On 17 February 2011, Denmark’s Minister of Justice announced the suspension of Article 252 of the Danish Criminal Code. This law is reportedly the only HIV-specific criminal law provision in Western Europe and has been used to prosecute some 18 individuals.

Edwin J Bernard’s Keynote at Funders Concerned About AIDS: ‘Combating HIV Criminalization at Home & Abroad’ (2010)

Edwin J Bernard’s keynote presentation at the Funders Concerned About AIDS 2010 Philanthropy Summit, Washington DC, December 6 2010.

The slides for this presentation are available to donwload (as a pdf) here: bit.ly/fcaadec10

Limiting the Law: Silence, Sex and Science (Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, 2010)

A community forum on the criminalization of HIV in Canada

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Toronto, Ontario

Presentations by:

Edwin J. Bernard, British HIV-positive writer, editor and activist; editor, HIV and the Criminal Law and “Criminal HIV Transmission” blog

Richard Elliott, Executive Director, Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network

Eric Mykhalovskiy, Associate Professor, York University, Department of Sociology

Tim McCaskell, The Ontario Working Group on Criminal Law and HIV Exposure

Rai Reese, Women’s Prisons Program Coordinator, Prisoners’ HIV/AIDS Support Action Network

US: Positive Justice Project launches, aims to remove HIV-specific laws

Press Release: HIV Advocacy Group Launches Positive Justice Project To Fight Stigma and Discrimination by Repealing HIV-specific Criminal Statutes

The Positive Justice Project, a campaign of the Center for HIV Law and Policy, was launched this week to combat HIV-related stigma and discrimination against people with HIV by the criminal justice system. A day-long organising meeting, held September 21st in New York, included more than 40 participants from legal, government, grant-making and community service organisations.

The focus of the Positive Justice Project is the repeal of “HIV criminalisation” statutes — laws that create HIV-specific crimes or which increase penalties for persons who are HIV-positive and convicted of criminal offences.

The Positive Justice Project is the first coordinated national effort in the United States to address these laws, and the first multi-organizational and cross-disciplinary effort to do so. HIV criminalisation has often resulted in gross human rights violations, including harsh sentencing for behaviors that pose little or no risk of HIV transmission, including:

- A man with HIV in Texas who is now serving 35 years for spitting at a police officer;

- A man with HIV in Iowa, who had an undetectable viral load, was sentenced to 25 years after a one-time sexual encounter during which he used a condom;

- A woman with HIV in Georgia, who was sentenced to eight years imprisonment for failing to disclose her viral status, despite it having been published on the front page of the local newspaper and two witnesses who testified her sexual partner was aware of her HIV-positive status;

- And a man with HIV in Michigan who was charged under the state’s anti-terrorism statute with possession of a “biological weapon,” after an altercation with a neighbour.

In none of the cases cited was HIV transmitted. Actual HIV transmission—or even the intent to infect—is rarely a factor in HIV criminalisation cases.

Instead, most prosecutions are not for HIV transmission, but for the failure to disclose one’s HIV status prior to intimate contact, which in most cases comes down to competing claims about verbal consent that are nearly impossible to prove. Anti-criminalisation advocates support prosecution only in cases where the intent to harm can be proven.

HIV criminalisation undercuts the most basic HIV prevention and sexual health message, which is that each person must be responsible for his or her own sexual choices and health. Criminalisation implies a disproportionate responsibility, providing an illusion of safety to the person who is HIV-negative or who does not know his or her HIV status.

As a result, ignorance of one’s HIV status is the best defence against prosecution in these cases, ultimately providing a disincentive to testing and self-awareness. Only by getting an HIV test and knowing one’s HIV status is one subject to arrest and prosecution. This flies in the face of established evidence that it is those who are untested – i.e., those who are safe from prosecution – who most frequently transmit HIV.

Research has demonstrated that HIV criminalisation statutes do nothing to reduce HIV transmission and, in fact, because they further stigmatise already-marginalised populations and discourage HIV testing, they may contribute to further HIV transmission.

The Center for HIV Law and Policy also this week released a draft of the first detailed analysis of HIV-specific laws and prosecutions in all 50 states, U.S. territories and the military. With more than 400 prosecutions to date, the U.S. has had more HIV-specific criminal cases than any other nation on earth.

