Abstract

Ekubu, Y. (2016) Reducing Vulnerabilities to HIV: Does the Criminalization of HIVAIDS Patients Contribute?. Beijing Law Review, 7, 292-313. doi: 10.4236/blr.2016.74027.

Abstract

Ekubu, Y. (2016) Reducing Vulnerabilities to HIV: Does the Criminalization of HIVAIDS Patients Contribute?. Beijing Law Review, 7, 292-313. doi: 10.4236/blr.2016.74027.

LOS ANGELES — In California, outdated HIV criminalization laws do not reflect the highly effective medical advances for reducing the risk of HIV transmission and extending the quantity and quality of life for people living with HIV.

HIV criminalization is a term used to describe laws that either criminalize otherwise legal conduct or that increase the penalties for illegal conduct based upon a person’s HIV-positive status. California has four HIV-specific criminal laws.

In HIV Criminalization in California: Evaluation of Transmission Risk, researchers Amira Hasenbush and Dr. Brian Zanoni suggest that these HIV criminal laws in California are not in line with medical science and technology related to HIV and may, in fact, work against best public health practices.

“Nine out of ten convictions under an HIV-specific criminal law or sentence enhancement have no proof of exposure to HIV, let alone transmission,” said Amira Hasenbush. “No HIV criminal laws in California require transmission for a conviction.”Key findings include:

HIV criminal laws have been disproportionately applied to sex workers. This has a disproportionate impact on women and people of color. Since solicitation by definition includes survival and subsistence sex work, these laws are also likely to disproportionately impact LGBT youth and transgender women of color.

Laws that criminalize conduct of a person who knows that they are HIV-positive may disincentivize testing and work against best public health practices.

The Williams Institute, a think tank on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, is dedicated to conducting rigorous, independent research with real-world relevance.

Full report can be read here

Media accused of racism in reporting HIV-related crime

Black males with HIV account for 20 per cent of the 181 people charged for no disclosing HIV status to sexual partners, but 62 per cent of newspaper articles focused on their cases.

Canadian mainstream media disproportionally focus on black immigrant men criminally charged for not disclosing HIV status to their sexual partners when the majority of offenders are white, says a new study.

To mark World AIDS Day on Wednesday, a team of Canadian researchers released the pioneering study last week identifying “a clear pattern of racism” toward black men in the reporting of HIV non-disclosure in Canadian newspapers.

“The most striking revelation of this report was the grand scale of stereotyping and stigmatizing by Canadian media outlets in their sensationalistic coverage of HIV non-disclosure cases,” said Eric Mykhalovskiy, a York University sociology professor, who leads the team.

“It’s upsetting to read myths masquerading as news and repeating the theme of how black men living with HIV are hypersexual dangerous ‘others.’ This approach not only demeans journalism, but it inflames racism and HIV stigmatization, undermining educational and treatment efforts.”

Based on the database of Factiva, an English-language Canadian newspaper articles from 1989 to 2015, researchers from York, University of Toronto and Lakehead University identified 1,680 reports of HIV non-disclosure cases. Of those reports 68 per cent, or 1,141 of the articles, focused on racialized defendants.

According to court records of HIV-related criminal cases in Canada, African, Caribbean and black men living with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, account for 20 per cent or 36 of the 181 people charged for these offenses. However, 62 per cent or 1,049 of the 1,680 media reports focused on these 20 per cent of the cases.

Immigrants and refugees receive particularly higher amount of coverage. While only 32 of the 181 accused are known to be migrants to Canada, yet stories about their offences represented 62 per cent (1,046 of 1,680) of the media coverage.

“The report documents the media’s stigmatizing and unjust racial profiling of black heterosexual immigrant men in HIV non-disclosure cases that perpetuates systematic discrimination,” said Christian Hui, an HIV activist and co-founder of the Canadian Positive People Network.

“We know next to nothing about them other than their name, age, residence, occupation, the charges they face,” said the report. “What is distinct about the coverage of African, Caribbean and black male defendants is how (they) are linked with racializing forms of representation in ways that amplify connections between HIV, criminality, race and ‘foreignness.’”

