The new website for the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE (HJWW) coalition is now online, in four languages – English, French, Russian, and Spanish.

HJWW is an international coalition working to shape the discourse on HIV criminalisation, as well as share information and resources, network, build capacity, mobilise advocacy, and cultivate a community of transparency and collaboration.

The HIV Justice Network serves as the secretariat, co-ordinating a global work plan; monitoring laws, prosecutions, and advocacy; providing tools and training for effective advocacy and communications; and connecting and convening a diverse range of stakeholders. With this structure, each coalition member can achieve more mission-aligned impact through their engagement in HJWW.

HJWW was founded in March 2016 during a meeting in Brighton, UK, that was funded by a grant from the Robert Carr Fund. Since then, we have expanded from seven founding partners to our current fourteen coalition members, with more than 130 organisational supporters from around the world. You can see our collective impact by visiting the Milestones page.

The new website – optimised for mobile screens as well as computers and tablets – reflects the work of our expanded coalition. It also provides information and links to websites and key resources explaining what HIV criminalisation is, why we care so much about it, and how you can stay informed and show your support.

Visit and share the new website today. After all, we won’t end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, or end HIV-related stigma, discrimination and criminalisation without HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE!

IAS 2023: Five-year impact of Expert Consensus Statement – poster published today

Today, 24th July, at the 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science on Brisbane, we presented our research findings on the five-year impact of the ‘Expert Consensus Statement on the Science of HIV in the Context of Criminal Law’.

Click on the image above to download the pdf of the poster

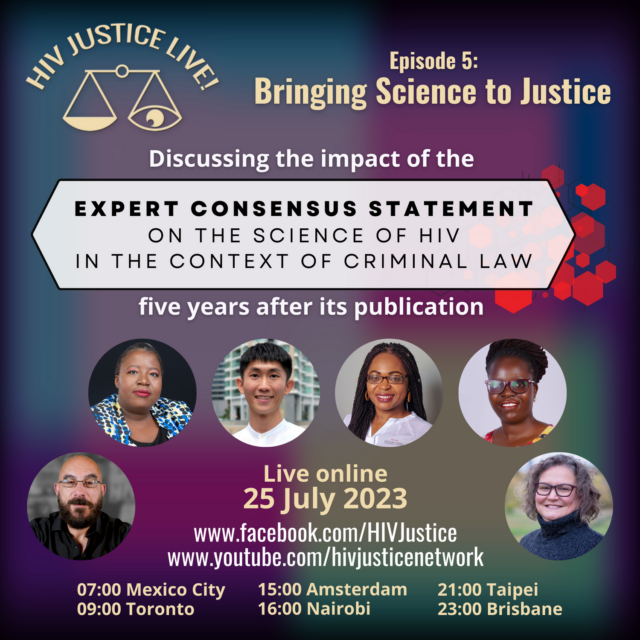

Tomorrow, 25th July, we will publish the full research report and discuss the findings on our live webshow, HIV Justice Live!

Hosted by HJN’s Executive Director, Edwin J Bernard, the show will include a discussion with the report’s lead author, HJN’s Senior Policy Analyst Alison Symington, as well as interviews with Malawian judge Zione Ntaba, Taiwan activist Fletcher Chui, and SALC lawyer Tambudzai Gonese-Manjonjo on the Statement’s impact.

We’ll also hear from some of the Expert Consensus Statement’s authors, including Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, Salim S Abdool Karim, Linda-Gail Bekker, Chris Beyrer, Adeeba Kamarulzaman, Benjamin Young, and Peter Godfrey-Faussett.

Ugandan lawyer and HJN Supervisory Board member Immaculate Owomugisha will also be joining us live from the IAS 2023 conference where she is serving as a rapporteur, to discuss the Statement’s relevance today.

HIV Justice Live! Episode 5: Bringing Science to Justice will be live on Facebook and YouTube on Tuesday 25th July at 3pm CEST (click here for your local time).

WHO publishes new policy guidelines describing the role of HIV viral suppression on stopping HIV transmission

The World Health Organization (WHO) is releasing new scientific and normative guidance on HIV at the 12thInternational IAS (the International AIDS Society) Conference on HIV Science.