According to the Positive Justice Project organisers, the challenge of repealing laws that punish people on the basis of their HIV status cannot be met without:

- Broader public understanding of the stigmatising impact and negative public health consequences of criminalisation statutes and prosecutions that are perpetrated under their guise;

- Greater community consensus on the appropriate use of criminal and civil law in the context of the HIV epidemic;

- Clear, unequivocal leadership and statements from federal, state and local public health officials on the causes and relative risks of HIV transmission and the dangers of a punitive response to HIV exposure and the epidemic;

- And a broader and more effective community-level response to the ongoing problem of HIV-related arrests and prosecutions.

“Misperceptions about the routes and risks of HIV transmission continue to fuel fear and myths about people with HIV that leads to lower acceptance of HIV testing and greater stigma and discrimination. Nearly 30 years into the epidemic, people still fear contact with people with HIV, working with them or allowing them near their children,” said Catherine Hanssens, the founder and executive director of the Center for HIV Law and Policy.

“HIV-specific laws have created a viral underclass. There is no more extreme manifestation of stigma than when it is enshrined in the law,” said Sean Strub, who has lived with HIV for more than 30 years. Strub is a senior advisor with the Center for HIV Law and Policy and joined in launching the Positive Justice Project.

Vanessa Johnson, a Positive Justice Project planning committee member and Executive Vice President of the National Association of People with AIDS, said, “When the government uses the fact of a person’s HIV test and subsequent result to turn around and encourage prosecution of that person for behavior that otherwise is legal for people who are untested, it engages in dangerously confusing double-speak that undermines the very HIV testing and prevention goals it claims to prioritize.”

Global: HIV and the criminal law book now available; hear me speak in Ottawa and Toronto

The next few weeks sees my involvement in a flurry of anti-criminalisation advocacy in the United States and Canada, coinciding with the publication of the book version of the new international resource I produced for NAM and an article in HIV Treatment Update summarising the current global situation.

HIV and the Criminal Law

|

||

| Email: info@nam.org.uk to order a copy |

Preface by The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG and Edwin Cameron, Justice of the Constitutional Court of South Africa.

Introduction How this resource addresses the criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission.

Fundamentals An overview of the global HIV pandemic, and the role of human rights and the law in the international response to HIV.

Laws A history of the criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission, and a brief explanation of the kinds of laws used to do this.

Harm Considers the actual and perceived impact of HIV on wellbeing, how these inform legislation and the legal construction of HIV-related harm.

Responsibility Looks at two areas of responsiblity for HIV prevention: responsibility for HIV-related sexual risk-taking and responsibility to disclose a known HIV-positive status to a sexual partner.

Risk An examination of prosecuted behaviours, using scientific evidence to determine actual risk, and how this evidence has been applied in jurisdictions worldwide.

Proof Foreseeability, intent, causality and consent are key elements in establishing criminal culpability. The challenges and practice in proving these in HIV exposure and transmission cases.

Impact An assessment of the impact of criminalisation and HIV – on individuals, communities, countries and the course of the global HIV epidemic.

Details: international resource and individual country data A summary of laws, prosecutions and responses to criminalisation of HIV exposure or transmission internationally, and key sources of more information.

HIV Treatment Update

The August/September issue of NAM’s newsletter, HIV Treatment Update, features a 2500 word article, ‘Where HIV is a Crime, Not Just a Virus’, that examines the current state of criminalisation internationally.

Here’s the first part: click on the image to download the complete article.

Since 1987, when prosecutions in Germany, Sweden and the United States were first recorded, an increasing number of countries around the world have applied existing criminal statutes or created HIV-specific criminal laws to prosecute people living with HIV who have, or are believed to have, put others at risk of acquiring HIV.

Most of the prosecutions have been for consensual sexual acts, with a minority for behaviour such as biting and spitting.

In the majority of these cases, HIV transmission did not occur; rather, someone was exposed to the risk of acquiring HIV without expressly being informed by the person living with HIV that there was a risk of HIV exposure.

In the cases where someone did test positive for HIV, proof that the defendant intended to harm them and/or was the source of the infection has often been less than satisfactory.

South Africa’s openly HIV-positive Constitutional Court Justice, Edwin Cameron, called for a global campaign against criminalisation at the 17th International AIDS Conference in Mexico City in 2008, declaring: “HIV is a virus, not a crime.”

