A video recorded by presidential candidate Hillary Clinton specifically for the HIV is Not a Crime II – Training Academy.

HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE partners, SERO Project and PWN-USA, bring together advocates from U.S. & 4 countries to 2nd National HIV Is Not a Crime Training Academy at University of Alabama-Huntsville

Advocates from 34 states & 4 other countries convene at University of Alabama-Huntsville to strategize Addressing Discriminatory HIV Laws at 2nd National HIV Is Not a Crime Training Academy.

Even as a bill repealing Colorado’s HIV criminalization laws awaits the governor’s pen, much work remains to be done to bring laws up to date with current science in at least 33 states.

Eleven states have laws on the books that can send people living with HIV to prison for behaviors (such as biting and spitting) that carry virtually no risk of transmitting HIV. Forty-four states have prosecuted people living with HIV for perceived exposure or transmission; most states permit prosecution even when no transmission has occurred, and actual risk is negligible.

In Texas, a man living with HIV is currently serving a 35-year sentence for spitting. In Idaho, Kerry Thomas is serving 30 years for allegedly not disclosing his HIV status to a partner – despite the fact that he took measures to prevent transmission, including using a condom and taking medications to maintain an undetectable viral load. Kerry Thomas’ accuser never acquired HIV. Yet his appeal was recently denied, demonstrating that current science continues not to matter to the courts.

“These laws make disclosure harder. Because we so fear the punishment, we just keep things bottled up inside,” says Monique Howell-Moree, who was prosecuted under a US military non-disclosure law and would have faced 8-12 years if convicted. “I didn’t know the best way to disclose … Had I had the support and knowledge that I have now back then, I would most definitely have done things differently.”

In her HIV/AIDS platform and in a recent meeting with activists, U.S. presidential candidate Hillary Clinton called for “reform[ing] outdated and stigmatizing HIV criminalization laws.” Sen. Bernie Sanders’ campaign has said the candidate is also “absolutely opposed” to these laws, according to the Washington Blade. The confluence of outdated laws, unjust prosecutions and profound disparities is bringing advocates and activists from 34 states and 4 countries together for the second national convening dedicated exclusively to strategizing to fight back in the name of human rights and public health.

WHAT: HIV Is Not a Crime II National Training Academy

WHERE: University of Alabama, Huntsville

WHEN: May 17-20, 2016

The Training Academy is co-organized by SERO Project and Positive Women’s Network-USA, two national networks of people living with HIV. It comes on the heels of a major victory in Colorado, where through the dedicated efforts of a group known as the “CO Mod Squad” (“mod” refers to “modernization” of the law), led by Positive Women’s Network-USA (PWN-USA) Colorado, a bill was passed last week that updates laws to take account of current science and eliminates HIV criminalization language.

“With people living with HIV leading the way and our allies supporting us, we were able to do something many thought we couldn’t,” said Barb Cardell, co-chair of PWN-USA Colorado and one of the leaders of the successful efforts. “The law now focuses on proven methods of protecting public health — like education and counseling — while discarding the language of criminalization, which actually discourages testing, treatment and disclosure.”

“This law represents real progress for Coloradans, regardless of their HIV status,” she added. At the Training Academy this week, Cardell will share some highlights and lessons learned from the CO Mod Squad’s experience.

Keynote speakers at the Training Academy include Mary Fisher, who stunned the audience at the 1992 Republican National Convention with a speech about her experience as a woman living with HIV; Joel Goldman, longtime advocate and managing director of the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation; and Colorado state senator Pat Steadman, the senate sponsor of the bill just passed repealing HIV criminalization in his state. Session topics will explore best practices for changing policy, and will consider the intersections of HIV criminalization with issues ranging from institutional racism to transphobia, criminalization of sex work, mental illness and substance use, and overpolicing of marginalized communities.

“The goals of the Training Academy go beyond giving advocates the tools and know-how they need to change policy, to deepening our collective understanding of the impact of these laws and why they are enforced the way they are,” said Naina Khanna, executive director of PWN-USA. “We hope participants will leave better prepared to effect change by thinking differently, forging new partnerships and ensuring communities most heavily impacted by criminalization are in leadership in this movement.”

At SADC-PF parliamentarians meeting in South Africa, Patrick Eba of UNAIDS says HIV criminalization is a setback to regional AIDS efforts

The criminalisation of HIV simply undermines the remarkable global scientific advances and proven public health strategies that could open the path to vanquishing AIDS by 2030, Patrick Eba from the human rights and law division of UNAIDS told SADC-PF parliamentarians meeting in South Africa.