Mykhalovskiy said the research team recognized that accused criminals often refuse to speak with the media at their counsel’s advice, but it does not change the fact black immigrant offenders are disproportionally represented in the coverage.

The study urges the Canadian media to treat HIV non-disclosure as a health issue and not simply a crime story; to stop using mug shots that further stigmatizing and discriminate people with HIV as criminals; and to reach out to AIDS service organizations when interviewing sources for these stories.

Published in The Star, on Dec 1, 2016

Abstract:

September 29, 2016

The fight to combat HIV criminalization is not new. After years of activism, gains are finally being made to repeal statutes that turn a person’s knowledge of their HIV status into a crime.

Just this year, Colorado’s HIV modernization bill comprehensively repealed almost all of the HIV-specific statutes in the state. This is an evidence-based success: Criminalizing people’s HIV status does not inhibit HIV transmission, but instead turns their knowledge and treatment of that status into evidence of a crime. This weaponizes their knowledge and their enrollment in the very care public health officials recommend, forcing people to weigh testing and treatment against fear of arrest.

With the growing success in fighting HIV criminalization, it is now time for advocates to take the conversation beyond the repeal of HIV-specific statutes and to confront the larger context of how criminalization encourages HIV transmission.

The growing data on where and when laws criminalizing a person’s status are implemented show that the people in the crosshairs of these laws are often those already criminalized through their engagement in sex work. The ostensible targets of HIV criminalization laws may be people who are not otherwise criminalized, but the data clearly show who faces most of their impact. The more common way that people who are HIV positive are criminalized for their status is not through general HIV criminalization statutes, but through laws that upgrade a misdemeanor prostitution charge to a felony if a sex worker is HIV positive.

The Williams Institute looked at who is charged and convicted of HIV-specific statutes in California found that “[t]he vast majority (95%) of all HIV-specific criminal incidents impacted people engaged in sex work or individuals suspected of engaging in sex work.” Research out of Nashville, Tennessee, corroborated this picture, with charges disproportionately targeting people arrested for prostitution, who then faced a felony upgrade and (until last year) were required to register as sex offenders for being HIV positive. However, these laws are not the only way criminalization increases sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV transmission, and advocacy must expand its vision to include the fuller context.

At the Sex Workers Project, we work with individuals who trade sex across the spectrum of choice, circumstance and coercion. For sex workers, the relationship between criminalization and health is complex and deeply interwoven.

When we look at the role of HIV transmission in the lives of our clients and community, it is not simply HIV-specific statutes, but the tactics of policing and the instability created through criminalization that increase people’s vulnerability. If the long-term goal is to end the spread of HIV, advocacy should target criminalization more holistically and see HIV modernization, or the on-going state-by-state push to repeal these statutes, as just one of the initial steps needed to explore the nexus between public health and criminalization.

When we expand our scope beyond these specific statutes to look at how policing and criminalization encourage HIV transmission, a more complex and multi-layered picture emerges. For instance, the relationship between evidence of a crime and transmission of HIV does not end with simply knowing one’s status. Law enforcement’s use of condoms as evidence of prostitution has a chilling effect. In research on the impact of policing that uses safer-sex supplies as evidence of a crime, many sex workers reported that they were afraid to carry condoms or take condoms from outreach workers, regardless of whether they were engaging in prostitution at that time. Most impacted by these policing practices were transgender women of color, a population acknowledged to be already at higher risk for HIV transmission. Transgender women are commonly profiled as being engaged in sex work, and therefore, were most at risk for being arrested for the mere possession of condoms. This means that policing practices are actively putting the community with the highest vulnerability to HIV at even higher risk of transmission.

Further, policing procedures that inundate areas “known for prostitution” with law enforcement push sex workers into isolated locations to avoid arrest. This means isolation from peers who can provide harm reduction and safety, and from outreach workers who may offer resources — in addition to making sex workers vulnerable to physical and sexual assault, as physical isolation carries its own risk of HIV transmission.