Two years later, the discussion for people working in the HIV sector has moved on from a debate about whether such laws and prosecutions are good or bad public policy to one on how to turn the tide and mitigate the harm of criminalisation. Most of them advocate, in the long term, for decriminalisation of all acts other than clearly intentional HIV transmission. This, however, is a debate that many people outside the HIV sector have yet to even start.

Next Tuesday, September 21st, I’ll be joining a group of US anti-criminalisation advocates for a meeting in New York to discuss how to move towards mitigating the harm of US disclosure laws and prosecutions for HIV exposure and non-intentional transmission.

The goals of the Positive Justice Project campaign include:

- Broader public understanding of the stigmatizing impact and other negative public health consequences of criminalization and other forms of discrimination against people with HIV that occur under the guise of addressing HIV transmission.

- Community consensus on the appropriate use of criminal and civil law in the context of the HIV epidemic.

- Clear statements from lead government officials on the causes and relative risks of HIV transmission and the dangers of a criminal enforcement response to HIV exposure and the epidemic.

- A broader, more effective community-level response to the ongoing problem of HIV-related arrests and prosecutions.

- Reduction and eventual elimination of the inappropriate use of criminal and civil punishments against people with HIV.

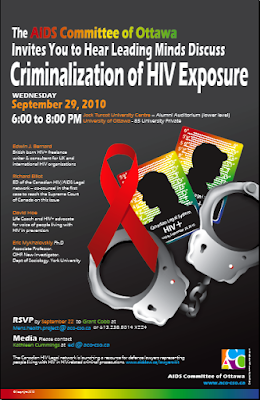

Ottawa: September 29th 6pm-8pm

|

| Click on the flyer to download |

I’ll be in Canada’s capital, Ottawa, on Wednesday September 29th to speak about my experiences of blogging on criminalisation worldwide, and to provide examples of international anti-criminalisation advocacy that Canadian advocates might find useful in their fight against the ramping up of charges for non-disclosure and the irrational and scare-mongering response to accusations of non-disclosure from law enforcement.

Ottawa has become ground zero for anti-criminalisation advocacy in recent months following the arrest and public naming and shaming of a gay man for non-disclosure. Following community outrage at the man’s treatment, the Ottawa Police Service Board rejected calls to develop guidelines for prosecution for HIV non-disclosure cases.

The meeting will also feature several leading lights in Canadian, if not global, anti-criminalisation advocacy: Richard Elliott, Executive Director of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network; HIV-positive advocate David Hoe; and Eric Mykhalovskiy, Associate Professor at York University, Department of Sociology.

Toronto: September 30th 6.30pm-8.30pm

|

| Click on image for link to Facebook event page |

The following day, Richard, Eric, myself and a fourth panellist (TBC) will be presenting at Silence, Sex and Science, Thursday, September 30, 2010, 6:30 to 8:30 pm at Oakham House, 55 Gould Street, Toronto.

I hope to meet any blog readers who can make it to either of the Canadian meetings, and will, of course, be posting more about these meetings in the future.

Global: AIDS 2010 round-up part 2: Posters

This selection of posters presented in Vienna follows up from my previous AIDS 2010 posting on the sessions, meetings and media reporting that took place during last month’s XVIII International AIDS Conference. I’ll be a highlighting a few others in later blog posts, but for now here’s three posters that highlight how the law discriminates; why non-disclosure is problematic to criminalise; and how political advocacy can sometimes yield positive change.

In Who gets prosecuted? A review of HIV transmission and exposure cases in Austria, England, Sweden and Switzerland, (THPE1012) Robert James examines which people and which communicable diseases came to the attention of the criminal justice system in four European countries, and concludes: “Men were more likely than women to be prosecuted for HIV exposure or transmission under criminal laws in Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. The majority of cases in Austria involved the prosecution of female sex workers. Migrants from southern and west African countries were the first people prosecuted in Sweden and England but home nationals have now become the largest group prosecuted in both countries. Even in countries without HIV specific criminal laws, people with HIV have been prosecuted more often than people with more common contagious diseases.”Download the pdf here.

In Responsibilities, Significant Risks and Legal Repercussions: Interviews with gay men as complex knowledge-exchange sites for scientific and legal information about HIV (THPE1015), Daniel Grace and Josephine MacIntosh from Canada interviewed 55 gay men, some of whom were living with HIV, to explore issues related to the criminalisation of non-disclosure, notably responsibilities, significant risks and legal repercussions. Their findings highlight why gay men believe that disclosure is both important and highly problematic. Download the pdf here.