Restating a remark made by Justice Edwin Cameron of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, Eba said: “HIV criminalisation makes it more difficult for those at risk of HIV to access testing and prevention. There is simply no evidence that it works. It undermines the remarkable scientific advances and proven public health strategies that open the path to vanquishing AIDS by 2030.”

SADC-PF has undertaken, as part of its commitment to advocacy for sexual reproductive health rights, an ambitious 90-90-90 initiative in east and southern Africa, with the help of the media, to ensure that all people living with HIV should know their status by 2020; that by 2020 90 percent of all people diagonised with HIV will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy; and that by 2020 90 percent of all people living with HIV and receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression.

He implored parliamentarians from SADC-PF member states to advocate for laws that would decriminalise HIV after he noted several African countries had HIV-specific criminal laws that resulted in arrests and prosecutions of those convicted of spreading HIV intentionally.

Eba said calls for the criminalisation of intentional or wilful spreading of HIV stem from the fact there are high rates of rape and sexual violence, and most notably in post-conflict countries such as the DRC there exist promises of retribution, incapacitation, deterrence and rehabilitation.

He gave an example of one case of miscarriage of justice involving a woman in Gabon who was wrongfully arrested after a man accused her of having infected him with HIV, but after spending several months in detention she was actually found to be HIV-negative after she went for testing.

Eba appealed to SADC-PF parliamentarians to consider decriminalisation of HIV on the basis that antiretroviral treatment (ART) has a 96 percent rate in reducing the risk of HIV transmission.

“End criminalisation to end AIDS,” he implored SADC-PF parliamentarians who included Agnes Limbo of the RDP, Ida Hoffmann of Swapo and Ignatius Shixwameni of APP, all delegated by Namibia to the conference.

Eba also referred to the motion unanimously adopted in November 2015 that was moved by Duma Boko of Botswana and that was seconded by Ahmed Shaik Imam of South Africa who reaffirmed SADC member states’ obligation to respect, fulfil and promote human rights in all endevours undertaken for the prevention and treatment of HIV.

That motion had also called on SADC member states to consider rescinding and reviewing punitive laws specific to the prosecution of HIV transmission, exposure and non-disclosure. It also reiterated the role by parliamentarians to enact laws that support evidence-based HIV prevention and treatment interventions that conform with regional and international human rights frameworks.

Eba said since HIV infection is now a chronic treatable health condition, no charges of “murder” or “manslaughter” should arise and that HIV non-disclosure and exposure should not be criminalised in the absence of transmission, and that significant risk of transmission should be based on best available scientific and medical evidence.

On the other hand, he said, there is no significant risk in cases of consistent condom use practice or other forms of safer sex and effective HIV treatment.

The SADC-PF joint sessions also addressed the issues of criminalisation of termination of pregnancy. The joint sessions ended on Thursday with a raft of recommendations for the ministerial meetings.

Originally published in New Era.

US: Blog post by HIV criminalisation survivor Monique Howell-Moree

My name is Monique Howell-Moree. As a survivor of HIV criminalization myself, I believe laws criminalizing HIV definitely need to be changed. I would have had to serve 8 to 12 years if I had been convicted, because my state, like most states, does not take into consideration current science of the risk transmission. Nobody wants to take the time to educate themselves and update themselves on what we now know about transmission risks– especially when someone is in care and taking care of themselves–and the result is unjust laws and prosecutions. Transmission rates when in care are so low compared to how things were in the ’80s and early ’90s, yet laws have not kept up with medical advances.

A lot of these laws are very outdated, and stigma is what is still keeping these laws alive. I believe that most states still live in fear of the unknown. They still have stigma circulating around their communities, and they refuse to bring about CHANGE. Ignorance and lack of knowledge are still prevalent in many states.

When I was on trial myself, not one person in the room knew much about HIV. If I was convicted I could have possibly lost my children, home, and would even have been labeled a sex offender. That’s not even fair, when so many other crimes are so much worse than this. HIV is not a death sentence, but people in many states still believe it is. If someone is intentionally trying to put their partner at risk, then yes, we do need to make sure there is a remedy, because of course we are trying to stop the spread of HIV. But if someone just is afraid, not educated and doesn’t have the support they need when disclosing their status, that’s when our local ASOs and HIV organizations need to come together and show them how to say the right words and do the right thing when disclosing. Women are sometimes even in a violent relationship and fear the repercussions of disclosure, or are afraid to say the words that they need to say due to embarrassment or guilt.

These outdated laws also cause people to actually be afraid, because the laws are worded as if we are the worst people on this earth. People fear of losing their jobs, homes, children etc. These laws makes no sense, and the punishment definitely doesn’t fit the “crime.”