New WHO guidance and an accompanying Lancet systematic review released today describe the role of HIV viral suppression and undetectable levels of virus in both improving individual health and halting onward HIV transmission. The guidance describes key HIV viral load thresholds and the approaches to measure levels of virus against these thresholds; for example, people living with HIV who achieve an undetectable level of virus by consistent use of antiretroviral therapy, do not transmit HIV to their sexual partner(s) and are at low risk of transmitting HIV vertically to their children. The evidence also indicates that there is negligible, or almost zero, risk of transmitting HIV when a person has a HIV viral load measurement of less than or equal to 1000 copies per mL, also commonly referred to as having a suppressed viral load.

Antiretroviral therapy continues to transform the lives of people living with HIV. People living with HIV who are diagnosed and treated early, and take their medication as prescribed, can expect to have the same health and life expectancy as their HIV-negative counterparts.

“For more than 20 years, countries all over the world have relied on WHO’s evidence-based guidelines to prevent, test for and treat HIV infection,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “The new guidelines we are publishing today will help countries to use powerful tools have the potential to transform the lives of millions of people living with or at risk of HIV.”

At the end of 2022, 29.8 million of the 39 million people living with HIV were taking antiretroviral treatment (which means 76% of all people living with HIV) with almost three-quarters of them (71%) living with suppressed HIV. This means that for those virally suppressed their health is well protected and they are not at risk of transmitting HIV to other people. While this is a very positive progress for adults living with HIV, viral load suppression in children living with HIV is only 46% – a reality that needs urgent attention.

Coming soon:

HIV Justice Live! Episode 5: Bringing Science to Justice

Five years ago, twenty of the world’s leading HIV scientists published the ‘Expert Consensus Statement on the Science of HIV in the Context of Criminal Law’ to address the misuse of HIV science in punitive laws and prosecutions against people living with HIV for acts related to sexual activity, biting, or spitting.

More than 70 scientists from 46 countries endorsed the Expert Consensus Statement prior to its publication in the Journal of the International AIDS Society (JIAS). The Statement was launched on 25th July 2018 at AIDS 2018, with the press conference generating global media coverage.

Building upon our initial 2020 scoping report, we recently undertook further extensive research to examine the impact of the Expert Consensus Statement in the five years since its publication.

On 25th July 2023 – exactly five years to the day of the original launch – we will not only be presenting our findings at the 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2023), we will also be launching the five-year impact report during our live webshow, HIV Justice Live!

Hosted by HJN’s Executive Director, Edwin J Bernard, the show will include a discussion with the report’s lead author, HJN’s Senior Policy Analyst Alison Symington, as well as interviews with Malawian judge Zione Ntaba, Taiwan activist Fletcher Chui, and SALC lawyer Tambudzai Gonese-Manjonjo on the Statement’s impact.

We’ll also hear from some of the Expert Consensus Statement’s authors, including Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, Salim S Abdool Karim, Linda-Gail Bekker, Chris Beyrer, Adeeba Kamarulzaman, Benjamin Young, and Peter Godfrey-Faussett.

Ugandan lawyer and HJN Supervisory Board member Immaculate Owomugisha will also be joining us live from the IAS 2023 conference in Brisbane, Australia where she is serving as a rapporteur, to discuss the Statement’s legacy and relevance today.

There will be opportunities to let us know the impact the Expert Consensus Statement has had in your advocacy and to ask questions live, so please save the date and time.

HIV Justice Live! Episode 5: Bringing Science to Justice will be live on our Facebook and YouTube pages on Tuesday 25th July at 3pm CEST (click here for your local time).

HJN’s Executive Director remarks

to the UNAIDS Board (PCB)

These remarks were made during the thematic session on reducing health inequities through tailored and systemic responses in priority and key populations especially transgender people, and the path to 2025 targets.

The HIV Justice Network is a community-based NGO leading a co-ordinated global response to HIV criminalisation. We’ve have heard so far about many different structural inequalities but not so much about HIV criminalisation, also covered in the background note, which disproportionately affects key populations, including transgender people, who are already criminalised or otherwise targeted by discriminatory legal systems and policies.