In Decriminalisation of HIV transmission in Switzerland (THPE1017), Luciano Ruggia and Kurt Pärli of the Swiss National AIDS Commission (EKAF) – the Swiss statement people – describe how they have been working behind the scenes to modify Article 231 of the Swiss Penal Code which allows for the prosecution by the police of anyone who allegedly spreads “intentionally or by neglect a dangerous transmissible human disease” without the need of a complainant. Disclosure of HIV-positive status and/or consent to unprotected sex does not preclude this being an offence, in effect criminalising all unprotected sex by people with HIV. Since 1989, there have been 39 prosecutions and 26 convictions under this law. A new Law on Epidemics removes Article 231, leaving only intentional transmission as a criminal offence, and will be deabted before the Swiss Parliament next year. Download the pdf here.

Global: AIDS 2010 round-up part 1: sessions, meetings and media reports

A remarkable amount of advocacy and information sharing took place during the XVIII International AIDS Conference held in Vienna last month. Over the next few blog posts, I’ll be highlighting as much as I can starting with a round-up of sessions, meetings, and media reports from the conference. A separate blog post will highlight posters, a movie screening and some inspirational personal meetings.

Sunday: Criminalisation of HIV Exposure and Transmission: Global Extent, Impact and The Way Forward

A meeting that I co-organised (representing NAM) along with the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+) and the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network received quite a lot of coverage.

Criminalisation of HIV Exposure and Transmission: Global Extent, Impact and The Way Forward was a great success with many of the 80+ attendees telling me it was Vienna highlight. The entire meeting, lasting around 2 1/2 hours, has been split into eight videos: an introduction; six presentations; and an audience and panel discussion. The entire meeting can also be viewed at the NAM and Legal Network websites, with GNP+ soon to follow.

Reports from the meeting focusing on different parts of the meeting were filed by NAM and NAPWA (Aus) and I was interviewed by Mark S King for his video blog for thebody.com.

Richard Elliott of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, Moono Nyambe from GNP+ and UNAIDS’ Susan Timberlake – all of whom took part in the meeting – were interviewed for a piece in Canada’s Globe and Mail, with the headline, U.S., Canada lead world in prosecuting those who transmit AIDS virus: Criminal charges are justified only when infection is intentional, activists contend.

The same day, an editorial in the Globe and Mail completely undermined the rather balanced article by stating, quite bluntly

Disclosing one’s status is, of course, a difficult and emotional journey, fraught with potentially negative consequences. HIV-positive people can be marginalized, and discriminated against in terms of housing, employment and social relationships. However, the collective rights of this minority group cannot take precedence over their individual responsibility not to infect others.

It concluded

But in Canada the law is clear: Exposure without disclosure is a crime. And that is a good thing.

Judging by the comments left by readers of both articles, although there is some sympathy for the person with HIV, there’s a long way to go before Canadian hearts and minds are won over by the anti-criminalisation advocacy movement.

Wednesday: Policing Sex and Sexuality: The Role of Law in HIV

Lucy Stackpool-Moore (IPPF) and Mandeep Dhaliwal (UNDP)co-chaired a satellite session on the Wednesday that included presentations by Anand Grover, UN Special Rapporteur on Right to Health, and my colleague Robert James of Birkbeck College, University of London.

Thursday: HIV and Criminal Law: Prevention or Punishment?

This debate included discussion of criminalisation from the point of view of increased stigma. Lucy Stackpool-Moore again contributed. The session was not only recorded by the rapporteur, Skhumbuzo Maphumulo, but also reported on by PLUS News.

Thursday: Leaders against Criminalization of Sex Work, Sodomy, Drug Use or Possession, and HIV Transmission

I’ve already included a blog posting on my presentation, which you can see here. The other presentations included Criminalization of HIV transmission and exposure and obligatory testing in 8 Latin American countries, presented by Tamil Rainanne Kendall. (Audio and slides here); Tanzania case study on how AIDS law criminalizes stigma and discrimination but also stigmatizes by criminalizing deliberate HIV infection, presented by Millicent Obaso (Audio and slides here); and If there is no risk and no harm there should be no crime. Legal, evidential and procedural approaches to reducing unwarranted prosecutions of people with HIV for exposure and transmission, presented by Robert James (and co-authored by yours truly). (Audio and slides here).

