Overview

Two sections of a nineteenth century general criminal law (the Offences Against the Person Act 1861) related to grievous bodily harm can be used to prosecute either ‘reckless’ (section 20) or ‘intentional’ (section 18) disease transmission in England. Prosecutorial guidance has established that transmission of some STIs, including HIV, amounts to grievous bodily harm. Importantly, as these offences relate to the causing of ‘grievous bodily harm’, proven transmission, and not merely ‘exposure’, is required.

The maximum penalty for reckless transmission is a prison sentence of five years for each person someone is found guilty of infecting. The maximum penalty for intentional transmission is life imprisonment. Non-UK residents can be recommended for deportation upon completion of their sentence.

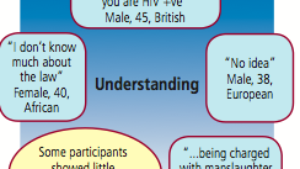

Several appeal court judgements, as well as regularly updated guidelines from the Crown Prosecution Service, have established that a person living with HIV can only be found guilty of HIV transmission if all of the below apply:

-

- They had sex with someone who didn’t know they had HIV (meaning that disclosure can be a defence).

- They knew they had HIV at that time (although not testing despite strong evidence they might have been infected, known as ‘wilful blindness’, is not a defence).

- They understood how HIV is transmitted and had sex anyway, or had sex with the intent to transmit HIV.

- They had sex without using ‘safeguards’, which can include either condoms or being on effective antiretroviral therapy.

- It can be proved beyond reasonable doubt that HIV was transmitted from the defendant to the complainant(s).

The latest update to the CPS guidance for England and Wales in March 2023 for the first time clearly endorsed the scientific consensus that having an undetectable viral load effectively eliminates the risk of HIV transmission (U=U), meaning that cases in which the accused’s viral load is undetectable should no longer be taken to court as the person could not be found to have been reckless about the risk of transmission.

Since the first successful prosecution in England, of Mohammed Dica in 2003, there have been around 30 known HIV criminalisation cases relating to sexual acts, almost all for reckless HIV transmission. The one successful prosecution for intentional transmission, in 2018, was exceptional, and was only possible because it was proven that the accused had both maliciously and intentionally tried to – and subsequently did – pass on HIV to a number of complainants.

Another case initiated in 2011 apparently involved an initial charge for intentional transmission, but subsequent reporting clarified that the man was charged with reckless transmission (section 20). The man was arrested for allegedly transmitting HIV to a partner after he failed to consistently take antiretroviral medication, but was released due to lack of evidence. He was then deported to Jamaica as it emerged he didn’t have the legal right to be in the UK. However, more than a decade later, new evidence was uncovered and the man was extradited back to the UK where he pled guilty to reckless transmission in March 2023. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment in April.

Despite these known cases, it is believed that many more individuals (possibly hundreds) have been arrested and investigated, according to a 2009 report, Policing Transmission, which reviewed police handling of criminal investigations relating to transmission of HIV in England and Wales, 2005-2008.

HIV has also informed use of the criminal law in other ways. In May 2020, a woman living with HIV and Hepatitis C, who also had mental health issues, was arrested for being drunk and disorderly. While at the police station she threw a soiled sanitary towel at a police officer. She was convicted of assaulting an emergency worker, with the judge giving her a 26 week jail sentence “to express public disgust”. Her HIV status was known because her file had already been ‘marked’. In June 2020, a man living with HIV who was also arrested for being drunk and disorderly was sentenced to 22 weeks in prison for assaulting two emergency service workers after he spat or attempted to spit on them four times. The offence was considered serious because it considered a deliberate attack on a public servant carrying out public duties at a time of national crisis (COVID-19). In October 2020, two women living with HIV were jailed for biting police officers in two separate incidents. In the first case, a woman living with HIV was jailed for more than two years after biting a police officer and injuring others. The second case involved a woman with an almost undetectable viral load jailed for 14 months although the bite did not break the skin.

While disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status before sex is not mandated under English law, courts have applied Sexual Offences Prevention Orders to a small number of individuals, requiring them to disclose their HIV-positive status before engaging in sex. In one case, a man was found liable for breaching a SOPO on numerous occasions resulting in several prison sentences, most recently for four years in December 2020. In another case in 2023, a man received a suspended prison sentence and was required to be GPS monitored for failing to abide by a Sexual Risk Order to disclose his HIV status to sexual partners.

In addition to HIV-related prosecutions, there have been also been successful prosecutions for the sexual transmission of herpes and for hepatitis B.

Laws

Offences Against The Person Act 1861

Section 18. Wounding with intent to do grievous bodily harm

Whosoever shall unlawfully and maliciously by any means whatsoever wound or cause any grievous bodily harm to any person …with intent, … to do some … grievous bodily harm to any person, [or with intent to resist or prevent the lawful apprehension or detainer of any person,] shall be guilty of an offence, and being convicted thereof shall be liable … to imprisonment for life.

Section 20. Inflicting bodily injury, with or without weapon

Whosoever shall unlawfully and maliciously wound or inflict any grievous bodily harm upon any other person, either with or without any weapon or instrument, shall be guilty of a misdemeanour, and being convicted thereof shall be liable … to imprisonment … for not more than five years.

Further resources

Information for individuals living with HIV about the law in England (and other UK jurisdictions).

Resources for both individuals living with HIV, as well as those advocating on their behalf, on all aspects of HIV criminalisation in England (and other UK jurisdictions).

Explores use of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 to prosecute people who have transmitted HIV infection to sexual partners in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Examines evidence in cases of sexual HIV transmission and considers the likely impact that criminalising HIV transmission has on public health, especially HIV prevention. Includes recommendations.

This internal guidance from the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) for England & Wales sets out how prosecutors should deal with cases where there is an allegation that the suspect/defendant has passed an infection to the complainant during the course of consensual sexual activity. It should be read in conjuction with the external CPS Policy for prosecuting cases involving the intentional or reckless sexual transmission of infection.

A review of police handling of criminal investigations relating to transmission of HIV in England and Wales, 2005-2008. The report was used as evidence to argue for both prosecutorial and police guidance. To get a sense of its findings and impact see also the aidsmap.com coverage of the launch of the report held in the UK House of Commons in January 2009.