Translated from Original article in Russian via Deepl.com – For article in Russian, please scroll down.

In many countries, HIV-related criminal liability still exists. At least 68 countries have laws that specifically criminalize hiding information about HIV infection from your sex partner, putting another person at risk of HIV infection, or transmitting HIV. The leaders in the number of criminal cases related to HIV in the region of Eastern Europe and Central Asia are Belarus and Russia.

In 2018, 20 scientists from around the world developed an Expert Consensus Statement on the Science of HIV in the context of Criminal Law. It describes a detailed analysis of the available scientific and medical research data on HIV transmission, treatment efficacy, and evidence to better understand these data in a criminal law context.

Legislation regarding HIV transmission should be reviewed. I point out various facts to this – HIV treatment is available, antiretroviral therapy (ART) effectively reduces the viral load to undetectable and reduces the risk of HIV transmission during sexual contact to zero [1,2,3,4], criminalization initially stigmatizes people who are HIV-positive people and violates their human rights.

One of the arguments in favour of criminal liability for HIV transmission is the alleged protection of women in situations where their husbands or partners become infected with HIV. This argument is often used in Central Asian countries. Let’s look at real-life examples and statistics on how much women are actually protected by existing laws.

In early 2018, thanks to human rights defenders and human rights defenders, the article “Vikino Delo” appeared in the media, about a 17-year-old pupil of an orphanage, who was convicted under subsection 122 (1) of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation for knowingly putting another person at risk of HIV infection. In 2017, Vika met a man F. (31 years old) on a social network. When they had an intimate relationship, the girl offered to use a condom, but F. refused. Vika did not tell F. that she had HIV. From the girl’s testimony provided in court, it was clear that she did not want to put the victim at risk of infection, and did not say the diagnosis because she was afraid. She tried to hint at him, telling about her HIV-infected friend. F. proposed to be tested for HIV together. As a result, he has a minus, she has a plus. F. filed a complaint with Vic to the police. The man decided to punish the girl for insufficient, in his opinion, sincerity. Following the verdict, Vicki’s lawyer filed a complaint with the Supreme Court. On the recommendation of the Supreme Court, given that at the time of the commission of the “crime” she was a minor, apply a sentence of warning to her. At the same time, no one took the blame from her. The leading role in protecting and supporting Vicki was played by the female community in the guise of Association “EVA”.

The situation with the Vicki case is commented on by human rights activist Elena Titina, head of the Vector of Life Charity Fund, who acted as a public defender in court: “Women are subjected to even greater stigma, condemnation, and therefore do not protect themselves. Vicki’s case is very revealing in this. For three years, during the whole trial, the girl simply had to listen to insults, humiliation against her, the remarks were incorrect – and on the part of the plaintiff, this 31-year-old man, on the part of judges, prosecutors, even lawyers sometimes behaved like elephants in a china shop. She, in my opinion, is the heroine. I’m not sure that an adult woman would have endured what Vick had endured and come to the end, defending her rights. Her criminal record was removed. A unique thing, I am very proud that I participated in it. “This is the only thing that has ended so far because I don’t know of any more such precedents with a conditional happy ending. ”