In fact, over 90 countries have criminal laws – based on stigma, not science – that single out people living with HIV based on our HIV-positive status. Another 40 or so countries have applied general criminal laws to unjustly prosecute and imprison people with HIV for acts that cause no risk, no harm or for which there is scant proof of either.

HIV criminalisation selectively scapegoats people living with HIV for a collective failure in HIV prevention policy including the responsibility of governments to create supportive and enabling legal environments for HIV prevention in the first place.

I last attended the PCB 12 years ago as a journalist highlighting the injustices of HIV criminalisation, which at the time was mostly overlooked as a significant legal barrier to the HIV response.

I return to the PCB as the HIV Justice Network’s Executive Director, financially supported by the Robert Carr Fund for civil society networks. Thank you to the governments that support the Fund, and for recognising that community-led global and regional networks of PLHIV and KPs are necessary and irreplaceable partners.

In the intervening years some progress has been made but far too many unjust laws continue to impact far too many people living with HIV, including trans people, gay men and other men who have sex with men, people who use drugs, sex workers and women and girls.

Today, I call on all member states that still have punitive and harmful laws that single out people living with HIV (and that’s almost all of you) to fulfil the commitments most of you made in the 2021 Political Declaration.

It would make our work so much easier if you returned from Geneva to persuade your own governments to do the right thing: either fully fund the Unified Budget, Results and Accountability Framework (UBRAF) or – the cheaper option – get rid of your own ineffective, counterproductive, punitive, discriminatory laws once and for all so we can finally achieve HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE!

New HIV Justice Academy content: Lessons from the Central African Republic’s HIV law reform success

In the mid-2000s, many countries across Africa adopted HIV laws. Many of these laws contained important protections covering discrimination, privacy, and access to medications. Unfortunately, they also included overly broad and ill-informed HIV criminalisation provisions.

The Central Africa Republic (CAR) adopted an HIV law in 2006 which not only criminalised HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission, it also required people living with HIV to undergo treatment as prescribed by a doctor and engage in protected sex and an obligation to disclose their HIV-positive status to sexual partners.

Given the significant problems with these aspects of the law, multiple law reform attempts were made but none were successful until a new law – Law 22-016 on HIV and AIDS in the Central African Republic – was finally enacted on 18 November 2022.

How did it happen? What changed? Why was the law finally reformed?

Christian Tshimbalanga is a lawyer from the Democratic Republic of Congo with many years’ experience working on human rights and HIV in Africa. Through his work with UNAIDS, Christian provided critical support to the law reform process following it through until Parliament voted on the law. Cécile Kazatchkine (Senior Policy Analyst at the HIV Legal Network) asked Christian to share lessons learned to help others working to reform problematic HIV laws.

Their 25 minute, French-language audio conversation is now available as an additional case study in Chapter 5 of the HIV Justice Academy’s free HIV Criminalisation Online Course: How to advocate against HIV criminalisation. A translated transcript of the conversation is also available in the English, Spanish and Russian version of the course.

Christian’s role was to accompany the process until the law was voted on in Parliament. Several elements of Christian’s account stood out for us:

- In his role as an UNAIDS representative and technical partner, Christian was able to devote significant time to the law reform process, monitoring what was happening and pushing the bill through each stage of the process. Having a dedicated person on the ground to accompany the legislative process on a day-to-day basis was critical to the success.

- Civil society was a key partner. The Central African Network of People Living with HIV (RECAPEV) and the Central African Network on Ethics and Rights (RCED) pushed hard for the law to be revised. UNAIDS provided them with a small amount of financial support which enabled them to increase their capacity to sustain this advocacy.

- Local partners and international organisations were also partners in the law reform efforts, including the National AIDS Council (CNLS), the Ministry of Health and the Minister of Justice, as well as UNDP, UNAIDS, and the French Red Cross (the principal recipient of Global Fund funding in CAR).

- A memorandum outlining the new bill was drafted by various stakeholders including civil society. It informed parliamentarians about the relevant public health and human rights issues and the scientific evidence related to HIV.

