are measures that create an environment that enables people to seek testing, support and timely treatment, and to safely disclose their HIV status.

3. Although there may be a limited role for criminal law in rare cases in which people transmit HIV with malicious intent, we prefer to see people living with HIV supported and empowered from the moment of diagnosis, so that even these rare cases may be prevented. This requires a non-punitive, non-criminal HIV prevention approach centred within communities, where expertise about, and understanding of, HIV issues is best found.

4. Existing HIV-specific criminal laws should be repealed, in accordance with UNAIDS recommendations. If, following a thorough evidence-informed national review, HIV-related prosecutions are still deemed to be necessary they should be based on principles of proportionality, foreseeability, intent, causality and non-discrimination; informed by the most-up-to-date HIV-related science and medical information; harm-based, rather than risk-of-harm based; and be consistent with both public health goals and international human rights obligations.

5. Where the general law can be, or is being, used for HIV-related prosecutions, the exact nature of the rights and responsibilities of people living with HIV under the law should be clarified, ideally through prosecutorial and police guidelines, produced in consultation with all key stakeholders, to ensure that police investigations are appropriate and to ensure that people with HIV have adequate access to justice.

We respectfully ask Ministries of Health and Justice and other relevant policymakers and criminal justice system actors to also take into account the following in any consideration about whether or not to use criminal law in HIV-related cases:

6. HIV epidemics are driven by undiagnosed HIV infections, not by people who know their HIV-positive status. Unprotected sex includes risking many possible eventualities – positive and negative – including the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections such as HIV. Due to the high number of undiagnosed infections, relying on disclosure to protect oneself – and prosecuting people for non-disclosure – can and does lead to a false sense of security.

7. HIV is just one of many sexually transmitted or communicable diseases that can cause long-term harm. Singling out HIV with specific laws or prosecutions further stigmatises people living with and affected by HIV. HIV-related stigma is the greatest barrier to testing, treatment uptake, disclosure and a country’s success in “getting to zero new infections, AIDS-related deaths and zero discrimination”.

8. Criminal laws do not change behaviour rooted in complex social issues, especially behaviour that is based on desire and impacted by HIV-related stigma. Such behaviour is changed by counselling and support for people living with HIV that aims to achieve health, dignity and empowerment.

9. Neither the criminal justice system nor the media are currently well-equipped to deal with HIV-related criminal cases. Relevant authorities should ensure adequate HIV-related training for police, prosecutors, defence lawyers, judges, juries and the media.

10. Once a person’s HIV status has been involuntarily disclosed in the media, it will always be available through an internet search. People accused of HIV-related ‘crimes’ for which they are not (or should not be found) guilty have a right to privacy. There is no public health benefit in identifying such individuals in the media; if previous partners need to be informed for public health purposes, ethical and confidential partner notification protocols should be followed.

The 20 original endorsing individuals/organisations are (in alphabetial order)

AIDS Fondet, Denmark

AIDS Fonds, Netherlands

AIDS & Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA), Namibia

Edwin J Bernard, HIV Justice Network, UK/Germany

Center for HIV Law and Policy, United States

Kim Fangen, HIV Manifesto, Norway

Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+),Netherlands

Groupe sida Genève, Switzerland

HIV Finland, Finland

HIV Nordic, Nordic countries

HIV Norway, Norway

HIV Sweden,Sweden

International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), United Kingdom

Ralf Jürgens, Consultant, HIV/AIDS, health, policy and human rights, Canada

Sean Strub, SERO Project, United States

Robert Suttle, SERO Project, United States

Swedish Association for Sexuality Education, (RFSU), Sweden

Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights (RFSL), Sweden

Terrence Higgins Trust, (THT), United Kingdom

Matthew Weait, Professor of Law and Policy, United Kingdom

To find out more or to sign on to the Oslo Declaration please visit: hivjustice.net/oslo.

High Level Policy Consultation on HIV Non-Disclosure, Exposure and Transmission (Oslo, Norway, 2012)

At the UNAIDS high level policy consultation on HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission meeting in Oslo, Norway on February 14, 2012, UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé was characteristically frank in his comments prior to viewing Sean Strub’s short film, HIV is Not a Crime, and hearing comments from Robert Suttle (who is featured in the film).

Video courtesy of Sean Strub and filmed by Nicholas Feustel (georgetownmedia.de). Read more about the meeting in Sean’s blog at Poz Magazine.

Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation (HJN, 2012)

Advocates working to end inappropriate criminal prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, potential exposure and non-intentional transmission from around the world explain why they support the Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation.

Video produced for the HIV Justice Network by Nick Feustel, georgetown media.