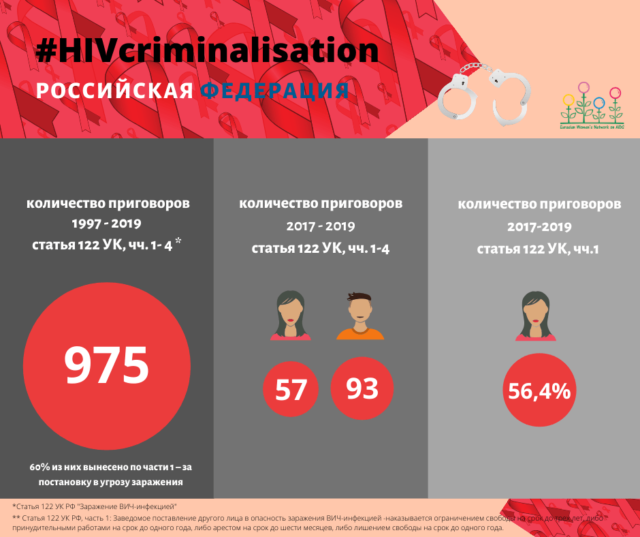

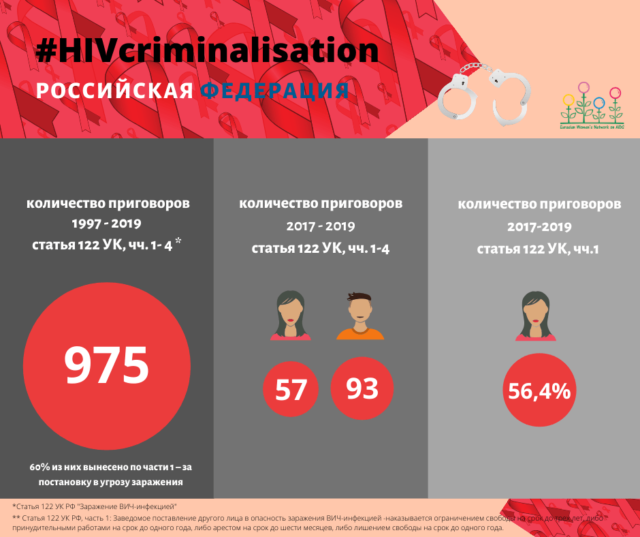

In the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation , in which almost one and a half million cases of HIV infection among citizens are only officially registered, there is article 122 “Transmission of HIV infection”. Disaggregation of data began in 2017, from 01/01/2017 to 12/31/2019, in total, within the framework of 122 articles, 150 sentences were sentenced according to the main qualification in parts 1-4. 93 sentences were pronounced against men (62%), 57 (38%) – against women. It is noteworthy that in Part 1, “Knowingly putting the other person at risk of HIV infection” is condemned by more women: 56.4% versus 43.6% of men.

According to the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Tajikistan for 2018, there were 10.7 thousand people with HIV in the whole country, of which about 7 thousand were men. It was noted that in 54.6% the virus was transmitted sexually, and in some regions, the proportion of such cases reaches 70%.

For reference: since July 2015, to register a marriage in Tajikistan, you must undergo a medical examination, which includes an HIV test.

Tajikistan became one of the few countries (and the only one in the EECA region) to which CEDAW issued a recommendation dated November 9, 2018: “Decriminalize the transmission of HIV / AIDS (Article 125 of the Criminal Code), and repeal government decrees of September 25, 2018 and October 1, 2004 years prohibiting HIV-positive women from getting a medical degree, adopting a child, or being a legal guardian. ”

Instead, on January 2, 2019, President Emomali Rahmon signed a series of laws, including those aimed at “strengthening the responsibility of doctors, beauty salons, hairdressers and service enterprises, which are due to non-compliance with sanitary, hygiene, anti-epidemic rules and regulations caused HIV / AIDS. ” From that moment, a lot of publications appeared in the media, illustrating not only the widespread informing of Tajik citizens about the requirements being followed but also the increase in the number of publications on criminal penalties related to HIV.

According to the results of media monitoring conducted by the Eurasian Women’s AIDS Network, in 2019, 23 publications on HIV were registered in the electronic media of Tajikistan. Among them, two topics were divided equally: general information on the responsibility for HIV transmission and statistics, as well as publications that women are accused of, such as:

“27-year-old woman suspected of having HIV / AIDS deliberately infecting”,

“Two women in northern Tajikistan convicted of HIV infection”,

“In Tajikistan, a woman convicted of“ deliberate HIV infection ”by 23 men was sentenced”,

“A resident of Kulyab of Tajikistan is suspected of intentionally acquiring HIV”,

“Two women in Khatlon have infected dozens of men. ”

Among these publications, there is not one that describes particular cases of men. We already wrote about the vulnerability of women in August last year in our interview with attorney Zebo Kasimova.

We could not obtain statistical data on the number of cases brought under article 125 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Tajikistan, “HIV infection”. Particularly important would be information disaggregated by sex – that is, disaggregated data, the collection of which makes special sense, in view of the state’s argument for the protection of women. The importance of disaggregated statistics is stated in the Sustainable Development Goals – the Resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2015: only accurate, reliable, comprehensive thematic data will help us understand the problems we are facing and find the most suitable solutions for them.