- Following the example of a previous forum in Madagascar on a draft law on sexual and reproductive health, a forum was organised for (primarily male) parliamentarians and their (female) spouses. Because issues of this intimate nature are often discussed in the home, involving spouses was strategic. Several people living with HIV opened the forum by talking about their lived realities and the persistence of HIV-related stigma and discrimination in CAR.

While worthy of celebration, the new legislation is not a complete victory. It does not fully decriminalise HIV but it does provide a much narrower definition of the prohibited conduct. Under the 2006 law, a person living with HIV could be prosecuted simply for HIV ‘exposure’ without neither intent nor transmission. The 2022 Act criminalises “intentional transmission of the virus,” defined as, inter alia, the fact that a person who knows his or her status intentionally transmits the virus through unprotected sexual relations without disclosing his or her seropositivity. A list of circumstances where the criminal law should not be applied is also included (e.g., in the case of transmission of the virus from a mother to her child).

For more information on the 2022 Act, see the HIV Justice Network’s Global HIV Criminalisation Database.

To enrol in the HIV Criminalisation Online Course, visit the HIV Justice Academy and sign up. It’s free!

Kenya: People living with HIV will continue to lobby for change after disappointing High Court decision

31 March 2023 – Nairobi, Kenya

Communities of people living with and affected by HIV are disappointed with the Nairobi High Court’s decision dismissing Petition 447 of 2018.

This is a Petition was filed in December 2018, that asked that the Court declare section 26 of the Sexual Offences Act 3 of 2006 to be unconstitutional, void and invalid, and therefore struck from the law. This law criminalises deliberate transmission and or exposure of life-threatening sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. The manner in which it has been interpreted has caused harm to persons living with HIV.

On 20 December 2022, Justice Ong’udi in the Nairobi High Court dismissed the

Petition, upholding the law’s constitutionality.

“We are disappointed with the judgment. Evidence from across the world shows us that criminalisation does not prevent HIV transmission. It makes effective HIV testing, treatment and disclosure harder and it increases stigma and discrimination”, said Carlin Kizito.

The communities were particularly concerned that the law leaves women living with HIV vulnerable to unjust prosecution. “Women are usually the first to find out about their

HIV status when they test during pregnancy. Because of this, the law makes them vulnerable to prosecution because they will be assumed to be the one who brought HIV into the relationship even when this is not the case,” said Jerop Limo, Executive Director of Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health Program (AYARHEP)

Maurine Murenga of Lean on Me Foundation said that the State does not have the means to prove scientifically that one person necessarily transmitted HIV to another.

She said further, “Laws like this also spread misinformation about HIV. We’ve seen a number of women living with HIV being prosecuted for breastfeeding, yet breastfeeding guidelines state that breastfeeding is safe for women on HIV treatment. In fact, the World Health Organisation recommends it.” Maurine further added that “HIV is not a crime or a death sentence. With effective treatment, you can live a long and healthy life. Effective treatment also makes HIV undetectable and therefore untransmissible. Testing, treatment and support should be our focus, not punishment,”

Bozzi Ongala of the Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health Program (AYARHEP) spoke on the need for using science to improve laws on HIV, “We urge that there be a progressive updates in the law in response to Scientific advancements on HIV research.”

“We, the networks of people living with HIV are encouraged that the Petitioners intend to appeal the judgment. We shall continue to lobby the government to change the law. On behalf of people living with HIV, we look forward to positive justice.” said Patricia Asero of ICW Kenya.

Signed:

- Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health Program (AYARHEP)

- ICW Kenya

- DACASA

- Operation Hope Community Based Organization

- Network of People Living with HIV (NEPHAK)

- Lean on Me

- MOYOTE

- YPLUS Kenya

Transgender Day of Visibility 2023

Honouring the courage of transgender people globally, especially transgender people living with HIV

Today is International Transgender Day of Visibility, held annually on 31st March to celebrate transgender people globally and honour their courage and visibility to live openly and authentically.

This year’s 14th annual celebration is a day to also raise awareness around the stigma, discrimination and criminalisation that transgender people face.