The fight for HIV modernization bills across the country is already having a demonstrable success. The recent Colorado HIV modernization bill shows what a comprehensive policy can look like. Many other state-based efforts have made sure their work encompasses those most impacted by HIV-specific statutes and fought to include in their advocacy sex workers and organizations serving people who trade sex.

But these policy changes should not be where the momentum ends. HIV criminalization is only one part of the larger on-going dialogue on the nexus between criminalization and public health that deeply impacts the lives of marginalized communities. When more people understand how criminalization affects individual and public health, we can expand the impact of our work to address these larger issues and shift our goals to not just avoiding the criminalization of HIV, but also stemming its spread.

Kate D’Adamo is the national policy advocate at the Sex Workers Project at the Urban Justice Center, focusing on laws, policies and advocacy that target folks who trade sex, including the criminalization of sex work, anti-trafficking policies and HIV-specific laws. Previously, Kate was a community organizer and advocate for people in the sex trade with the Sex Workers Outreach Project-NYC and Sex Workers Action New York. She holds a BA in political Science from California Polytechnic State University and an MA in international affairs from the New School University.

Originally published in The Body on 29/09/2016

Paidamoyo Chipunza: Senior Health Reporter

On November 19, 2014, then Chinhoyi regional magistrate Mr Never Katiyo sentenced 39-year-old Nyengedzai Bheka to 15 years in prison for willfully transmitting HIV to a 17-year old pupil. In his ruling, Mr Katiyo said infection of that nature was tantamount to a death penalty on the girl since she was an immature minor. “This is a very rare case that we have had to deal with as the courts and we have to set a precedent that is deterrent to would-be offenders,” said Mr Katiyo.“Although it was a matter involving a single witness the court is convinced that there was deliberate infection.” Bheka’s case serves as both a template for discussion on aptness of wilful transmission of HIV as a law and as precedence to the 1,4 million Zimbabweans estimated to be living with HIV who by virtue of them being HIV positive are ‘‘potential criminals’’.

Elizabeth Tailor Human Rights Award winner and HIV activist, Ms Martha Tholanah said this law must be scrapped because it stigmatised and discriminated against people living with HIV. Ms Tholanah, who has been living with HIV for the past 14 years, said criminalisation of wilful HIV transmission was done a long time ago on the advent of the disease, when no one wanted to be associated with it. She, however, said owing to developments in the medical field, HIV is now just like any other disease hence the law must be informed by science trends. “Evidence has shown that chances of transmitting HIV to another person if you are on treatment are slim. The law must then speak the same language with science to achieve our national and global goals and targets,” said Ms Tholanah. She said the current law discouraged people from getting tested thereby delaying them from accessing treatment early, reversing global efforts to end Aids by 2030.

To end Aids by 2030, Zimbabwe adopted the United Nations goals popularly referred to as the 90-90-90 targets. These targets entail that at least 90 percent of people living with HIV must be tested by the year 2020. For those diagnosed with HIV, at least 90 percent of them must be on antiretroviral treatment and a further 90 percent of those on treatment must have their viral load fully suppressed by the year 2020.

“How do you get tested when you know that you risk being a criminal?” said Ms Tholanah. She said while science has proved that taking antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) actually reduced the risk of one transmitting HIV to another person, the law drew conclusions on deliberate HIV transmission from the fact that one was on ARVs — a direct contradiction of science.

Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights HIV and Law Unit project manager Mr Tinashe Mundawarara said HIV involved science and it was therefore difficult to ascertain the direction of infection even in developed countries where there is sophisticated equipment.

“It is still difficult to point out the direction of infection and also people might have acquired the same HIV genotype from a common source, which might also dismiss infection from the concerned partners,” said Mr Mundawarara.