Olena Stryzhak, one of the founders of the Eurasian Women’s AIDS Network and the head of the Positive Women BO, is actively promoting the decriminalization of HIV in Ukraine “I have been on the committee for the second year in the validation of elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis at the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, and actively participate not only in the activities of the committee in our country but also attend international meetings of the Committee at WHO, communicate with many people working in this field.

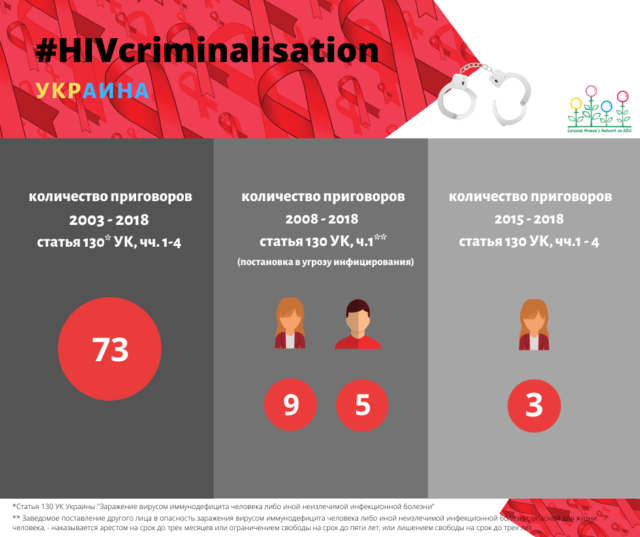

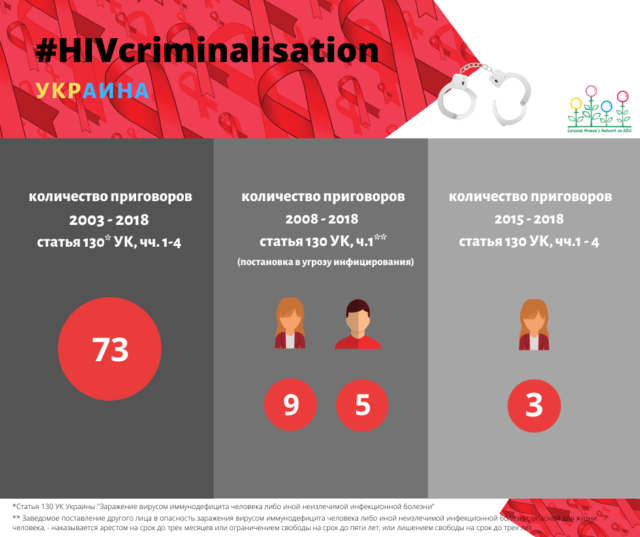

One of the obstacles for women to seek medical help and treatment on time is the fear of prosecution, the fear of possible criminal liability. In Ukraine, I was able to obtain statistics on the number of criminal cases under article 130 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, disaggregated by sex. I was surprised by the statistics, because, starting in 2015, only women were convicted under this article. This negatively affects not only the women themselves but also the effectiveness of implementing state programs, including the process of validating the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. ”

From the last case in Ukraine, for 2018: “… Since the defendant refused, the specialist for child services extended her hands to the child in order to pick her up, but the defendant bit her left hand.” From the conviction: “The court decided to qualify the actions of the defendant … Part 4 of Art. 130 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine as a complete attempt on intentional infection of another person with human immunodeficiency virus. “

Does it mean that if only women were convicted, the fact that only women are sources of infection? From an alternative shadow report of the Tajikistan Network of Women Living with HIV, presented at the 71st session of the UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in November 2018: “In violation of their rights, as a rule, women do not go anywhere. During the study of the situation when writing this report, violations of the rights of women living with HIV and women from affected groups were identified, only a few decided to defend their rights and because they were provided with a lawyer at the expense of the project. The reasons for this behaviour are different. One of the main reasons is the lack of financial resources to pay for the services of a lawyer. Secondly, many women living with HIV and women from HIV-affected groups have low legal literacy; they do not have information about who to contact on a particular issue. Thirdly, self-stigmatization and the fear of confidentiality also prevent women living with HIV and women from HIV-affected groups from defending their rights. ”

It is clear from the report that women do not defend their rights, especially on such sensitive issues, for fear of feeling even more condemned and becoming even more vulnerable. In addition, in the countries of Central Asia, families have traditions when a daughter-in-law must tell her husband or mother-in-law where she goes and what she is going to spend or spent money on (by the way about paying a lawyer). Women depend on other family members, and often do not have their own money.