According to the Human Dignity Trust, 14 countries currently criminalise the gender identity and/or expression of transgender people, using so-called ‘cross-dressing’, ‘impersonation’ and ‘disguise’ laws. In many more countries transgender people are targeted by a range of laws that criminalise same-sex activity and vagrancy, hooliganism and public order offences.

Transgender people living with HIV can be further criminalised based on their HIV-positive status, although we know that there are still too many invisibilities around the impact of HIV criminalisation on transgender people.

Cecilia Chung, Senior Director of Strategic Initiatives and Evaluation of the Transgender Law Center, who is also a member of our Global Advisory Panel told our 2020 Beyond Blame webinar that there are not enough data on the impact of HIV criminalisation laws on transgender people. She said such data are not “uniformly collected across the world… The numbers still remain invisible even though we know for sure there are [HIV criminalisation] cases.”

HJN honours the courage of transgender people – especially transgender people living with HIV – to live openly and authentically. We also call for more visibility for transgender people in data collection, as well as reforms of all criminal laws and their enforcement that disproportionately target transgender people.

An important new advocacy tool for HIV justice

New international principles provide guidance on many aspects of overcriminalisation, including HIV criminalisation

This week saw the long-awaited publication of the 8 March Principles for a Human Rights-Based Approach to Criminal Law Proscribing Conduct Associated with Sex, Reproduction, Drug Use, HIV, Homelessness and Poverty by the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ).

The 21 principles aim to address the detrimental impact of overcriminalisation of a wide range of conduct – including HIV criminalisation – on health, equality, and other human rights, and seek to offer guidance on the application of criminal law in a way that upholds human rights.

The principles offer a clear, accessible, and operational legal framework and practical legal guidance on the application of criminal law to:

- sexual and reproductive health and rights, including abortion;

- consensual sexual activities, including in such contexts as sex outside marriage, same-sex sexual relations, adolescent sexual activity, and sex work;

- gender identity and gender expression;

- HIV non-disclosure, exposure, or transmission;

- drug use and the possession of drugs for personal use;

- and homelessness and poverty.

The principles were launched on Wednesday, March 8 – International Women’s Day – at a side-event at the 52nd Session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director, Christine Stegling, welcomed the fact that these principles were named after, and were being launched on, International Women’s Day, “in recognition of the detrimental effects criminal law can, and too often does have on women in all their diversity.”

Volker Türk, High Commissioner for Human Rights, also noted the significance of the name and the launch on International Women’s Day: “Today is an opportunity for all of us to think about power and male dominated systems,” he said.

What do the principles cover?

The first six principles cover legality, harm, individual criminal liability, voluntary act requirement, mental state requirement, and grounds for excluding criminal liability.

The next seven principles cover the following areas: criminal law and international human rights law and standards; human rights restrictions on criminal law; legitimate exercise of human rights; criminal law and prohibited discrimination; criminal liability may not be based on discriminatory grounds; limitations on criminal liability for persons under 18 years of age; criminal law and non-derogable human rights; and criminal law sanctions.

The final eight principles cover specific areas: sexual and reproductive health and rights; abortion; consensual sexual conduct; sex work; sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression; HIV non-disclosure, exposure, or transmission; drug use and possession, purchase, or cultivation of drugs for personal use; life-sustaining activities in public places and conduct associated with homelessness and poverty.

How were the principles developed?

The idea for the principles came out of a 2018 meeting convened by the ICJ with UNAIDS and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). This convening endorsed the call by civil society and other stakeholders for the elaboration of a set of jurists’ principles to assist legislatures, the courts, administrative and prosecutorial authorities, and advocates to address the detrimental human rights impact of criminalisation in the above-mentioned areas.

Following this initial expert meeting, the ICJ engaged in a lengthy consultative process. For example, the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE coalition submitted this response in 2019. Ultimately, a wide range of expert jurists, academics, legal practitioners, human rights defenders, and civil society organisations across the world reviewed and eventually endorsed or supported the principles.

Jurists who have endorsed the principles so far include: HJN Global Advisory Panel (GAP) member, Zione Ntaba, Justice of the High Court Malawi; former HJN GAP member Edwin Cameron, Retired Justice, Constitutional Court of South Africa and Inspecting Judge, Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services; and the Chair of HJN’s Supervisory Board, Richard Elliott.