Many factors can play into why a individual discloses or does not disclose. If we can raise more awareness about HIV everywhere, even in the workforce, then maybe, just maybe, people’s views will evolve. Sharing our testimonials and allowing policymakers and the public to hear our hearts will also help. We must take responsibility for ourselves and also stand for what we believe is fair and right.

When I was charged, I had none of this type of support. Serving my country at the time in the Army, I only signed a form in tiny, tiny fine print saying to make sure I tell my status if I should engage in any sexual act, and that was it. Still afraid and fearing rejection, I didn’t know the best way to disclose, and didn’t even think I would get into another relationship after my diagnosis. Had I had the support and knowledge that I have now back then, I would have most definitely have done things differently. I wouldn’t have been ashamed of who I was, and I would have been honest and disclosed my status when involved in a sexual act.

Changing these laws will have a major impact on many HIV survivors. We shouldn’t have to live in fear of being who we are. Intentionally trying to cause harm is different from just needing support and help on how to disclose the proper way when necessary. We fear rejection, but the laws make disclosure even harder, because we so fear the punishment that we just keep things bottled up inside as a safe place. Disclosing can be tough. I’m a living witness to that; but we can help many if we continue to raise awareness on HIV criminalization. Many are behind bars for cases where no transmission had taken place, but HIV stigma makes the system want to lock us up, rather than educating policymakers and the public.

My sisters and brothers that are living with HIV: We must have each other’s backs and support one another, because the laws are definitely set up to pit us against a society that has not a clue that we are still human beings and deserve to be treated fairly and not as if we still live in the 1980s. So much has improved since then, and it’s time that we all take a stand to help get these laws changed!!!

More Advocacy Needed to Stop HIV Criminalisation

People living with HIV face increased criminalisation and prosecution based on their HIV status, finds a new report by the HIV Justice Network and the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+).

HIV criminalisation is the application of the criminal law to people living with HIV based solely on their HIV status. This happens through HIV-specific criminal statutes, or by applying general criminal laws that allow for prosecution of unintentional HIV transmission, potential or perceived exposure to HIV without transmission, and/or non-disclosure of known HIV-positive status.

The use of criminal laws against people with HIV impacts entire communities. It perpetuates stigma, discrimination and feelings of fear, shame and anger towards people living with HIV.

“These laws and prosecutions do not only impact the people investigated, prosecuted, or incarcerated. These laws undermine core sexual rights and public health principles. Their existence and application exacerbate racial and gender inequalities and jeopardize critical HIV prevention and service delivery efforts” says Julian Hows of GNP+.

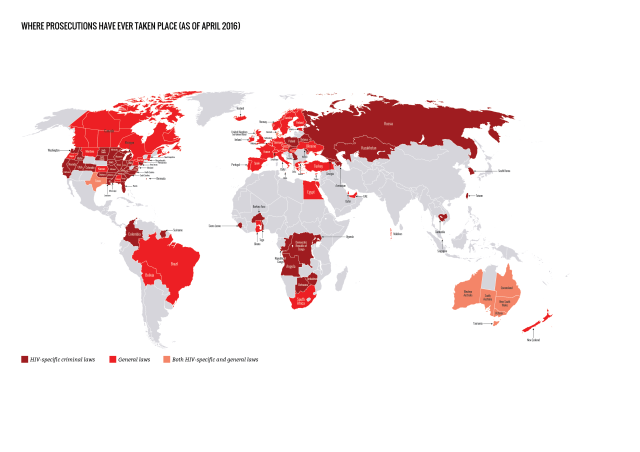

The report, Advancing HIV Justice 2: building momentum in global advocacy against HIV finds a total of 72 countries have adopted laws that specifically allow for HIV criminalisation. In these countries laws are either HIV-specific, or name HIV as one (or more) of the diseases covered by the law. Prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, potential or perceived exposure and/or unintentional transmission have now been reported in 61 countries.

Of particular concern is the fact that 30 sub-Saharan African countries have now enacted overly broad and/or vague HIV specific statues enabling legal repercussions against people living with HIV. The report shows the highest number of prosecutions are being reported in Russia, the United States, Belarus and Canada.

The trend is in contrast with the latest science which shows that people with HIV who adhere to HIV treatment and have an undetectable viral load are not infectious. In addition this approach of the criminal law violates key legal and human rights principles.

HIV criminalisation does not exist in vacuum. It is often linked to punitive laws and policies that impact sexual and reproductive health and rights, especially those aimed at sex workers, current and former drug users (particularly people living with hepatitis C), transgender people and/or men who have sex with men and other sexual minorities.