Section 79 (1) of the Criminal Codification and Reform Act on deliberate transmission of HIV reads: “Any person who knowingly that he or she is infected with HIV, or realising that there is a real risk or possibility that he or she is infected with HIV, intentionally does anything or permits the doing of anything which he or she realises involves a real risk or possibility of infecting another person with HIV, shall be guilty of deliberate transmission of HIV, whether or not he or she is married to that other person and shall be liable to imprisonment for a period not exceeding twenty years.“It shall be a defence to a charge under subsection (1) for the accused to prove that the other person concerned knew that the accused was infected with HIV and consented to the act in question, appreciating the nature of HIV and the possibility of becoming infected with it.”

Mr Mundawarara said this law was too broad and that the accompanying defence on informing the other person and ‘‘appreciating the nature of HIV’’ was also vague making it difficult to prosecute and convict someone of committing a crime. He said the law itself was not clear on what understanding the nature of HIV meant.

“Does it mean the scientific or genetic make-up of the HIV virus or does it mean how HIV impacts on the immune system,” he said. Mr Mundawarara said the law also criminalised sex by people living with HIV and Aids, hence it infringed on their rights and promoted stigma and discrimination around HIV. “One can still be charged even if transmission has not occurred because it says ‘ . . . real risk or possibility of infecting another person with HIV’. So, if you engage in unprotected sex which involves a real risk of transmitting HIV to another person, you risk being charged, thus making everyone living with HIV a potential criminal,” said Mr Mundawarara.

Mr Mundawarara said this legislation should therefore be scrapped as it reversed public health gains in national HIV and Aids response.He said the law can still punish people who willfully transmit HIV through other provisions such aggravated indecent assault.

Katswe Sisterhood director Ms Talet Jumo said the law was unfair on women who in most cases knew of their status first through antenatal care or voluntary testing, hence risked being charged of having infected their spouses. “Sometimes women may delay to inform their partners of their status due to fear of gender based violence and using that law, their partners may still drag them to the courts for deliberately transmitting HIV,” said Ms Jumo.

National Aids Council board chairman Mr Everisto Marowa said in line with the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets, Zimbabwe must reduce new HIV infections from the current 64 000 a year to about 6 000 — a figure he described as a huge considering that HIV was preventable.He said NAC was aiming to have less than 1000 new infections by the year 2020.“NAC is geared for the task ahead and ready to provide the needed leadership with guidance from Government,” said Dr Marowa.

HIV remains a major public health threat in Zimbabwe with a prevalence rate of about 15 percent.

Canada’s laws governing HIV disclosure are dangerously out of date. Anyone who tests positive and doesn’t warn their lover can be charged with aggravated sexual assault, carrying a penalty up to life in prison and lifelong registry as a sex offender. Fearing the potential criminal consequences of knowing, some people at risk won’t get tested.

Anyone, naturally, would hope an intimate partner would reveal if he or she was HIV-positive. But the criminal law is a blunt instrument with which to enforce honesty in a relationship. It sends a dangerous message people can assume their sexual partners are HIV-negative unless they reveal otherwise. And it further marginalizes a group already beset by stigma and discrimination.

People with HIV have many reasons for keeping the diagnosis to themselves. They may reasonably fear rejection, damaging public exposure or violence. But sex without disclosure, under the law, is rape; the omission invalidates consent.

Perhaps that made sense in the epidemic’s early days, when the risk was equated with death. But medical advances have changed the landscape.

Sex with HIV is no longer tantamount to Russian roulette. For this we can thank condoms and antiretroviral therapy (ART), which can bring a person’s viral load to undetectable levels. Either one of these measures reduces the risk of transmission to “negligible.” That’s not my opinion — it’s the scientific consensus of 70 leading HIV physicians and medical researchers across Canada.

In cases where there is virtually no risk of transmitting the virus, it’s hardly logical to prosecute non-disclosure. A 2012 Supreme Court ruling has already clarified disclosure is not required in cases where the risk of transmission is extremely low — specifically, when the viral load is undetectable and condoms are used.

Legislators should heed the scientists.

Their verdict is clear: The data supports decriminalizing non-disclosure if just one of these measures — effective ART or condom use — is in place to protect one’s partner. The consensus paper was published in 2014 to remedy the poor understanding of HIV transmission among prosecutors and judges. The authors expressed an ethical duty not only in the interest of justice, but also “to remove unnecessary barriers to evidence-based HIV prevention strategies.” Two years later, we’re still not listening.

