AIDS is not the death sentence it once was, but Canada still has strict punishments for people who don’t disclose their HIV status to sexual partners. Critics say that’s unfair and out of step with the rest of the world. What could be done differently?

Before Michelle was diagnosed with HIV, her life was marred in ways unfathomable to most.

In the home where she grew up, drugs were dealt and intoxicated men came and went. As a young child, Michelle was sexually abused by a family member.

In the years that followed, she used alcohol, cocaine and heroin to cope. She believes she was infected with HIV in 2000 through a contaminated needle.

Struggling with addiction, Michelle turned to sex work in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. In 2006, a man accused Michelle of having unprotected sex with him without disclosing her HIV-positive status. Michelle alleges she was in an abusive, coercive relationship with the man, a former client, and that he sexually assaulted her without a condom. (The Globe and Mail does not typically name victims of sexual assault, but Michelle consented to use her first name.)

After the man brought his story to police, Michelle was charged with aggravated sexual assault. In cases involving alleged “HIV non-disclosure,” it is the charge most often laid in Canada, and the most serious sexual offence in the Criminal Code. Fearing a lengthy prison term, Michelle pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 2½ years. Only after pleading did she learn that her name had been put on the National Sex Offender Registry, something no one discussed with her in court, she said.

“I have a life sentence tied to my name,” said Michelle, now 45. “I have a label but I’m not that person. The whole label of a sex offender – I was raped at the age of 5. I know what sexual abuse is. I’m a victim of sexual abuse.”

An estimated 62,790 people were living with HIV in Canada in late 2020. Michelle is one of hundreds who’ve been prosecuted for alleged HIV non-disclosure.

Between 1989 and 2020, approximately 206 people were prosecuted in 224 criminal cases, according to a 2022 report from the HIV Legal Network. Of 187 cases where the outcome is known, 130 cases – 70 per cent – ended in conviction, the vast majority with prison time. A significant number of those convicted prior to 2023 were also registered as sex offenders, before courts ended the practice of making this mandatory for all sex offences.

In Canada, the law focuses not on actual transmission of the virus, but on “non-disclosure” – the act of not telling a sexual partner that one is HIV-positive prior to sex that poses a “realistic possibility” of transmission. This means that people who did not pass HIV to anyone have been charged, convicted and imprisoned. Of 163 cases where complainants’ HIV status was known, 64 per cent didn’t involve actual transmission of HIV. Courts have convicted HIV-positive people who took precautions before sex, as well as those who were sexually assaulted.

It is a sweeping, punitive approach that sets Canada apart from many other jurisdictions internationally.

Now, a push to limit HIV criminalization is intensifying. For years, critics have argued the laws are discriminatory and unscientific – driven by fear, misconceptions about people living with HIV and a lack of knowledge about the basic scientific realities of this virus. Thanks to significant medical advances, HIV can be managed effectively with antiretroviral medication that makes the virus undetectable and untransmittable to others.

The Canadian Coalition to Reform HIV Criminalization – a group that includes people living with HIV, community organizations, lawyers and researchers – is pushing for amendments to the Criminal Code that would limit criminal prosecution to a measure of last resort, reserved for rare cases of intentional transmission. Among other changes, the group also wants to see an end to charging these cases under sexual assault law.

“People have been prosecuted, many of whom are still living with the consequences of that prosecution, including in cases where there never should have been a charge in the first place,” said Richard Elliott, a Halifax lawyer and former executive director of the HIV Legal Network.

While the federal government has published reports, engaged in public consultations and issued some directives on limiting HIV prosecution, some advocates fear the push for broader legal reform is stalling: to date, there remains no legislation to amend this country’s HIV non-disclosure law. In the absence of legal reform, Canadians living with HIV face a lingering threat of criminal liability as they navigate their intimate lives.

Alison Symington heard about the life-altering impact of this from HIV-positive women for two documentaries she co-produced on HIV criminalization. For many of these women, the legal perils were too high to chance relationships with partners who might later turn out to be misinformed or vindictive and take them to court.