Click here to read the new report and visit the HIV Justice Network for more information on how you can get involved in the movement to eliminate HIV – or modernise – HIV criminalisation laws.

New report shows HIV criminalisation is a growing, global concern but advocates are fighting back

A new report released today shows that HIV criminalisation is a growing, global phenomenon. However, advocates around the world are working hard to ensure that the criminal law’s approach to people living with HIV fits with up-to-date science, as well as key legal and human rights principles.

Click on this link to read or download Advancing HIV Justice 2: Building momentum in global advocacy against HIV criminalisation.

What do we mean by ‘HIV criminalisation’?

HIV criminalisation describes the unjust application of the criminal law to people living with HIV based solely on their HIV status – either via HIV-specific criminal statutes, or by applying general criminal laws that allow for prosecution of unintentional HIV transmission, potential or perceived exposure to HIV where HIV was not transmitted, and/or non-disclosure of known HIV-positive status.

Such unjust application of the criminal law in relation to HIV is (i) not guided by the best available scientific and medical evidence relating to HIV, (ii) fails to uphold the principles of legal and judicial fairness (including key criminal law principles of legality, foreseeability, intent, causality, proportionality and proof), and (iii) infringes upon the human rights of those involved in criminal law cases.

What is the impact of HIV criminalisation?

Understanding the potential negative impact of HIV criminalisation on public health is critical to making informed policy decisions.

The last few years have seen increasing interest among researchers in the area of HIV criminalisation and a push into new areas of enquiry to examine the impacts of the unjust application of criminal law.

The report summarises a body of research which shows that instead of delivering a public health benefit, HIV criminalisation is a poor public health strategy, exacerbating racial and gender inequalities and negatively impacting a number of key areas including: testing; disclosure; sexual behaviour; and healthcare practice.

How many countries around the world have HIV criminalisation laws?

Since our last report, we found an increase in the number of countries that specifically allow for HIV criminalisation: these could be stand-alone HIV-specific criminal laws, part of omnibus HIV laws, or criminal and/or public health laws that specifically mention HIV.

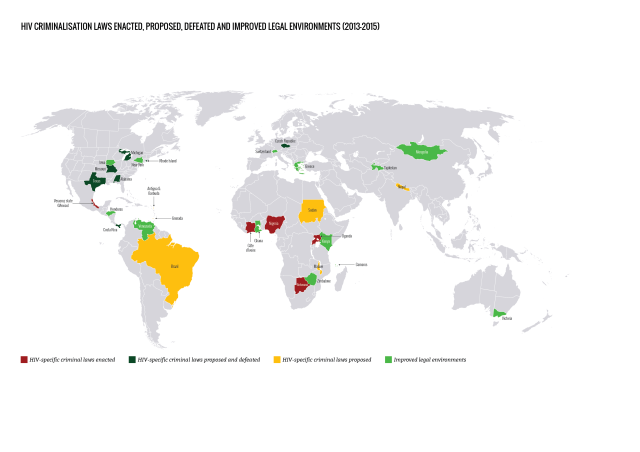

Some of this increase is due to laws enacted since 2013 in Botswana, Cote d’lvoire, Nigeria, Uganda and Veracruz state (Mexico), and some is due to improved reporting and research methodology.

Our analysis shows that a total of 72 countries have adopted laws that specifically allow for HIV criminalisation, either because the law is HIV-specific, or because it names HIV as one (or more) of the diseases covered by the law. This total increases to 101 jurisdictions when the HIV criminalisation laws in 30 of the states that make up the United States are counted individually.

How many countries have prosecuted people living with HIV?

Prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, potential or perceived exposure and/or unintentional transmission have now been reported in 61 countries. This total increases to 105 jurisdictions when individual US states and Australian states / territories are counted separately.

Of the 61 countries, 26 applied HIV criminalisation laws, 32 applied general criminal or public health laws, and three (Australia, Denmark and United States) applied both HIV criminalisation and general laws.

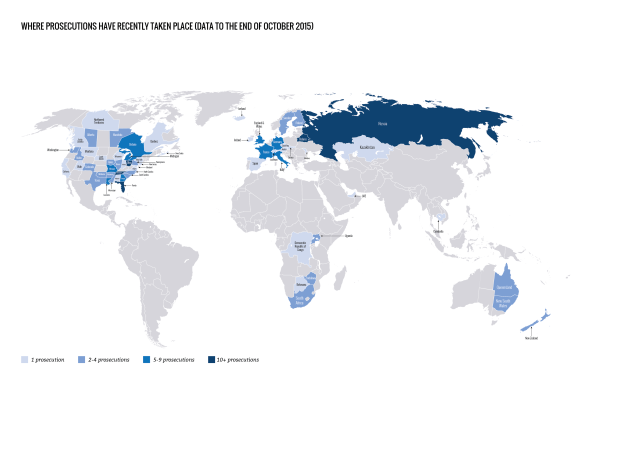

Where have prosecutions recently taken place?