Canada is a world leader in HIV criminalization, according to the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. At least 180 people have been prosecuted for non-disclosure. Half of these were in Ontario, with at least three new charges just this summer.

The double standard is no longer appropriate. ARTs have transformed HIV from a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition. Yet there are no criminal penalties for failing to notify a partner of an array of STDs, some of which can lead to infertility or cancer. Instead, quite logically, we promote self-protection through safer sex.

People withhold information about their sexual histories. One hardly expects a full accounting of partners, past STD treatments or other details one might be inclined to omit in the blush of a budding romance. The point is, people can’t assume their partner has told them everything — nor knows everything there is to tell.

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, one in four people with HIV don’t know they are infected. If knowledge of the virus can turn sex into a criminal act, it creates a significant disincentive to seek testing and treatment. That’s a public health disaster.

Put simply: Treatment reduces transmission. If it’s good public policy to encourage HIV testing, then it’s good public policy to make it safe to know the results.

Published in the Melfort Journal on 23/09/2016

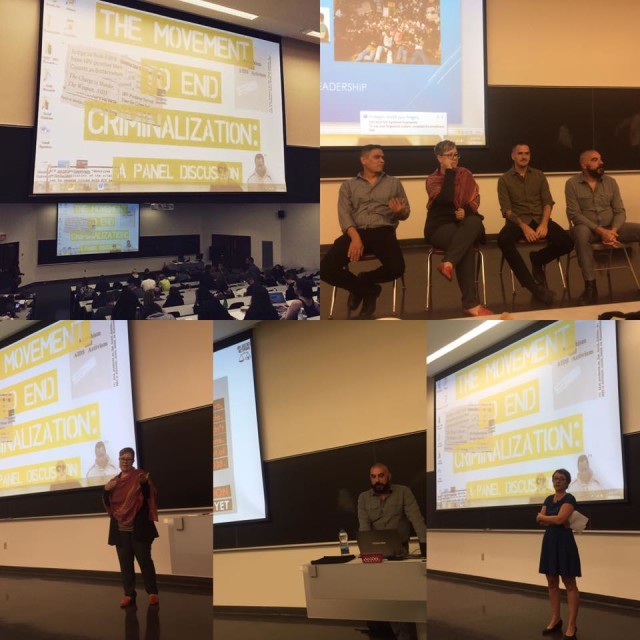

Last week, Concordia Unversity in Montreal, Canada, held the world premiere public screening of HJN’s ‘HIV is not a crime training academy’ documentary, followed by three powerful and richly evocative presentations by activist and PhD candidate, Alex McClelland; HJN’s Research Fellow in HIV, Gender, and Justice, Laurel Sprague; and activist and Hofstra University Professor, Andrew Spieldenner.

The meeting, introduced by Liz Lacharpagne of COCQ-SIDA and by Martin French of Concordia University – who put the lecture series together – was extremely well-attended, and resulted in a well-written and researched article by student jounrnalist, Ocean DeRouchie, alongside a strong editorial from Concordia’s newspaper, The Link.

(The full text of both article and editorial are below.)

Presentations included:

Articles based on a number of these important presentations will be published on the HJN website in coming

weeks.

The Movement to End HIV Criminalization

Decrying Criminalization

Concordia Lecture Series Prompts Discussion on HIV Non-disclosure

The sentiment surrounding HIV/AIDS is often one of discomfort. But the reluctance to speak openly about such a significant and impactful disease is hurting the people closest to it.

Under current Canadian legislation, HIV non-disclosure is criminalized. It exercises some of the most punitive aspects of our criminal justice system, explained Alexander McClelland, a writer and researcher currently working on a PhD at Concordia.

McClelland was one of four panelists speaking under Concordia’s Community Lecture Series on HIV/AIDS on Thursday, Sept. 15 in the Hall building. The collective puts on multiple panel-based events in order to address the attitudes, laws, and intersections of political and socioeconomic stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS.