The session was also reported on by aidsmap.com.

Thursday: Late Breakers (Track F)

This session included three oral abstracts on criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission.

A quantitative study of the impact of a US state criminal HIV disclosure law on state residents living with HIV, presented by Carol Galletly. (Audio and slides here).

Roger Pebody of aidsmap.com provides an excellent summary of her findings here

Under [Michigan] state legislation, people with HIV are legally obliged to disclose their HIV status before any kind of sexual contact. Disclosure is meant to occur before sexual intercourse “or any other intrusion, however slight, of any part of a person’s body or of any object into the genital or anal openings of another person’s body”. This would include even fingering or the use of a sex toy.

Carol Galletly reported on a study with 384 people with HIV who live in Michigan (but recruitment methods and demographics were not fully described). Three quarters of respondents were aware of the law.

She wanted to see if the existence of the law had any impact on her respondents’ behaviour. Comparing those who were aware of the law with those who were not, people who knew about the law were no more likely to disclose their HIV status to sexual partners. Moreover they were not less likely to have risky sex.

On the other hand, approximately half of participants believed that the law made it more likely that people with HIV would disclose to sex partners. Having this belief was associated with being a person who did disclose HIV status to partners.

In fact a majority of participants supported the law. Individuals who Gallety characterised as possibly being marginalised were more likely to support the law: women, non-whites, people with less education and people with a lower income.

The two other presentations were: HIV non-disclosure and the criminal law: effects of Canada’s ‘significant risk’ test on people living with HIV/AIDS and health and social service providers, presented by Eric Mykhalovskiy (Audio and slides here) and Advocating prevention over punishment: the risks of HIV criminalization in Burkina Faso presented by Patrice Sanon (Audio and slides here).

Other media reports

Other reports mentioning the criminalisation of HIV exposure and transmission published during the conference include:

A piece in the Montreal Gazette, headlined, Advocates raise concerns over prosecuting HIV-positive people

The troubling increase in the number of new HIV cases in Canada may be attributed to the country’s reputation of being a world leader in prosecuting HIV-positive people who fail to disclose their status, according to one group of AIDS advocates. “We’re looking at rising numbers of infection, especially among certain risk groups,” said Ron Rosenes, vice chair of Canadian Treatment Action Council. “And now we’re looking at the criminalization issue as one of the reasons people have been afraid to learn their status.”

Global: ‘Where HIV is a crime, not just a virus’ – updated Top 20 table and video presentation now online

Where HIV Is a Crime, Not Just a Virus from HIV Action on Vimeo.

Here is my presentation providing a global overview of laws and prosecutions at the XVIII International AIDS Conference, Vienna, on 22 July 2010.

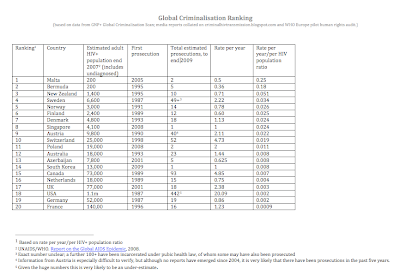

Abstract: Where HIV is a crime, not just a virus: a global ranking of prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

Issues: The global (mis)use of the criminal law to control and punish the behaviour of PLHIV was highlighted at AIDS 2008, where Justice Edwin Cameron called for “a campaign against criminalisation”. However advocacy on this vitally important issue is in its infancy, hampered by lack of information on a local, national and international level.

Description: A global overview of prosecutions to December 2009, based on data from GNP+ Global Criminalisation Scan (http://criminalisation.gnpplus.net); media reports collated on criminalhivtransmission.blogspot.com and WHO Europe pilot human rights audit. Top 20 ranking is based on the ratio of rate per year/per HIV population.

Lessons learned: Prosecutions for non-intentional HIV exposure and transmission continue unabated. More than 60 countries have prosecuted HIV exposure or transmission and/or have HIV-specific laws that allow for prosecutions. At least eight countries enacted new HIV-specific laws in 2008/9; new laws are proposed in 15 countries or jurisdictions; 23 countries actively prosecuted PLHIV in 2008/9.

Next steps: PLHIV networks and civil society, in partnership with public sector, donor, multilateral and UN agencies, must invest in understanding the drivers and impact of criminalisation, and work pragmatically with criminal justice system/lawmakers to reduce its harm.