We found reports of at least 313 arrests, prosecutions and/or convictions in 28 countries during the report period, covering 1 April 2013 to 30 September 2015.

Of note, we are now able to include data on reported prosecutions in Belarus and Russia, which are likely to have been taking place at least since the enactment of a Belarusian public health law in 1993 and a Russian HIV criminalisation law in 1995.

The highest number of cases during this period were reported in:

• Russia (at least 115) • United States (at least 104) • Belarus (at least 20) • Canada (at least 17) • France (at least 7) • United Kingdom (at least 6) • Italy (at least 6) • Australia (at least 5) • Germany (at least 5).

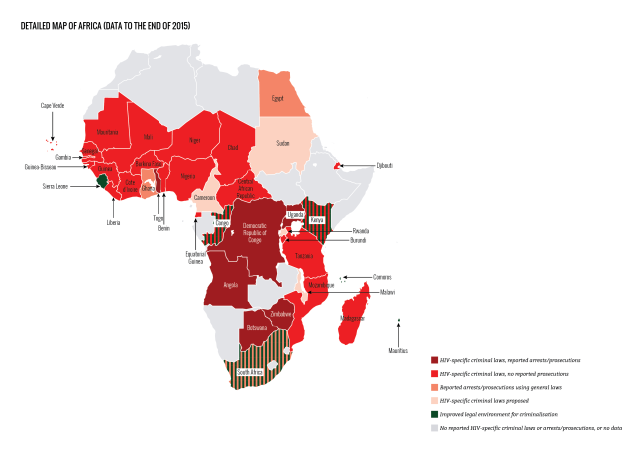

HIV criminalisation in sub-Sarahan Africa of increasing concern

Where there was no HIV criminalisation at the start of the 21st century, 30 sub-Saharan African countries have now enacted overly broad and/or vague HIV-specific criminal statutes.

Most of these statutes are part of omnibus HIV-specific laws that also include protective provisions, such as those relating to non-discrimination in employment, health and housing. However, they also include a number of problematic provisions such as compulsory HIV testing and involuntary partner notification, as well as HIV criminalisation.

During the period covered by this report four countries in sub-Saharan Africa passed new HIV criminalisation laws: Botswana, Cote d’lvoire, Nigeria and Uganda.

Very few countries in Africa are now unaffected by problematic HIV criminalisation laws. The rise of reported prosecutions in Africa during this period (in Botswana, South Africa, Uganda, and especially Zimbabwe), along with the continuing, growing number of HIV criminalisation laws on this continent, is especially alarming.

Where has advocacy improved legal environments?

Important and promising developments in case law, law reform and policy have taken place in many jurisdictions, most of which came about as a direct result of advocacy.

During the report period, although an additional 13 jurisdictions in nine countries proposed new HIV criminalisation laws, seven of these were not passed, primarily due to swift and effective advocacy against them at an early stage. Advocacy in another ten jurisdictions in seven countries challenged, improved or repealed HIV criminalisation laws.

The legal environment relating to HIV criminalisation has improved in a small number of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, most notably in Kenya. On 18 March 2015, Kenya’s High Court ruled that its HIV criminalisation provision – Section 24 of the HIV Prevention and Control Act 2006 – was unconstitutional because it was vague, overbroad and lacking in legal certainty, particularly in respect to the term ‘sexual contact’.

The Court also found it contravened Article 31 of the Kenyan Constitution which guarantees the right to privacy because the law created an obligation for people with HIV to disclose their status to their ‘sexual contacts’, with no corresponding obligation for recipients of such sensitive medical information to keep it confidential.

Using science as an advocacy tool

Increased knowledge about reduced infectiousness due to antiretroviral therapy has led to advocacy that resulted in a number of jurisdictions revising or revisiting their criminal laws or prosecutorial policies relating to HIV criminalisation, although progress has been frustratingly slow.

Following the ‘Swiss statement’, published in January 2008, a growing number of courts, government ministries and prosecutorial authorities have accepted antiretroviral therapy’s impact on reducing the risk of both HIV exposure and transmission.