Violence against women increases their risk of HIV infection, while the very presence of HIV infection in a woman also increases the risk of violence, including from relatives, due to her vulnerability and low self-esteem.

The criminalization of HIV does not work, either as a preventive measure nor as a way to protect women from infection, as decision-makers try to imagine. On the contrary, with specific examples, we observe that women are more vulnerable.

Sources:

[1] – Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11; 365: 493-505.

[2] – Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, van Lunzen J, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2016; 316: 171-81.

[3] – Grulich A, Bavinton B, Jin F, Prestage G, Zablotska, Grinsztejn B, et al. HIV transmission in male serodiscordant couples in Australia, Thailand and Brazil. Abstract for 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, USA, 2015.

[4] – Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour M, Kumarasamy N, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 1; 375 (9): 830-9.

Во многих странах все еще существует уголовная ответственность, связанная с ВИЧ. По меньшей мере 68 стран имеют законы, которые специально предусматривают уголовную ответственность за сокрытие информации о наличие ВИЧ-инфекции от своего партнера по сексу, поставление другого лица в опасность инфицирования ВИЧ или передачу ВИЧ. Лидерами по количеству уголовных дел, связанных с ВИЧ, в регионе Восточной Европы и Центральной Азии являются Беларусь и Россия.

В 2018 году, 20 ученых из разных стран мира разработали Заявление об экспертном консенсусе в отношении использования научных данных о ВИЧ в системе уголовного правосудия. В нем описан подробный анализ имеющихся данных научных и медицинских исследований о передаче ВИЧ, эффективности лечения и доказательства, позволяющие лучше понять эти данные в уголовно-правовом контексте.

Законодательные нормы в отношении передачи ВИЧ должны быть пересмотрены. На это указываю различные факты — лечение ВИЧ-инфекции доступно, антиретровирусная терапия (АРТ) эффективно снижает вирусную нагрузку до неопределяемой и снижает риски передачи ВИЧ при сексуальном контакте до нуля [1,2,3,4], криминализация изначально клеймит людей ВИЧ-положительных людей и нарушает их права человека.

Один из аргументов в пользу существования уголовной ответственности в отношении передачи ВИЧ — это якобы защита женщин, в тех ситуациях, когда их мужья или партнеры инфицируют их ВИЧ. Этот аргумент довольно часто используют в странах Центральной Азии. Давайте рассмотрим на реальных примерах и статистических данных, насколько женщины на самом деле защищены существующими законами.

В начале 2018 года, благодаря правозащитницам и правозащитникам, в СМИ появилась статья «Викино дело», о 17-ти летней воспитаннице детского дома, которую осудили по части 1 статьи 122 УК Российской Федерации за заведомое поставление другого лица в опасность заражения ВИЧ-инфекцией. В 2017 году Вика познакомилась в социальной сети с мужчиной Ф. (31 год). Когда у них была интимная связь, девушка предложила использовать презерватив, но Ф. отказался. Вика не сказала Ф., что у нее ВИЧ. Из показаний девушки, предоставленных в суде, было видно, что она не желала ставить потерпевшего в опасность заражения, и не сказала о диагнозе, потому что боялась. Она пыталась намекнуть ему, рассказывая о ВИЧ-инфицированной подруге. Ф. предложил вместе сдать анализы на ВИЧ. В результате у него — минус, у нее — плюс. Ф. подал на Вику заявление в полицию. Мужчина решил наказать девушку за недостаточную, на его взгляд, искренность. После вынесенного приговора адвокатом Вики была подана жалоба в Верховный Суд. По рекомендации Верховного Суда, учитывая, что на момент совершения «преступления» она была несовершеннолетней, применить к ней наказание в виде предупреждение. При этом вину с неё никто не снял. Ведущую роль в защите и поддержке Вики сыграло женское сообщество в лице Ассоциации “ЕВА”.