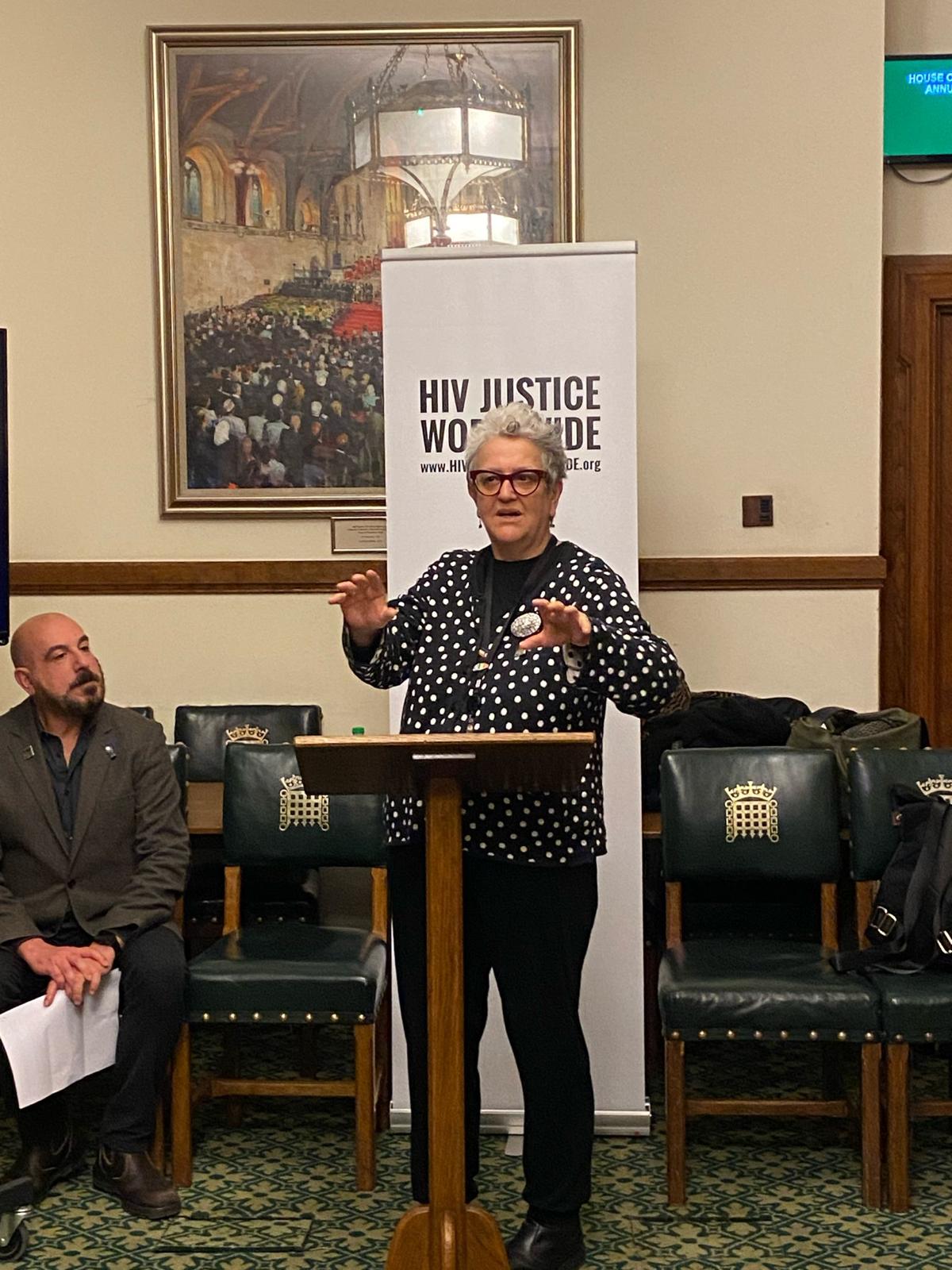

“It’s sad,” said Ms. Symington, a senior policy analyst at the HIV Justice Network. “People used to be fearful that they might pass the virus on. But now that they know they won’t pass the virus on – and that they could have a happy, healthy relationship – there’s still this outdated criminal law hanging over their heads.”