However, scientific advances alone will neither ‘end AIDS’ nor end HIV criminalisation. Although the impact of antiretroviral therapy on infectiousness is an important advocacy tool, it must be remembered that many people with HIV do not have access to treatment (or are unable to achieve an undetectable viral load when on treatment) and that everyone has a right to choose not to know their status and/or start treatment and should not be stigmatised nor considered ‘second class citizens’ should they wish to delay diagnosis or antiretroviral therapy.

More work required

Despite the many incremental successes of the past few years, much more work is required to strengthen advocacy capacity. This is why a coalition of seven organisations launched HIV Justice Worldwide in April 2016.

We also need to be aware that HIV criminalisation does not exist in vacuum, and is often linked to punitive laws and policies that impact sexual and reproductive health and rights, especially those aimed at sex workers and/or men who have sex with men and other sexual minorities.

And, bearing in mind the stigma faced by those with, for example, hepatitis C and concerns over the sexual transmission of the Ebola and Zika viruses, as we move forward to eliminate – or modernise – HIV criminalisation laws, we must ensure that our work does not inadvertently lead to the further criminalisation of other communicable and/or sexually transmitted infections.

Click on this link to read or download Advancing HIV Justice 2: Building momentum in global advocacy against HIV criminalisation.

A note about the limitations of the data

The data and case analyses in this report covers a 30-month period, 1 April 2013 to 30 September 2015. This begins where the original Advancing HIV Justice report – which covered the 18-month period, 1 September 2011 to 31 March 2013 – left off. Our data should be seen as an illustration of what may be a more widespread, but generally undocumented, use of the criminal law against people with HIV.

Justice Edwin Cameron: ‘Why HIV criminalisation is bad policy and why I’m proud that advocacy against it is being led by people living with HIV’

[This is the foreword to Advancing HIV Justice 2: Buiding momentum in global advocacy against HIV criminalisation, which will be published by the HIV Justice Network and GNP+ tomorrow, Tuesday May 10th.]

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, 35 long years ago, policymakers and politicians have been tempted to punish those of us with, and at risk of, HIV. Sometimes propelled by public opinion, sometimes themselves noxiously propelling public opinion, they have tried to find in punitive approaches a quick solution to the problem of HIV. One way has been to use HIV criminalisation – criminal laws against people living with HIV who don’t declare they have HIV, or to make potential or perceived exposure, or transmission that occurs when it is not deliberate (without “malice aforethought”), criminal offences.

Most of these laws are appallingly broad. And many of the prosecutions under them have been wickedly unjust. Sometimes scientific evidence about how HIV is transmitted, and how low the risk of transmitting the virus is, is ignored. And critical criminal legal and human rights principles are disregarded. These are enshrined in the International Guidelines on HIV and Human Rights. They are further developed by the UNAIDS guidance note, Ending overly-broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission: Critical scientific, medical and legal considerations. Important considerations, as these documents show, include foreseeability, intent, causality, proportionality, defence and proof.

The last 20 years have seen a massive shift in the management of HIV which is now a medically manageable disease. I know this myself: 19 years ago, when I was dying of AIDS, my life was given back to me when I was able to start taking antiretroviral medications. But despite the progress in HIV prevention, treatment and care, HIV continues to be treated exceptionally for one over-riding reason: stigma.

The enactment and enforcement of HIV-specific criminal laws – or even the threat of their enforcement – fuels the fires of stigma. It reinforces the idea that HIV is shameful, that it is a disgraceful contamination. And by reinforcing stigma, HIV criminalisation makes it more difficult for those at risk of HIV to access testing and prevention. It also makes it more difficult for those living with the virus to talk openly about it, and to be tested, treated and supported.

For those accused, gossiped about and maligned in the media, investigated, prosecuted and convicted, these laws can have catastrophic consequences. These include enforced disclosures, miscarriages of justice, and ruined lives.

HIV criminalisation is bad, bad policy. There is simply no evidence that it works. Instead, it sends out misleading and stigmatising messages. It undermines the remarkable scientific advances and proven public health strategies that open the path to vanquishing AIDS by 2030.

In 2008, on the final day of the International AIDS Conference in Mexico City, I called for a sustained and vocal campaign against HIV criminalisation. Along with many other activists, I hoped that the conference would result in a major international pushback against misguided criminal laws and prosecutions.

The Advancing HIV Justice 2 report shows how far we have come. It documents how the movement against these laws and prosecutions – burgeoning just a decade ago – is gaining strength. It is achieving some heartening outcomes. Laws have been repealed, modernised or struck down across the globe – from Australia to the United States, Kenya to Switzerland.

For someone like me, who has been living with HIV for over 30 years, it is especially fitting to note that much of the necessary advocacy has been undertaken by civil society led by individuals and networks of people living with HIV.