Ситуацию с делом Вики комментирует правозащитница Елена Титина, руководительница БФ «Вектор жизни», которая выступала общественой защитницей в суде: «Женщины подвергаются еще большей стигме, осуждению, поэтому не защищают себя. Дело Вики очень показательно в этом. Девочке пришлось в течение трех лет, пока длился весь судебный процесс, просто выслушивать оскорбления, унижения в свой адрес, реплики некорректные — и со стороны истца, этого 31-летнего мужчины, со стороны судей, прокуроров, даже адвокаты порой вели себя как слоны в посудной лавке. Она, на мой взгляд, героиня. Я не уверена, что взрослая женщина выдержала бы то, что выдержала Вика, и дойти до конца, защищая свои права. С нее сняли уголовную статью. Уникальное дело, я очень горжусь, что я в нем участововала. Это единственное на сегодняшний момент дело, которое так закончилось, потому что больше таких прецедентов, с условным хэппи-эндом я не знаю».

В Уголовном кодексе Российской Федерации, в которой только официально зарегистрировано почти полтора миллиона случаев ВИЧ-инфекции у граждан, существует статья 122 “Заражение ВИЧ-инфекцией”. Дезагрегация данных начата в 2017, с 01.01.2017 по 31.12.2019 всего в рамках 122 статьи вынесено 150 приговоров по основной квалификации по частям 1-4. 93 приговора вынесено в отношении мужчин (62%), 57 (38%) — в отношении женщин. Примечательно, что по части 1 “Заведомое поставление другого лица в опасность заражения ВИЧ-инфекцией” осуждается больше женщин: 56,4% против 43,6% мужчин.

По данным Министерства здравоохранения Республики Таджикистан за 2018 год, всего по стране насчитывалось 10,7 тысяч людей с ВИЧ, из них порядка 7 тысяч — мужчины. Отмечено, что в 54,6% вирус передался половым путем, а в некоторых регионах доля таких случаев достигает 70%.

Для справки: с июля 2015 года для регистрации брака в Таджикистане необходимо пройти медицинское обследование, которое включает тест на ВИЧ.

Таджикистан стал одной из немногих стран (и единственной в регионе ВЕЦА), которой КЛДЖ дал рекомендацию от 09 ноября 2018 года: “Декриминализировать передачу ВИЧ/СПИДа (статья 125 Уголовного кодекса), и отменить постановления правительства от 25 сентября 2018 года и 1 октября 2004 года, запрещающие ВИЧ-положительным женщинам получать медицинскую степень, усыновлять ребенка или быть законным опекуном”.

Вместо этого, 02 января 2019 года президент страны Эмомали Рахмон подписал ряд законов, в том числе направленных на «усиление ответственности врачей, работников салонов красоты, парикмахерских и предприятий по обслуживанию, которые из-за несоблюдения санитарно-гигиенических, санитарно-противоэпидемических правил и норм стали причиной заражения вирусом ВИЧ/СПИД». С этого момента в СМИ появилось множество публикаций, иллюстрирующих не только широкое информирование граждан Таджикистана о выполняемых предписаниях, но и увеличение количества публикаций об уголовных наказаниях в связи с ВИЧ.

По результатам медиа-мониторинга, который проводит Евразийская Женская сеть по СПИДу, в 2019 году в электронных СМИ Таджикистана зарегистрировано 23 публикации по теме ВИЧ. Среди них поровну разделили места две темы — это общая информация относительно ответственности за передачу ВИЧ и статистика, а также публикации, в которых обвиняются женщины, как, например:

“27-летняя женщина подозревается в преднамеренном заражении ВИЧ/СПИД”,

“Двух женщин на севере Таджикистана осудили за заражение ВИЧ-инфекцией”,

“В Таджикистане вынесли приговор женщине, обвиняемой в «умышленном заражении ВИЧ» 23 мужчин”,

“Жительница Куляба Таджикистана подозревается в преднамеренном заражении ВИЧ”,

“Две женщины в Хатлоне заразили десятки мужчин”.

Среди этих публикаций нет ни одной, описывающей частные случаи в отношении мужчин. Об уязвимости женщины мы уже писали в августе прошлого года в нашем интервью с адвокатессой Зебо Касимовой.

Статистические данные о количестве дел, возбужденных по статье 125 УК Республики Таджикистан, “Заражение ВИЧ-инфекцией”, нам получить не удалось. Особенно важной была бы информация с разбивкой по полу — то есть дезагрегированные данные, сбор которых имеет особый смысл, ввиду аргументации государства о защите женщин. О важности дезагрегированной статистики говорится в Целях устойчивого развития — Резолюции, принятой Генеральной Ассамблеей ООН в 2015 году: только точные, достоверные, всесторонние тематические данные позволят понять проблемы, стоящие перед нами, и найти для них самые подходящие решения.