The HIV Justice Network was one of several organisations and institutions to be the first to support the principles alongside Amnesty International, CREA, the Global Network of Sex Work Projects, and the International Network of People who Use Drugs.

You can find the principles on the ICJ website as well as in the English language version of the HIV Justice Academy’s Resource Library.

New principles lay out human rights-based approach to criminal law

The International Committee of Jurists (ICJ) along with UNAIDS and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) officially launched a new set of expert jurist legal principles to guide the application of international human rights law to criminal law.

The ‘8 March principles’ as they are called lay out a human rights-based approach to laws criminalising conduct in relation to sex, drug use, HIV, sexual and reproductive health, homelessness and poverty.

Ian Seiderman, Law and Policy Director at ICJ said, “Criminal law is among the harshest of tools at the disposal of the State to exert control over individuals…as such, it ought to be a measure of last resort however, globally, there has been a growing trend towards overcriminalization.”

“We must acknowledge that these laws not only violate human rights, but the fundamental principles of criminal law themselves,” he said.

For Edwin Cameron, former South Africa Justice of the Constitutional Court and current Inspecting Judge for the South African Correctional Services, the principles are of immediate pertinence and use for judges, legislators, policymakers, civil society and academics. “The 8 March principles provide a clear, accessible and practical legal framework based on international criminal law and international human rights law,” he said.

The principles are the outcome of a 2018 workshop organized by UNAIDS and OHCHR along with the ICJ to discuss the role of jurists in addressing the harmful human rights impact of criminal laws. The meeting resulted in a call for a set of jurists’ principles to assist the courts, legislatures, advocates and prosecutors to address the detrimental human rights impact of such laws.

The principles, developed over five years, are based on feedback and reviews from a range of experts and stakeholders. They were finalized in 2022. Initially, the principles focused on the impact of criminal laws proscribing sexual and reproductive health and rights, consensual sexual activity, gender identity, gender expression, HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission, drug use and the possession of drugs for personal use. Later, based on the inputs of civil society and other stakeholders, criminalization linked to homelessness and poverty were also included.

Continued overuse of criminal law by governments and in some cases arbitrary and discriminatory criminal laws have led to a number of human rights violations. They also perpetuate stigma, harmful gender stereotypes and discrimination based on such grounds as gender or sexual orientation.

In 2023, twenty countries criminalize or otherwise prosecute transgender people, 67 countries still criminalize same-sex sexual activity, 115 report criminalizing drug use, more than 130 criminalize HIV exposure, non-disclosure and transmission and over 150 countries criminalize some aspect of sex work.

In the world of HIV, the abuse and misuse of criminal laws not only affects the right to health, but a multitude of rights including: to be free from discrimination, to housing, security of the person, movement, family, privacy and bodily autonomy, and in extreme cases the very right to life. In countries where sex work is criminalized, for example, sex workers are seven times more likely to be living with HIV than where it is partially legalized. To be criminalized can also mean being deprived of the protection of the law and law enforcement. And yet, criminalized communities, particularly women, are often more likely to need the very protection they are denied.

UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director for the Policy, Advocacy and Knowledge Branch, Christine Stegling said, “I welcome the fact that these principles are being launched on International Women’s Day (IWD), in recognition of the detrimental effects criminal law can, and too often does have on women in all their diversity.”

“We will not end AIDS as a public health threat as long as these pernicious laws remain,” she added. “These principles will be of great use to us and our partners in our endeavors.”

Also remarking on the significance of IWD, Volker Türk, High Commissioner for Human Rights, said, “Today is an opportunity for all of us to think about power and male dominated systems.”

His remarks ended with, “I am glad that you have done this work, we need to use it and we need to use it also in a much more political context when it comes precisely to counter these power dynamics.”

“Frankly we need to ask these questions and make sure that they are part and parcel going forward as to what human rights means,” he said.

In conclusion, Phelister Abdalla, President of the Global Network of Sex Work Projects, based in Kenya noted: “When sex work is criminalized it sends the message that sex workers can be abused…We are human beings and sex workers are entitled to all human rights.”