Advancing HIV Justice 2 highlights many of these courageous and pragmatic ventures by civil society. Not only have they monitored the cruelty of criminal law enforcement, acting as watchdogs, they have also played a key role in securing good sense where it has prevailed in the epidemic. This publication provides hope that lawmakers intending to enact laws propelled by populism and irrational fears can be stopped. Our hope is that outdated laws and rulings can be dispensed with altogether.

Yet this report also reminds us of the complexity of our struggle. Our ultimate goal – to end HIV criminalisation using reason and science – seems clear. But the pathways to attaining that goal are not always straightforward. We must be steadfast. We must be pragmatic. Our response to those who unjustly criminalise us must be evidence-rich and policy-sound. And we can draw strength from history. Other battles appeared “unwinnable” and quixotic. Think of slavery, racism, homophobia, women’s rights. Yet in each case justice and rationality have gained the edge.

That, we hope and believe, will be so, too, with laws targeting people with HIV for prosecution.

Edwin Cameron, Constitutional Court of South Africa, May 2016.

US: Keynote speakers announced for the HIV Is Not a Crime II National Training Academy

May 6, 2016: In just a little over a week, theHIV Is Not a Crime II National Training Academy will convene at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. There is still time toregister to train alongside committed advocates building an intersectional movement to end HIV criminalization! The Training Academy will take place from May 17 – 20, 2016.

Positive Women’s Network – USA (PWN-USA) and the SERO Project — two networks of people living with HIV — have joined forces to organize the Training Academy. We are thrilled to announce three exciting keynote speakers at the event:

- HIV community icon Mary Fisher, who spoke about her experiences living with HIV at the Republican National Convention (RNC), back in 1992;

- Longtime advocate Joel Goldman of the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation; and

- Colorado State Senator Pat Steadman, who in March introduced a bill into the state senate that would effectively repeal or significantly amend the three HIV-specific criminal codes, remove sentence enhancements for knowledge of HIV status, and modernize STI statutes to include HIV.

See below for biographical information for our speakers, in addition to highlights from the event’s dynamic program!

The Training Academy will convene in the Deep South — the region most heavily affected by not only HIV, but many other symptoms of a history steeped in injustice and trauma.

Plenary session topics include:

- What’s Working? Where Are We Struggling? Focus on State Strategies: Successes & Challenges

- AntiBlackness & HIV Criminalization: Grounding Ourselves in Racial Justice

Breakout workshop titles include:

- Activists, Advocates and Lawyers: Collaborating to a Common Goal

- Joining Forces: Mobilizing Feminists to Challenge Unjust Prosecutions

- Building Youth Capacity to Effect Policy Change Through an Intergenerational Model

Evening events include:

- Consent: HIV NonDisclosure and Sexual Assault Law, Last Men Standing, and more (film screenings)

- Advocacy, Action and Community Building Through Art

- TIME IS NOT A LINE: (re)Considering our HIV Herstory for Collective Freedom

View the full program of exciting, thought-provoking, movement-building sessions here.

HIV is a human rights issue; criminalization of people living with HIV is a social justice issue. The Training Academy will unite and train advocates living with HIV and allies from across the country on strategies and best practices for repealing laws criminalizing people living with and vulnerable to HIV. The Training Academy will also center the voices of survivors of HIV-related criminal cases and prosecutions.

Come to Huntsville and learn strategies from advocates opposing these unjust laws!

Originally published in PWN-USA website

US: The Elton John AIDS Foundation calls upon all federal, state, and local governments to put an end to the criminalisation of HIV

EJAF Chairman David Furnish: “State and Federal Governments Must Stop Criminalizing HIV”

HIV Criminalization / Michael Johnson Website Statement

May 3, 2016

Full Statement

The Elton John AIDS Foundation (EJAF) formally calls upon all federal, state, and local governments to put an end to the use of criminal law to target the conduct of people living with HIV and other diseases. In doing so, we join in consensus with a number of highly respected organizations, medical experts, public health officials, and policy makers in stating that the criminalization of HIV and other diseases institutionalizes and promotes HIV stigma and discourages people from being tested for HIV and knowing and disclosing their HIV status to their partners.

Other organizations supporting this point of view include the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, the U.S. Department of Justice, the American Medical Association, the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, the American Academy of HIV Medicine, the American Psychological Association, the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors, the National Association of County and City Health Officials, the U.S. Conference of Mayors, and the Positive Justice Project (representing more than 1000 organizational and individual endorsements from across the United States).

