Overview

Missouri law criminalises perceived ‘exposure’ to HIV through both general communicable disease laws and an HIV-specific law applying to sex workers. The first laws were initially enacted in 1988 and were amended several times, most recently in 2021 when the scope of the laws was narrowed.

Missouri maintains an ‘exposure’ provision under state health law. When originally enacted in 1988, the law was HIV-specific and criminalised donations of blood, organs, sperm, or tissue, and ‘exposure’ by contact which created a ‘grave and unjustified risk’ of transmission, but amendments in 1997 reformulated the law to require ‘reckless exposure’ of another without their knowledge or consent through contact with blood, semen, or vaginal fluid during sex (including oral) or by sharing of needles. An explicit exclusion of condom use as a defence was added. Then in 2002, the law was expanded to include biting and ‘exposure’ to mucous membranes or wounded skin, and increased penalties to up to 15 years’ imprisonment (previously seven), or up to 30 years’ where transmission occurred. This law remained unchanged until 2021. Throughout this time criminalisation was possible without any proof of intent, a risk of transmission, or actual transmission.

The 2002 reform also extended the state’s general ‘prostitution’ crime to include enhanced penalties for those who commit the offence while knowingly living with HIV. The law prohibits engaging in, offering, or agreeing to engage in sexual conduct with another in exchange for ‘something of value’. Elsewhere in the statute, ‘sexual conduct’ is defined to include acts which carry little to no risk of transmission, including oral sex, penetration by fingers or objects, and touching of genitals, anus, or breasts for sexual gratification. Condom use is explicitly stated to be no defence. The general offence is punishable by six months’ imprisonment, while the HIV-specific offence is enhanced to five to 15 years’ imprisonment.

In 2005 and 2010, Missouri added additional ‘exposure’ offences concerning people in correctional or mental health facilities who are ‘exposed’ to blood, semen, urine, faeces, or saliva. There is both a base offence which applies to anyone and carries a penalty of up to four years’ imprisonment, and an enhanced offence which applies to anyone knowingly living with HIV or hepatitis who ‘exposes’ an officer in a way ‘scientifically shown’ to be a means of transmission, which carries a penalty of up to seven years’ imprisonment.

A 2020 analysis by the Williams Institute found that Missouri had one of the highest rates of enforcement of HIV laws among US states. It found that between 1990 and 2019, 209 people were arrested for 263 incidents under HIV-specific laws, 107 of which resulted in conviction. The majority (91%) were charged under the general ‘exposure’ offence, and almost a quarter of these were charged with actually causing transmission. A small number of offences appear to involve blood donations, and 6.5% of incidents related to sex work while HIV-positive, but only three people have ever been convicted of this offence. In addition to these HIV offences, 52 prosecutions were found under the ‘exposure’ to HIV/hepatitis in a security facility law, but as this data is not disaggregated by disease it is not possible to know how many involved HIV.

These data paint an unusual picture of enforcement in Missouri as compared to other states. Firstly, there are several blood donation offences recorded, whereas these laws seem rarely if ever used in other states – however the analysis suggests this may be attributable to a miscoding of incidents. Secondly, there are few sex work offences, which make up the bulk of prosecutions in many other states, such as California and Florida. As with many jurisdictions, the laws disproportionately affected Black people, particularly Black men.

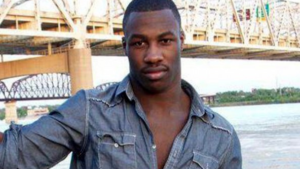

Prior to reform, the law did not require any proven risk of transmission, resulting in arrests for acts which carry virtually no risk of transmission, such as spitting and biting. However, the case which perhaps did most to coalesce opposition to the law in Missouri was that of Michael Johnson, a 21-year-old college student who was charged in 2013 under the ‘exposure’ law for allegedly having sex with several partners without disclosing his status. In 2015 he was found guilty and sentenced to 30.5 years’ imprisonment. The severity of this sentence garnered significant backlash from HIV, gay, and Black advocates. The conviction was overturned in 2016 and a new trial ordered, but before that trial could take place, Johnson accepted a plea deal and was released in 2019.

This case has been credited with galvanising the anti-HIV criminalisation movement in Missouri. The MO HIV Justice Coalition was established to lead advocacy efforts to modernise the state’s HIV criminal laws. Previous efforts to challenge the laws via the courts – though constitutional challenges in 1998 and 2016 – were both rejected by the Supreme Court. In early 2020 the first ‘modernisation’ proposals reached the legislature when a bipartisan group of lawmakers, supported by the MO HIV Justice Coalition and others, unsuccessfully tried to reform the state’s HIV laws. In late 2020, however, a second legislative attempt was more successful, and passed through the legislature in 2021 before being signed into law in August.

The 2021 changes to the law removed specific reference to HIV in all relevant laws except the ‘prostitution’ offence, instead applying them to ‘serious infectious or communicable diseases’. Additionally, the ‘exposure’ offence now requires conduct which creates a ‘substantial risk of disease transmission’ as determined by medical evidence, and separates the offence into categories whereby ‘reckless exposure’ is a misdemeanour, ‘knowing exposure’ a class D felony, and actual transmission a class C felony. This significantly reduced penalties to up to one year, seven years’, and ten years’ imprisonment, respectively. The reform also removed the exclusion of condom use as a defence, and added a specific defence of disclosure.

