A remarkable amount of advocacy and information sharing took place during the XVIII International AIDS Conference held in Vienna last month. Over the next few blog posts, I’ll be highlighting as much as I can starting with a round-up of sessions, meetings, and media reports from the conference. A separate blog post will highlight posters, a movie screening and some inspirational personal meetings.

Sunday: Criminalisation of HIV Exposure and Transmission: Global Extent, Impact and The Way Forward

A meeting that I co-organised (representing NAM) along with the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+) and the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network received quite a lot of coverage.

Criminalisation of HIV Exposure and Transmission: Global Extent, Impact and The Way Forward was a great success with many of the 80+ attendees telling me it was Vienna highlight. The entire meeting, lasting around 2 1/2 hours, has been split into eight videos: an introduction; six presentations; and an audience and panel discussion. The entire meeting can also be viewed at the NAM and Legal Network websites, with GNP+ soon to follow.

Reports from the meeting focusing on different parts of the meeting were filed by NAM and NAPWA (Aus) and I was interviewed by Mark S King for his video blog for thebody.com.

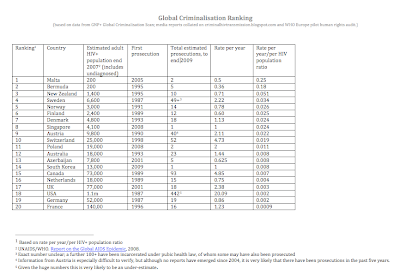

Richard Elliott of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, Moono Nyambe from GNP+ and UNAIDS’ Susan Timberlake – all of whom took part in the meeting – were interviewed for a piece in Canada’s Globe and Mail, with the headline, U.S., Canada lead world in prosecuting those who transmit AIDS virus: Criminal charges are justified only when infection is intentional, activists contend.

The same day, an editorial in the Globe and Mail completely undermined the rather balanced article by stating, quite bluntly

Disclosing one’s status is, of course, a difficult and emotional journey, fraught with potentially negative consequences. HIV-positive people can be marginalized, and discriminated against in terms of housing, employment and social relationships. However, the collective rights of this minority group cannot take precedence over their individual responsibility not to infect others.

It concluded

But in Canada the law is clear: Exposure without disclosure is a crime. And that is a good thing.

Judging by the comments left by readers of both articles, although there is some sympathy for the person with HIV, there’s a long way to go before Canadian hearts and minds are won over by the anti-criminalisation advocacy movement.

Wednesday: Policing Sex and Sexuality: The Role of Law in HIV

Lucy Stackpool-Moore (IPPF) and Mandeep Dhaliwal (UNDP)co-chaired a satellite session on the Wednesday that included presentations by Anand Grover, UN Special Rapporteur on Right to Health, and my colleague Robert James of Birkbeck College, University of London.

Thursday: HIV and Criminal Law: Prevention or Punishment?

This debate included discussion of criminalisation from the point of view of increased stigma. Lucy Stackpool-Moore again contributed. The session was not only recorded by the rapporteur, Skhumbuzo Maphumulo, but also reported on by PLUS News.

Thursday: Leaders against Criminalization of Sex Work, Sodomy, Drug Use or Possession, and HIV Transmission

This was the session with the highest profile names (rapporteur summary

here). Chaired by Stephen Lewis, Founder of AIDS Free World, it was left to none other than Festus Mogae, Former President of Botswana, and a member of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, to make a statement against the criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission: “Criminalisation of HIV transmission is…futile”, he said, quite a few times. (Audio of his statement, at around 38:00, can be heard

here).

Although it was mostly a repetition of some of the well-worn public health and human rights reasons already presented two years earlier by

Edwin Cameron at AIDS 2008, it is significant that a former president of an African country made this statement, given the

‘legislation contagion‘ that has occurred on that continent. President Mogae noted that he had written to some of his estwhile colleagues pleading with them not to pass HIV-specific laws in their countries. With more than 25 African countries with such laws on the statute books and at least another eight African countries considering them, I think they need some more convincing.

This was the only oral abstract session at AIDS 2010 dedicated exclusively to the criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission, and I was honored to have two abstracts represented. The rapporteur summary is

here.

I’ve already included a blog posting on my presentation, which you can see here. The other presentations included Criminalization of HIV transmission and exposure and obligatory testing in 8 Latin American countries, presented by Tamil Rainanne Kendall. (Audio and slides here); Tanzania case study on how AIDS law criminalizes stigma and discrimination but also stigmatizes by criminalizing deliberate HIV infection, presented by Millicent Obaso (Audio and slides here); and If there is no risk and no harm there should be no crime. Legal, evidential and procedural approaches to reducing unwarranted prosecutions of people with HIV for exposure and transmission, presented by Robert James (and co-authored by yours truly). (Audio and slides here).

The session was also reported on by aidsmap.com.

Thursday: Late Breakers (Track F)

This session included three oral abstracts on criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission.

A quantitative study of the impact of a US state criminal HIV disclosure law on state residents living with HIV, presented by Carol Galletly. (Audio and slides here).

Roger Pebody of aidsmap.com provides an excellent summary of her findings here

Under [Michigan] state legislation, people with HIV are legally obliged to disclose their HIV status before any kind of sexual contact. Disclosure is meant to occur before sexual intercourse “or any other intrusion, however slight, of any part of a person’s body or of any object into the genital or anal openings of another person’s body”. This would include even fingering or the use of a sex toy.

Carol Galletly reported on a study with 384 people with HIV who live in Michigan (but recruitment methods and demographics were not fully described). Three quarters of respondents were aware of the law.

She wanted to see if the existence of the law had any impact on her respondents’ behaviour. Comparing those who were aware of the law with those who were not, people who knew about the law were no more likely to disclose their HIV status to sexual partners. Moreover they were not less likely to have risky sex.

On the other hand, approximately half of participants believed that the law made it more likely that people with HIV would disclose to sex partners. Having this belief was associated with being a person who did disclose HIV status to partners.

In fact a majority of participants supported the law. Individuals who Gallety characterised as possibly being marginalised were more likely to support the law: women, non-whites, people with less education and people with a lower income.

The two other presentations were: HIV non-disclosure and the criminal law: effects of Canada’s ‘significant risk’ test on people living with HIV/AIDS and health and social service providers, presented by Eric Mykhalovskiy (Audio and slides here) and Advocating prevention over punishment: the risks of HIV criminalization in Burkina Faso presented by Patrice Sanon (Audio and slides here).

Other media reports

Other reports mentioning the criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission published during the conference include:

A piece in the Montreal Gazette, headlined, Advocates raise concerns over prosecuting HIV-positive people

The troubling increase in the number of new HIV cases in Canada may be attributed to the country’s reputation of being a world leader in prosecuting HIV-positive people who fail to disclose their status, according to one group of AIDS advocates. “We’re looking at rising numbers of infection, especially among certain risk groups,” said Ron Rosenes, vice chair of Canadian Treatment Action Council. “And now we’re looking at the criminalization issue as one of the reasons people have been afraid to learn their status.”

Totally unproven, of course, but a great hook to hang the story on.

There was also a round-up story focusing on the broader issue of criminalisation (of drug use, same-sex sex, sex work) that mentioned HIV exposure and transmission in passing on

this blog post on RH Reality Check.

Finally,

an article in CMAJ interviewed Richard Elliott (again!) and highlighted some of the advocacy work at AIDS 2010 as it discussed the ongoing debate in Canada regarding the use of the criminal law to prosecute non-disclosure.