At the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the early nineties in Canada, thousands were dying of AIDS-related illnesses, many not long after a diagnosis. In 1995 alone, more than 1,700 people died, according to Statistics Canada. It was a period that would usher in some of Canada’s earliest prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure.

With the virus shrouded in panic, misinformation and stigma, some grew fearful of disclosing. But as HIV prevention campaigns took hold and AIDS activism movements began educating people on safer sex, those failing to use condoms became a minority.

The advent of effective antiretroviral treatments in 1996 transformed the landscape, with deaths dropping dramatically a year later. The drugs suppress an HIV-positive person’s viral load, making the virus undetectable and untransmittable to others. By 2020, 87 per cent of those diagnosed with HIV in Canada were on treatment, with 95 per cent of them achieving viral suppression, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Though the science progressed, both the law and public understanding of HIV failed to advance alongside.

Advocates argue the overreach in Canada’s HIV law stems partly from a 2012 Supreme Court of Canada decision, R. v. Mabior. The court ruled that HIV-positive people have a legal duty to disclose their status before having sex that poses a “realistic possibility” of HIV transmission – and decided that only a combination of condom use and a low viral load at the time of sex negate that possibility.

Critics say this legal stance diverges from well-established guidance from the World Health Organization and the Public Health Agency of Canada that a suppressed viral load or correct condom usage are each, on their own, highly effective methods of preventing transmission.

There is serious disconnect between science, public health and the law in Canada, said André Capretti, a Montreal policy analyst at the HIV Legal Network.

“Scientists have been saying undetectable equals untransmittable for many years now,” Mr. Capretti said. “But it takes a lot of time for that to permeate into the public consciousness, including at the prosecutorial level, police level and individual level. If a complainant isn’t aware that there wasn’t a risk in having sex with a partner who was undetectable, they’re still going to go to the police and want to press charges.”

Since being enacted, the laws have been used to prosecute HIV-positive people who used condoms properly and didn’t infect anyone, who engaged in oral sex – where the risk of spreading HIV is exceedingly low – and who unwittingly transmitted while being sexually assaulted. The net has caught people who are vulnerable, or who applied due diligence to not infecting others, and treated them the same as a smaller minority who transmitted recklessly.

While some court rulings are beginning to reflect the modern science on HIV transmission, other decisions have not kept up.

In 2009, an HIV-positive man in Hamilton was charged with aggravated sexual assault after his ex-partner alleged they had oral sex without the man disclosing his status. The ex-partner did not test positive; the charge was stayed in 2010.

Four years later, a Barrie, Ont., a woman was convicted of aggravated sexual assault, sentenced to more than three years in prison and registered as a sex offender for not disclosing her HIV-positive status before having vaginal sex without a condom. The woman was on antiretroviral medication, her viral load undetectable and untransmittable; her partner did not test positive. Nine years passed before her conviction was overturned, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruling that given the woman’s effective medical treatment, she was not legally obliged to disclose her status.

In 2020, the Ontario Appeals Court upheld three convictions of aggravated sexual assault for an Ontario man accused of having vaginal sex with three women without disclosing his status. There was no finding that the man infected any of the women; he wore condoms during each incident but didn’t have a low viral load during a number of those acts. The man was sentenced to 3½ years in prison.

For HIV-positive people, the prosecutions can be catastrophic.

Alexander McClelland, an assistant professor at the Institute of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Carleton University, spent time with people prosecuted for his forthcoming book, Criminalized Lives: HIV and Legal Violence.