Talking About HIV, Legally

There are three distinct charges that guide prosecutors in HIV cases—transmission (giving the disease to someone without having disclosed your status), exposure (e.g. spitting or biting) and non-disclosure (not informing a sexual partner about your HIV/AIDS status).

Aggravated sexual assault and attempted murder are some of the charges that defendants often face, explained Edwin Bernard, Global Coordinator for the HIV Justice Network, during the discussion.

While there are clearly defined situations in which you are legally obligated to tell a sex partner about your HIV status, there are no HIV-specific laws. This results in the application of general law in cases that are anything but general.

In 2012, the Supreme Court of Canada established that “people living with HIV must disclose their status before having sex that poses a ‘realistic possibility of HIV transmission.’”

Aidslaw.ca presents a clear map of situations in which you’d have to tell a sex partner about your status because, in fact, it is not in all scenarios that you’d be legally required to have the discussion.

A lot of it depends on your viral load—the amount of measurable virus in your bloodstream, usually taken in milliliters. A “low” to undetectable viral load is the goal, and is achieved with anti-viral medication.

Treatment serves to render HIV-positive individuals non-infectious, and therefore lowering the risk of transmission. A “high” viral load indicates increased amounts of HIV in the blood.

If protection is used and with a low viral load, one might not have to disclose their status at all.

That said, there is a legal obligation to disclose one’s HIV-positive status before any penetrative sex sans-condom, regardless of viral load. You’d also have to bring it up before having any sex with protection if you have a viral load higher than “low.”

But not all sex is spelled out so clearly.

Oral sex, for instance, is a grey area. Aidslaw.ca says, “oral sex is usually considered very low risk for HIV transmission.” They write that “despite some developments at lower level courts,” they cannot say for sure what does not require disclosure.

There are “no risk” activities. Smooching and touching one another are intimate activities that, as health professionals say, pose such a small risk of transmission that there “should be no legal duty to disclose an HIV-positive status.”

Moving Up, and Out of Hand

Court proceedings are based on how the jury and judge want to apply general laws to specific instances. There are a lot of factors that can influence the outcome.

The case-to-case outlook leads to the criminal justice system dealing with non-disclosure in such a disproportionate way, said McClelland.

The situation begs the question: “Why is society responding in such a punitive way?” asked McClelland.

This isn’t to say that not disclosing one’s HIV status “doesn’t require some potential form of intervention,” he explained, adding that intervention could incorporate counseling, mental-health support, encouragement around building self-esteem and learning how to deal and live with the virus in the world. “But in engaging with the very blunt instrument that is the criminal law is the wrong approach.”

He continued to explain that the reality of the criminalization of HIV ultimately doesn’t do anything to prevent HIV transmission.

“It’s just ruining people’s lives,” said McClelland, who has been interviewing Canadians who have been affected by criminal charges due to HIV-related situations. “It’s a very complex social situation that requires a nuanced approach to support people.”

“It’s just ruining people’s lives. It’s a very complex social situation that requires a nuanced approach to support people.” – Alexander McClelland, Concordia PhD student

Counting the Cases

The Community AIDS Treatment Information Exchange, a Canadian resource for information on HIV/AIDS, states that about 75,500 Canadians were living with the virus by the end of the 2014, according to the yearly national HIV estimates.

That number has gone up since. On Monday, Sept. 19, Saskatoon doctors called for a public health state of emergency due to overwhelmingly increasing cases of new infections and transmission, according to CBC.

In Quebec, there have been cases surrounding transmission and exposure. In 2013, Jacqueline Jacko, an HIV-positive woman, was sentenced to ten months in prison for spitting on a police officer—despite findings that confirm that the disease cannot be transmitted through saliva.

In this situation, Jacko had called for police assistance in removing an unwelcome person from her home. Aggression transpired between her and the officers, resulting in her arrest and eventually her spitting on them, according to Le Devoir.