Елена Стрижак, одна из основательниц Евразийской Женской Сети по СПИДу и руководительница БО “Позитивные женщины”, активно продвигает тему декриминализации ВИЧ в Украине: “Я уже второй год состою в комитете по валидации элиминации передачи ВИЧ и сифилиса от матери к ребенку при Министерстве здравоохранение Украины, и активно принимаю участие не только в деятельности комитета в нашей стране, но и посещаю международные заседания Комитета в ВОЗ, общаюсь со многими людьми, работающими в этой сфере.

Одним из препятствий к тому, чтобы женщины вовремя обращались за медицинской помощью и за лечением, служит страх обвинения, страх перед возможной криминальной ответственностью. У нас в Украине я смогла получить статистические данные о количестве уголовных дел по статье 130 УК Украины, с разбивкой по полу. Была удивлена статистикой, потому что, начиная с 2015 года, по этой статье были осуждены исключительно женщины. Это негативно отражается не только на самих женщинах, но и на эффективности реализации государственных программ, в том числе на процессе валидации элиминации передачи ВИЧ от матери к ребенку”.

Из последнего кейса по Украине, за 2018 год: «…Так как подсудимая отказалась, специалист службы по делам детей протянула руки к ребенку с целью забрать ее, но подсудимая укусила ее за левую руку». Из обвинительного приговора: «Суд принял решение квалифицировать действия подсудимой … ч. 4 ст. 130 УК Украины как оконченное покушение на умышленное заражение другого лица вирусом иммунодефицита человека».

Означает ли, что если осужденными оказались только женщины, тот факт, что только женщины являются источниками инфицирования? Из альтернативного теневого доклада Таджикистанской сети женщин, живущих с ВИЧ, представленного на 71-й сессии Комитета ООН по ликвидации всех форм дискриминации в отношении женщин в ноябре 2018 года: “При нарушении их прав, как правило, женщины никуда не обращаются. В ходе изучения ситуации при написании данного отчета выявлены нарушения прав женщин, живущих с ВИЧ, и женщин из затронутых групп, только единицы решились защищать свои права и то, потому что им был предоставлен адвокат за счет проекта. Причины такого поведения различны. Одна из основных причин, это отсутствие финансовых средств на оплату услуг адвоката. Во-вторых, многие женщины, живущие с ВИЧ, и женщины из затронутых ВИЧ групп имеют низкую правовую грамотность, у них нет информации о том, к кому обратиться по тому или иному вопросу. В-третьих, самостигматизация и боязнь разглашения конфиденциальности также мешает женщинам, живущим с ВИЧ, и женщинам из затронутых ВИЧ групп защищать свои права.”

Из доклада ясно, что женщины не защищают свои права, особенно по таким чувствительным вопросам, из-за страха почувствовать еще больше осуждения и стать еще более уязвимыми. Кроме того, в странах Центральной Азии, в семьях есть традиции, когда невестка должна сказать мужу или свекрови, куда она идет, и на что она собирается тратить или потратила деньги (к слову об оплате адвоката). Женщины зависят от других членов семьи, и часто не имеют своих собственных денег.

Насилие в отношении женщин увеличивает для них риск инфицирования ВИЧ, в то же время само наличие ВИЧ-инфекции у женщины также увеличивает опасность насилия, в том числе и со стороны родственников, из-за ее уязвимости и заниженной самооценки.

Криминализация ВИЧ, ни как превентивная мера, ни как способ защиты женщин от инфицирования не работает, как это пытаются представить люди, принимающие решения. Наоборот, на конкретных примерах мы наблюдаем, что женщины оказываются более уязвимыми.

Источники:

[1] — Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11; 365:493-505.

[2] — Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, van Lunzen J, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2016; 316:171-81.

[3] — Grulich A, Bavinton B, Jin F, Prestage G, Zablotska, Grinsztejn B, et al. HIV transmission in male serodiscordant couples in Australia, Thailand and Brazil. Abstract for 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, USA, 2015.

[4] — Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour M, Kumarasamy N, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 1; 375(9):830-9.