The stories are disturbing: One man recalled being interrogated and beaten by police; another woman spoke of being locked in solitary confinement, naked. Others were vilified as HIV-positive “rapists” by prison guards, then brutalized by inmates. Some were denied HIV medication while incarcerated, growing seriously ill.

“The criminalization haunts every aspect of their lives,” said Prof. McClelland, chair of the coalition’s steering committee.

With their names broadcast through news stories and public safety warnings issued by police, many become alienated from family and friends. Others encounter employers unwilling to hire them and landlords refusing to rent to them, Prof. McClelland found.

“It isolates them in their community, where they face daily forms of harassment and violence,” he said. “These conditions ruin people’s lives.”

While prosecutions target Canadians of all genders and sexual orientations, 89 per cent of those charged were men, 63 per cent in relation to encounters they had with women. Black and Indigenous people have been disproportionately charged, convicted and incarcerated compared with white defendants. Numerous newcomers have also been deported following prosecution.

A significant proportion of those charged are heterosexual men from African, Caribbean and Black communities, according to Toronto’s Colin Johnson, who consults with Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention and the Prisoners with HIV/AIDS Support Action Network.

Some are newcomers or migrants who find themselves advised by duty counsel to plead guilty for the sake of a lesser sentence, not grasping the full scope of consequences – including the sex offender label that can follow them for the rest of their lives.

“Because in African, Caribbean and Black communities, homophobia, transphobia and HIV phobia are rampant, a lot of these people get ostracized by the very communities they would normally go to for help,” Mr. Johnson said, adding that the same stigmas keep people from getting tested and seeking treatment.

With little hope of reintegrating into society, many of these men follow a pattern from unemployment and halfway homes to isolation and depression, he said: “It’s not a pretty picture.”

Globally, Canada remains an outlier in criminalizing HIV non-disclosure. Most other countries focus instead on prosecuting people who knowingly, intentionally transmit the virus.

To lay a charge in California, for instance, prosecutors need to prove a person had specific intent to transmit HIV, and then actually transmitted the virus. In England and Wales, there is no legal obligation to disclose one’s HIV-positive status to a partner, although “reckless transmission” is illegal.

“In the case of a person who has no intent to transmit, it goes back to this notion of moral blameworthiness,” said Mr. Capretti, a human-rights lawyer. “Is this the kind of person we think is worthy of condemnation and punishment because they have this diagnosis – because they have an illness?”

Canada further deviates from other jurisdictions by charging these cases as sexual assaults.

A 1998 Supreme Court of Canada decision, R. v. Cuerrier, ruled that failing to disclose an HIV-positive status can amount to a fraud that invalidates consent – the idea being that a person can’t give consent if that consent isn’t informed. In this way, Canadian courts decided that the act of not telling is a deception on par with the violence and coercion that more often marks sexual assault.

By contrast, other countries apply general criminal law – including laws related to bodily harm – or have HIV-specific laws, according to the HIV Justice Network.

Canada has seen some movement in how these cases are handled. After former justice minister Jody Wilson-Raybould raised concerns about the overcriminalization of HIV non-disclosure, the Justice Department published a 2017 report that examined curbing such prosecutions.

Following that, in 2018, Ms. Wilson-Raybould directed federal prosecutors working in three territories to limit HIV criminalization. The directive stated officials should not prosecute HIV-positive people when they maintain a suppressed viral load because there is no realistic possibility of transmission, and that they should “generally” not prosecute when people use condoms or engage in oral sex only, because there is likely no risk of transmission. The directive also asked prosecutors to consider whether criminal charges are in the public interest.

Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia have also issued instructions not to prosecute HIV-positive people who maintained a suppressed viral load at the time of sex, though there remains no clarity on condom use.

Beyond this patchwork of directives, advocates are pushing for greater uniformity in courtrooms across Canada. They argue that the Criminal Code must be reformed – and that only this avenue will prevent courts from relying on a tangle of inconsistent and unscientific past rulings.

In 2022, the government engaged in online consultations with experts, people living with HIV and others on reviewing the law.