“[This case] is so clearly based on AIDS-phobia, AIDS stigma and fear,” added McClelland, “and an example of how the police treat these situations and use HIV as a way to criminalize people.”

Police intervention is crucial in the fight against HIV criminalization. McClelland urged people to consider the consequences of involving the justice system in these kinds of situations.

“It’s important to understand that the current scientific reality for HIV is that it’s a chronic, manageable condition. When people take [antivirals] they are rendered non-infectious,” he said. “They should then understand that the fear is grounded in a kind of stigma and historical understanding of HIV that is no longer correct today.”

The first instinct, or notion of calling the police in an instance where one feels they may have been exposed to the virus in some way is “mostly grounded in fear and panic,” he said.

“[Police] respond in a really disproportionate, violent way towards people—so I would consider questioning, or at least thinking twice before calling the police,” McClelland explained.

On the other hand, he suggested approaching the situation in more conventional, educational and progressive methods.

“I think it could be talked through in different ways—by going to a counselor, talking to a close friend, engaging with a community organization, learning about HIV and what it means to have HIV, and understanding that the risk of HIV transmission are very low because of people being on [antivirals].”

As for the current state of Canadian legislation, there are a lot of complexities that hinder heavy-hitting changes to the laws.

Due to the Supreme Court’s rulings in 2012, they are unlikely to review the decision for another decade. For now, the main course of action is “on the ground,” said McClelland. From mitigating people from requesting police involvement in order to “slow down the cases,” to raising awareness through events such as Concordia’s Community Lecture Series, and engaging with the people to resolve issues in community-based ways and collective of care.

Then, McClelland said, “trying to do high-level political advocacy to get leaders to think about how they can change the current situation” would be the next step.

Editorial: Community-Based Research is the Key to HIV Destigmatization and Decriminalization

Receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis is already a life sentence. The state of Canada’s legal system threatens to give those living with the virus another one.

An HIV diagnosis is accompanied by its own set of complexities that are not encompassed in Canada’s criminal law. By pushing HIV non-disclosure cases into the same box as more easily defined assault cases, we are generalizing an issue that frankly cannot be simplified.

This does not reflect the reality that one faces when living with HIV. Criminalizing the virus further stigmatizes what should and could be everyday activities.

This puts the estimated 75,000 Canadians living with HIV at risk of being further isolated. This takes us backwards, considering the scientific progress that has been made to make living with the virus manageable. Under the proper antiviral medication, one’s risk of transmitting the disease is incredibly low. This stigma is rooted in an antiquated understanding of what HIV is and the associated risks—much of that fear having emerged primarily as a result of homophobia.

Further, with over 185 cases having been brought to court, Canada is leading in terms of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure. This pushes marginalized communities farther away. According to estimates from 2014, indigenous populations have a 2.7 higher incidence rate than the non-indigenous Canadian average. Gay men have an incidence rate that is 131 times higher than the rest of the male population in Canada.

As of Sept. 19, doctors in Saskatchewan are calling on the provincial government to declare a public health state of emergency, with a spike in HIV/AIDS cases around the province.

In 2010, it’s reported that indigenous people accounted for 73 per cent of all new cases in the province. Outreach and treatment for these communities are at the forefront of Saskatchewan’s doctor’s recommendations for the government.

With such a highly treatable virus, however, the problem should never have gone this far. It is an excerpt from a much bigger issue.

As we can see from the available statistics, HIV—both the virus and its criminalization—is a mirror for broader inequalities that exist within society. HIV related issues disproportionately affect racialized people, gender non-conforming people, and other marginalized groups.

Discussions around HIV also must include discussions around drug use. The heavy criminalization of injection drugs has created a context where users are driven deep underground, thus putting them at an incredibly high risk for contracting the virus. Treating drug use as a health rather than a criminal issue is an integral part of any effective HIV prevention strategy. Safe injection sites, such as Vancouver’s InSite, have made staggering differences in their communities and prove to be a positive way of combating the spread of HIV.

This is just one of the many ways that we can control the spread of HIV without judicial intervention, without turning the HIV-positive population into criminals.