Recently, EJAF published a web article on the subject of the criminalization of the behavior of HIV-positive people. The Missouri case of 24-year-old Michael L. Johnson, an HIV-positive Lindenwood University star wrestler, who was sentenced to more than 30 years in prison in July of 2015 for having consensual sex with five other men, illustrates the tremendous injustice inherent in prosecuting people for being HIV positive. The men involved claim Michael did not disclose his HIV status to them, although he says he did; one man has become HIV-positive. If Michael had committed vehicular manslaughter, he would have faced a sentence of only 7 years or less. Instead, he has been given a much longer sentence drastically out of proportion to the actual harm involved.

Missouri’s law not only makes it a serious felony to have consensual sex while living with HIV, but also it explicitly states that taking measures to protect your partner by using a condom is not a defense, and it treats HIV as the equivalent of a deadly weapon, which is completely irrational. HIV is a treatable, manageable disease and should never be the basis for a felony prosecution, nor should any felony law ever refuse to take a defendant’s lack of harmful intent into consideration.

The Elton John AIDS Foundation applauds attorneys Lawrence S. Lustberg and Avram Frey of the prominent law firm of Gibbons P.C. for providing pro bono counsel for Michael’s appeal and the following organizations for signing onto an amicus brief on Michael’s behalf: AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania, American Academy of HIV Medicine, American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri Foundation, Athlete Ally, Black AIDS Institute, Center for Constitutional Rights, Center for HIV Law and Policy, Counter Narrative Project, Dr. Jeffrey Birnbaum, Empower Missouri, GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders, GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBT Equality, Grace, Human Rights Campaign, Missouri AIDS Task Force, National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors, National Black Justice Coalition, National Center for Lesbian Rights, National LGBTQ Task Force, One Struggle KC, Treatment Action Group, William Way LGBT Community Center, and Women With a Vision

Originally published on Elton John Foundation Website

US: Teleconference on HIV Criminal Laws on Thursday – May 5, 2016 from 10:30 to 11:30 a.m. ET

CHLP, The American Bar Association AIDS Coordinating Committee and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers present a teleconference on HIV Criminal Laws on Thursday, May 5 from 10:30 to 11:30 am ET on HIV Criminal Law for criminal defense lawyers, service providers in the legal, medical and social work communities and people living with HIV.

Sponsoring organizations: The ABA AIDS Coordinating Committee, The Center for HIV Law and Policy, and The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

Audience: Criminal defense lawyers, service providers in the legal, medical and social work communities and people living with HIV

Format: Interactive–speaker presentations followed by audience Q and A

Date and Time: May 5, 2016 from 10:30 to 11:30 a.m. ET

How to Participate: There is NO COST to participate. The morning of the event simply dial the Conference Call number 1 (877) 317-0419 and enter Access Code 2244415. To be sent the documents that will be referenced during the Teleconference please send your e-mail address toidominguez@nacdl.org or anichol@hivlawandpolicy.org

Summary: Thirty-four U.S. states and territories have criminal statutes that allow prosecutions for allegations of non-disclosure, exposure and (although not required) transmission of the HIV virus. Prosecutions have occurred in at least 39 states under HIV-specific criminal laws or general criminal laws. Most of these laws treat HIV exposure as a felony, and people convicted under these laws are serving sentences as long as 30 years or more. Learn from experts about these laws and how to defend against them.

Opening Remarks: Norman L. Reimer, Executive Director of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL).

Moderator: Richard A. Wilson, Chair ABA AIDS Coordinating Committee.

Presentation One: Department of Justice Civil Rights Division’s Guide to Reform HIV-Specific Criminal Laws to Align with Scientifically-Supported Factors by Allison Nichol, CHLP Co-Executive Director.

In May 2013 the United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division (CRD) issued guidance on how to reform HIV-specific criminal laws to bring them into alignment with current science, from actual routes and risks of transmission to the transformation of HIV treatment and prevention with the development of highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Presentation Two

Defending Against HIV State Law Prosecutions by Mayo Schreiber, CHLP Deputy Director.

Two recent cases in which CHLP participated, one in Missouri and one in Ohio, will be discussed, along with the HIV criminal statutes in those states. These cases and statutes are illustrative of the fundamental injustice of the statutes as drafted and the punishments provided for violating them. Defense trial and sentencing strategy will be analyzed, including identification of experts and supporting resources, and current thinking on legal challenges to these laws.

A Q&A Session Will Follow.

For more info, go to: http://www.hivlawandpolicy.org/fine-print-blog-news/when-sex-a-crime-and-spit-a-dangerous-weapon-a-teleconference-hiv-criminal-laws