In March, Justice Minister Arif Virani told The Globe and Mail editorial board that his office was working on a policy response.

“What we’re trying to do is ensure that current, modern science is reflected in terms of the way the Criminal Code is applied in cases of transmission of HIV/AIDS,” Mr. Virani said, though he would not provide a timeline for legal reform.

On May 15, Mr. Virani met with the coalition to discuss law reform efforts, saying the policy work was still continuing.

Paradoxically, the blunt instrument of the law makes HIV disclosure more fraught, critics say.

“You’re starting a relationship with a new partner – you might like to know if they’re living with HIV or any other sexually transmitted diseases. But that doesn’t mean an aggravated sexual assault charge is the appropriate response,” Ms. Symington said.

In her documentaries on HIV criminalization, Ms. Symington illuminated the challenges involved in disclosing a positive status. She’s seen numerous women charged after abusive ex-partners who knew the women had HIV reported them to police for non-disclosure.

“People can make those allegations whether they’re true or not,” Ms. Symington said. “People live in fear that any relationship that goes wrong, this could be a tool of revenge by a bitter ex-partner.”

Some abusive partners exploit the law while in relationships with HIV-positive people: “Sexual partners threaten to go to the police and claim that disclosure did not take place, as a way to control the relationship,” said Eric Mykhalovskiy, a York University professor who led early research on the public-health implications of HIV non-disclosure in Ontario.

Since judges and juries tasked with deciding whether disclosure occurred have little to work with beyond complainants’ and defendants’ competing accounts, Prof. Mykhalovskiy described HIV-positive people going to great lengths to document that a disclosure had taken place, getting their partners to sign documents, disclosing with a witness present, or alongside counsellors at HIV organizations.

Inserting criminal law into nuanced discussions about negotiating consent and HIV disclosure has undermined public-health efforts, experts say: It can deter some people from getting tested or seeking out treatment, fearful that information shared with social workers, nurses and doctors could be used against them.

“We’ve seen this in so many cases of criminalization where those medical notes end up as part of the evidence used to criminally convict a person,” Mr. Capretti said.

“There is no evidence that this assists public health,” he added. “Criminal law and public-health policy are not natural partners.”

Years of criminalization has left some living with HIV fearful and frequently second guessing their intimate relationships.

It’s a calculus Toronto’s Mr. Johnson navigated in his personal life, after being diagnosed with HIV in 1984.

“I remember for years, I did not have sex with anybody unless they were HIV positive,” he said.

While he came to accept these limitations, he watched others who were just coming out struggle. News of HIV-positive people being charged in the late 80s and early 90s heightened fear, he said: “It had a negative impact on our psyche in so many ways.”

Mr. Johnson said it took him close to 20 years to accept that he would not die of AIDS-related illness. The arrival of effective antiretroviral treatments greatly improved quality of life for HIV-positive people. On the prevention front, the advent of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) significantly decreased the risk of infection among the HIV-negative.

Mr. Johnson continues antiretroviral treatment, as he has for decades. The people he dates are typically on PrEP; everyone in his circles is well aware of the modern medical realities of the virus. On his positive status, he’s transparent: “I’m very open and upfront.”

It’s a contemporary experience of living with HIV that stands in stark contrast to the public’s understanding of the virus, which remains limited.

“The average person doesn’t know about undetectable equals untransmissable, and unfortunately, with sex education these days, people aren’t going to know about that,” Ms. Symington said. “People still have Philadelphia, they still have Rock Hudson in their heads. These are the images. It causes a panic.”

These erroneous, outdated ideas should be purged from Canadian law, she said.

“This is a relic from the past. We need to stop the injustice in HIV non-disclosure and start thinking about how to educate people on healthy relationships and healthy sexual lives.”

Health and the law in Canada: More reading

B.C.’s experiment in decriminalized drug use hit a big setback last month after complaints about consumption in public. Reporter Justine Hunter spoke with The Decibel about what that means for harm-reduction policies across Canada. Subscribe for more episodes.