Using community-based research enables us to not only understand the needs of the affected population—particularly when it comes to understanding the almost inherent intersectionality associated with the spread of HIV—but also allows us to better target our resources towards those who need it most.

Often times, that stretches to include those closest to HIV-positive individuals. Spreading awareness, and developing resources and a support network for them is just as important in fighting the stigmatization of the virus.

The Link stands for the immediate decriminalization of HIV non-disclosure, and the move towards restorative justice systems in non-disclosure cases. As always, those directly affected by an issue are the ones with who are best positioned to create a solution—something that the restorative justice framework embraces.

The disclosure of one’s HIV status is important. Jailing those who don’t disclose it, however, won’t make the virus go away. It simply isolates the problem, places it out of site and out of mind.

Criminalizing HIV patients is less about justice than it is about appeasing the baseless fears of the general population. It’s time for a more effective solution.

Friday and Saturday, Montreal will play host to the Fifth Replenishment Conference of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. While much of the discussion will be focused on developing countries (the Global South), where the fund has played a crucial role since is creation in 2002, this is also an appropriate time to take stock of Canadian realities.

At a time when the global effort is suffering from precarious funding, Canada has stepped up to the plate by increasing its contribution by 20 per cent, to a total of $785 million over the next three years. This commitment is to be applauded. It proves that there is a willingness on the part of government to make Canada a leader once again on the international scene. It is also a promising reminder that increased donations will get us closer to beating these diseases once and for all.

But good leadership also puts the spotlight on Canada’s own responsibility to address human-rights issues that are impediments to the improvement of public health and fair access to health services.

In the HIV sector, we know that gender inequality, racism and homophobia are the breeding grounds for the epidemic. Poverty and discrimination are further barriers to access and care. As was recently pointed out by Canada’s Minister of International Development and La Francophonie, Marie-Claude Bibeau, HIV has a particularly heavy impact on young women.

In order to continue to play its part as an international leader, Canada has to make good on commitments to end these epidemics here at home. We have work to do in our own backyard in order to align the fight against HIV/AIDS with human-rights advocacy.

Canada in 2016 is a country that still imposes criminal penalties on people living with HIV: they still risk prison sentences for having sexual relations without disclosing their HIV status to their partners when they have taken the necessary precautions to avoid transmission (use of a condom or undetectable viral load), and when there has been no transmission. This increases stigma, goes against science and UNAIDS recommendations, and should not be the case in a country that otherwise is helping lead the way.

Leadership comes from inspiring the best public policy, especially when it is supported by scientific data. In this regard, Canada must go farther and support the opening of supervised-injection sites. Such harm-reduction approaches are proven to reduce rates of infection.

Furthermore, we must work to create social and legal frameworks that help sex workers, as recommended by such NGOs as Amnesty International. It is crucial that we repeal Bill C-36, the so-called “Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act” that criminalizes sex work in Canada.

This major international event will also be an opportunity to highlight how these epidemics affect migrants. Mandatory testing by immigration authorities contradicts recommendations by Canadian health experts. Rejecting migrants on the basis of their HIV or health status continues to foster prejudice in this regard. Economic arguments for refusing them entry only serve to exacerbate such inequalities. It is high time to look at universal access to treatment and the real cost of its being denied to certain people.

The Global Fund Replenishment Conference is a fitting time to demonstrate Canada’s financial support for countries most affected by HIV, TB, and malaria. Canada’s commitment to international aid is a solid foundation for global action on these issues.

But now is also the time for us to lead by example in our own country. There is much work to be done before we can truly “End it. For Good.” We need concrete measures that show Canadians stand with and support HIV-positive people.

Gabriel Girard is a post-doctoral researcher in sociology at Université de Montréal. Pierre-Henri Minot is executive director of Portail VIH/sida du Québec in Montreal. This article is based on an open letter that has been co-signed by more than 150 others. The full list is available at pvsq.org/globalfunds2016.

You can select your preferred language from the 'Select Language' menu at the top of the page.