To celebrate the 9th anniversary of the Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation, the HIV Justice Network’s web show for advocates and activists, HIV Justice Live!, will this week feature some of the civil society activists who were behind the influential global call for a cohesive, evidence-informed approach to the use of criminal law relating to HIV non-disclosure, exposure, and transmission.

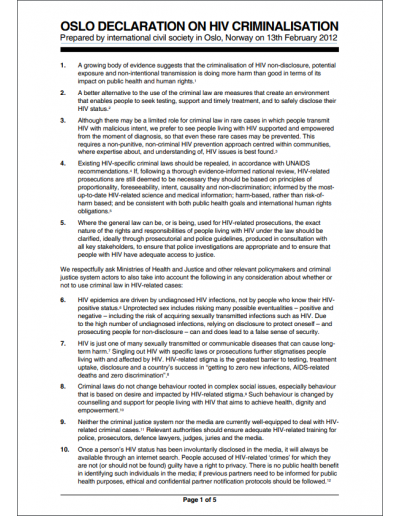

On February 13, 2012, a group of individuals from civil society around the world, concerned about the inappropriate and overly broad use of the criminal law to regulate and punish people living with HIV for behaviour that in any other circumstance would be considered lawful, came together in Oslo to create the Declaration.

The meeting took place on the eve of the global High-Level Policy Consultation on the Science and Law of the Criminalisation of HIV Non-disclosure, Exposure and Transmission, convened by the Government of Norway and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

The Oslo Declaration, published on the brand new hivjustice.net website on February 22, 2012, became the founding document of the HIV Justice Network. Within weeks, more than 1700 supporters from more than 115 countries had signed up to the Declaration, creating a network of diverse activists, all fighting for #HIVJustice.

Now, nine years later, HIV Justice Live! will meet some of the advocates behind this historic statement including former ARASA Executive Director, Michaela Clayton, now a member of HJN’s Supervisory Board; former Senior Human Rights and Law Adviser at UNAIDS in Geneva, Patrick Eba, now UNAIDS Country Director in the Central African Republic; HIV activist Kim Fangen, a former member of the Norwegian Law Commission and co-organiser of the Oslo Declaration meeting; and Ralf Jürgens, co-founder of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, now Senior Coordinator of Human Rights at The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria.

HJN’s Executive Director, Edwin J Bernard, who co-organised the meeting that created the Oslo Declaration with Kim Fangen will be discussing the importance of the Declaration as well as taking stock of developments around HIV criminalisation globally over the past decade.

HIV Justice Live! will be streamed on the HJN’s Facebook and YouTube channel on February 17, 2021, at 6 pm CET.