Video produced by www.georgetownmedia.de

|

| This table reflects amended data for Sweden provided by Andreas Berglöf of HIV Sweden after the conference, relegating Sweden from 3rd to 4th. Its laws, including the forced disclosure of HIV-positive status, remain some of the most draconian in the world. Click here to download pdf. |

Edwin J Bernard: Where HIV Is a Crime, Not Just a Virus (AIDS 2010)

Edwin J Bernard presents a global overview of laws and prosecutions at the XVIII International AIDS Conference, Vienna, 22 July 2010.

Abstract: Where HIV is a crime, not just a virus: a global ranking of prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

Issues: The global (mis)use of the criminal law to control and punish the behaviour of PLHIV was highlighted at AIDS 2008, where Justice Edwin Cameron called for “a campaign against criminalisation”. However advocacy on this vitally important issue is in its infancy, hampered by lack of information on a local, national and international level.

Description: A global overview of prosecutions to December 2009, based on data from GNP+ Global Criminalisation Scan (criminalisation.gnpplus.net); media reports collated on criminalhivtransmission.blogspot.com and WHO Europe pilot human rights audit. Top 20 ranking is based on the ratio of rate per year/per HIV population.

Lessons learned: Prosecutions for non-intentional HIV exposure and transmission continue unabated. More than 60 countries have prosecuted HIV exposure or transmission and/or have HIV-specific laws that allow for prosecutions. At least eight countries enacted new HIV-specific laws in 2008/9; new laws are proposed in 15 countries or jurisdictions; 23 countries actively prosecuted PLHIV in 2008/9.

Next steps: PLHIV networks and civil society, in partnership with public sector, donor, multilateral and UN agencies, must invest in understanding the drivers and impact of criminalisation, and work pragmatically with criminal justice system/lawmakers to reduce its harm.

Video produced by georgetownmedia.de

Global: UN Global Commission on HIV and the Law launched, US refuses entry to TAG member

Yesterday, UNDP and UNAIDS launched the new Global Commission on HIV and the Law, previously mentioned here.

The Commission’s aim is to increase understanding of the impact of the legal environment on national HIV responses. Its aim is to focus on how laws and law enforcement can support, rather than block, effective HIV responses.

Although most reports have simply reworked parts of the UNDP or UNAIDS press releases, there is a lot more detail available from the UNDP website, including links to the five page information note and detailed biographies of the Commissioners and members of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG).

The Global Commission on HIV and the Law brings together world-renowned public leaders from many walks of life and regions. Experts on law, public health, human rights, and HIV will support the Commissions’ work. Commissioners will gather and share evidence about the extent of the impact of law and law enforcement on the lives of people living with HIV and those most vulnerable to HIV. They will make recommendations on how the law can better support universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support. Regional hearings, a key innovation, will provide a space in which those most directly affected by HIV-related laws can share their experiences with policy makers. This direct interaction is critical. It has long been recognized that the law is a critical part of any HIV response, whether it be formal or traditional law, law enforcement or access to justice. All of these can help determine whether people living with or affected by HIV can access services, protect themselves from HIV, and live fulfilling lives grounded in human dignity.

The list of Commissioners is extremely impressive and includes two former presidents – Fernando Henrique Cardoso, former President of Brazil and Festus Gontebanye Mogae, former President of Botswana – and several currently elected politicans – US Congresswoman Barbara Lee, New Zealand Representative Charles Chauvel and Hon. Dame Carol Kidu, MP in Papua New Guinea. It also includes the two most respected judges in the field of HIV and the law – Australia’s Hon. Michael Kirby and South Africa’s Justice Edwin Cameron.

I’m also proud to note that many members of the TAG are friends and colleagues including Aziza Ahmed, Scott Burris, Mandeep Dhaliwal, Richard Elliott, Kevin Moody, Susan Timberlake, and Matthew Weait.

Last week (17-18 June), the TAG held its first meeting at the UNDP building in New York. I hear it was amazingly interesting and productive. However, one member of the TAG, Cheryl Overs, was missing. This tireless and passionate advocate on behalf of sex workers, who is currently Senior Research Fellow in the Michael Kirby Centre for Public Health and Human Rights at Monash University, was apparently denied entry by US immigration because she deemed a security risk due to her association with sex work. Oh, the irony!

The Commission’s findings and recommendations will be announced in December 2011, in time for AIDS 2012 due to be held in Washington DC.