The second HIV is Not a Crime meeting, now a Training Academy, will take place between May 17 – 20, 2016 at the University of Alabama in Huntsville.

The Training Academy will unite and train advocates living with HIV and allies from North America on laws, policies and practices criminalising people living with and vulnerable to HIV and on strategies and best practices for improving legal environments.

There will be three tracks, focused on

1) Effective and Accountable Leadership,

2) Rights, Policy and Justice, and

3) Campaign Planning, Strategy and Messaging.

Workshops will help advance informed and effective grassroots organising and coalition-building, providing participants with concrete tools and resources to work on state-level strategies when they return home.

Advocates working on HIV criminalisation in the United States, Canada or Mexico are encouraged to submit an application to conduct a workshop at the Training Academy and contribute to this growing and important movement.

Deadline for submissions is Friday, February 26, 2016 by 5:00 pm CST (6:00 pm EST, 3:00 PST).

Descriptions of workshop tracks are below:

Effective and Accountable Leadership

This track will focus on building relevant and current leadership skills for an effective and intersectional criminalisation movement.

Sessions considered may include coalition-building, development of individual leadership skills or emphasise disproportionately impacted communities.

Rights, Policy, and Justice

This track will focus on policy issues, criminal justice, and advocacy strategies relevant to disproportionately criminalized communities.

Submissions on issues specific to communities targeted by policing practices due to race, gender identity, sexual orientation, substance use, immigration status, and other forms of discrimination are encouraged.

Campaign Planning, Strategy and Messaging

This track will provide resources, tools and skills advocates need to successfully develop and implement a state-level campaign to repeal or modernize criminalization laws.

Submissions may focus on the “nuts-and-bolts” required for organizing, including messaging research and positioning, how to best utilize research to persuade media, policy leaders and legislators and creation and execution of a campaign plan.

After reviewing proposals, conference organizers may invite session organizers to collaborate on a session. All presenters are required to register for the conference. Acceptance of a proposal does not guarantee a scholarship or coverage of any of the necessary registration or travel expenses.

We expect to receive more breakout session proposals than we can actually accommodate. When making selection decisions, we have many considerations to balance, including our desire to elevate diverse leadership and new organizations and voices into the mix at each Training Academy. Please read the criteria below for what we are and are not looking for.

Proposals that meet all or most of these criteria will be given the most favorable consideration:

- Participatory: Proposed session is interactive, with lots of two-way communication between participants and presenters and hands-on engaging activities.

- Timely: Proposal demonstrates an understanding of current criminal justice, policing, and criminalization environment

- Intersectional: Proposal demonstrates an intersectional analysis

- Practical: Session proposes to leave participants with useful tools, including innovative strategies, exemplary models, powerful narratives, and accessible artistic and cultural expressions.

- Action-Oriented: Session connects to active issue campaigns, grassroots community organizing, and current struggles and/or movement building efforts.

- Intergenerational: The content is relevant to, and encouraging of, the participation of youth and young people, as well as multi-generational strategies.

- Geographic Diversity: For national audience, we want the content and facilitators to relate to different geographic areas, especially the South.

- Multiracial: Sessions include a multiracial and intersectional analysis and approach — even if there is a mono-racial emphasis. A multiracial team of facilitators is also encouraged.

Breakout Sessions should not consist of:

- Lectures, presentations of academic papers or mostly theory, or panels that primarily involve people talking at others.

- Sessions that do not have a connection to people working in local communities.

- Sessions that focus primarily on a problem, without equal or greater attention to proposed solutions.

- Sessions by individuals not engaged with, connected or accountable to social justice organizations or communities.

Important Notes:

The deadline for submission is Friday, February 26, 2016 by 5:00 pm CST (6:00 pm EST, 3:00 PST). You will receive notice of acceptance on Friday, April 1, 2016.

Applicants may submit up to two workshops for consideration. For each 90-minute workshop, applicants should follow the suggested format below. Workshops submissions must be one page in length and be in a font 11 point or over but not smaller. Your submission will not be reviewed if it is more than one page (8.5 x 11) in length or if the font is smaller than 11 point. There is no limit to the number of total presenters on a workshop.

Workshop submissions will be reviewed and evaluated by a volunteer Program Work Group on the following criteria: 1) alignment with track description, SERO and PWN-USA values, and Training Academy goals 2) clarity of description 3) appropriateness of suggested format.

We strongly encourage applicants to consider formats that engage participants, rather than simply presenting information. In addition, the program committee will review overall workshop acceptances with an eye towards diversity of presenters, particularly in demographics, geography, skills, and expertise.

Every proposal must include:

- FIRST, LAST NAME OF LEAD PRESENTER(S):

- FIRST, LAST NAME(S) OF ADDITIONAL PRESENTER(S):

- EMAIL ADDRESS/PHONE NUMBER FOR LEAD PRESENTER:

- TITLE & ORGANIZATIONAL AFFILIATION FOR ALL PRESENTERS:

- WORKSHOP TRACK: 1) Effective and Accountable Leadership 2) Rights, Policy & Justice; 3) Campaign Planning, Strategy and Messaging

- PROPOSED WORKSHOP TITLE:

- WORKSHOP DESCRIPTION:

- WORKSHOP OBJECTIVE(S):

- FORMAT OF WORKSHOP: Describe how you and/or presenter(s) will conduct the workshop, i.e. presentation style, opportunity for discussion and/or interactive activities/exercises.

Email workshop submissions by Friday, February 26, 2016 to: conference@seroproject.com

All other questions regarding the Summit should be emailed to Tami Haught at: tami.haught@seroproject.com

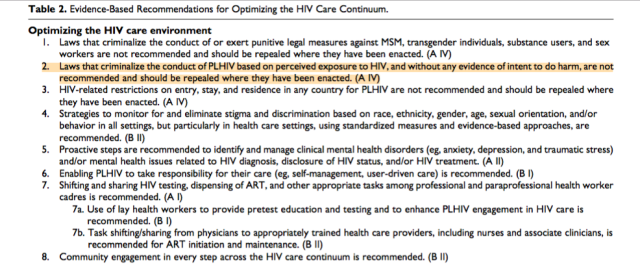

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.