These changes to the law are undoubtedly a step in the right direction, but do not go nearly far enough to reform Missouri’s laws in line with international standards. While the new requirement of a risk of transmission should considerably limit prosecutions, the law still permits criminalisation where there is no intention to transmit and where transmission does not occur. There is also no explicit defence for condom use or adherence to HIV treatment, though theoretically these cases should no longer be prosecutable that use of these means there is no ‘substantial risk of disease transmission’. The lowering of penalties is also a positive move, but significant felony sentences are still available. Furthermore, the ‘prostitution’ offence was unchanged, meaning that sex workers living with HIV can receive lengthy prison sentences for conduct which poses no risk of transmission. We are so far unaware of reported cases following the 2021 reform, so it is yet unclear what effect this change to the law is having on how cases are dealt with.

For a detailed analysis of HIV criminalisation in Missouri, as well as all other US states, see the Center for HIV Law and Policy report, HIV Criminalisation in the United States: a Sourcebook on State and Federal HIV Criminal Law and Practice.

Laws

Missouri Statutes § 191.677

Serious infectious or communicable diseases, prohibited acts, criminal penalties

1. For purposes of this section, the term “serious infectious or communicable disease” means a nonairborne disease spread from person to person that is fatal or causes disabling long-term consequences in the absence of lifelong treatment and management.

2. It shall be unlawful for any individual knowingly infected with a serious infectious or communicable disease to:

(1) Be or attempt to be a blood, blood products, organ, sperm, or tissue donor except as deemed necessary for medical research or as deemed medically appropriate by a licensed physician;

(2) Knowingly expose another person to such serious infectious or communicable disease through an activity that creates a substantial risk of disease transmission as determined by competent medical or epidemiological evidence; or

(3) Act in a reckless manner by exposing another person to such serious infectious or communicable disease through an activity that creates a substantial risk of disease transmission as determined by competent medical or epidemiological evidence.

3. (1) Violation of the provisions of subdivision (1) or (2) of subsection 2 of this section is a class D felony unless the victim contracts the serious infectious or communicable disease from the contact, in which case it is a class C felony.

(2) Violation of the provisions of subdivision (3) of subsection 2 of this section is a class A misdemeanor.

4. It is an affirmative defense to a charge under this section if the person exposed to the serious infectious or communicable disease knew that the infected person was infected with the serious infectious or communicable disease at the time of the exposure and consented to the exposure with such knowledge.

Missouri Statutes § 567.020

Prostitution — penalty — affirmative defense

1. A person commits the offense of prostitution if he or she engages in or offers or agrees to engage in sexual conduct with another person in return for something of value to be received by any person.

2. The offense of prostitution is a class B misdemeanor unless the person knew prior to performing the act of prostitution that he or she was infected with HIV in which case prostitution is a class B felony. The use of condoms is not a defense to this offense.

3. As used in this section, “HIV” means the human immunodeficiency virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

4. The judge may order a drug and alcohol abuse treatment program for any person found guilty of prostitution, either after trial or upon a plea of guilty, before sentencing. For the class B misdemeanor offense, upon the successful completion of such program by the defendant, the court may at its discretion allow the defendant to withdraw the plea of guilty or reverse the verdict and enter a judgment of not guilty. For the class B felony offense, the court shall not allow the defendant to withdraw the plea of guilty or reverse the verdict and enter a judgment of not guilty. The judge, however, has discretion to take into consideration successful completion of a drug or alcohol treatment program in determining the defendant’s sentence.

Missouri Statutes § 575.155

Endangering a corrections employee, offense of — definitions — violation, penalties

1. An offender or prisoner commits the offense of endangering a corrections employee, a visitor to a correctional center, county or city jail, or another offender or prisoner if he or she attempts to cause or knowingly causes such person to come into contact with blood, seminal fluid, urine, feces, or saliva.

2. For the purposes of this section, the following terms mean:

(…)

(4) “Serious infectious or communicable disease”, the same meaning given to the term in section 191.677.

3. The offense of endangering a corrections employee, a visitor to a correctional center, county or city jail, or another offender or prisoner is a class E felony unless the substance is unidentified in which case it is a class A misdemeanor. If an offender or prisoner is knowingly infected with a serious infectious or communicable disease and exposes another person to such serious infectious or communicable disease by committing the offense of endangering a corrections employee, a visitor to a correctional center, county or city jail, or another offender or prisoner and the nature of the exposure to the bodily fluid has been scientifically shown to be a means of transmission of the serious infectious or communicable disease, it is a class D felony.

Further resources

Not all laws used to prosecute people living with HIV in this state are included on this page. For a comprehensive overview and analysis of HIV-related criminal and similar laws and policies, visit The Center for HIV Law and Policy

An analysis of enforcement data from 1990 to 2019, published February 2020. Of the four states that the Williams Institute has analysed to date (Missouri, Georgia, Florida, and California), Missouri has the most enforcement of its HIV-specific laws. When using the most comparable data, Missouri has one arrest for an HIV crime for every 60 people living with HIV (PLHIV) currently living in the state, compared to one arrest for every 370 PLHIV currently living in Florida, and one arrest for every 2,000 PLHIV currently living in California.