Living With H.I.V. Isn’t a Crime. Why Is the United States Treating It Like One?

States’ nondisclosure statutes, used to persecute marginalized populations, discourage testing and treatment.

By Chris Beyrer and

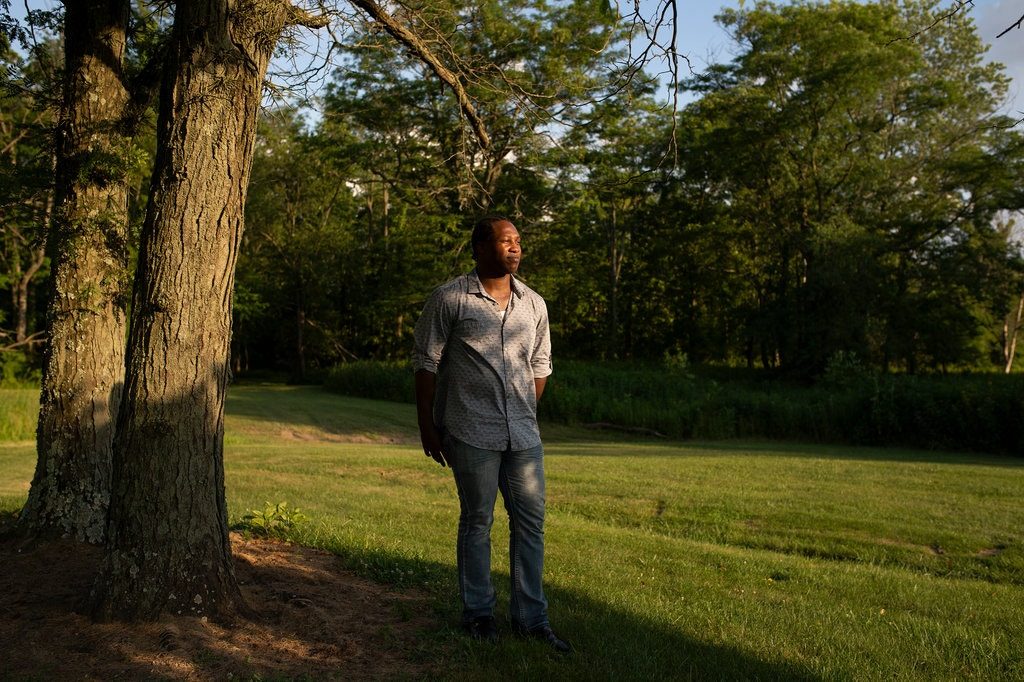

Dr. Beyrer is an infectious disease epidemiologist. Mr. Suttle was convicted under Louisiana’s H.I.V. criminalization statute.

Michael Johnson, a former college athlete convicted in 2015 of not disclosing his H.I.V.-positive status to sexual partners, was released on parole from a Missouri prison last month. Mr. Johnson, who is gay and black, had maintained his innocence, and there was no proof that he had transmitted the virus. And yet that didn’t seem to matter in the court of public opinion, or in the court of law.

On Dec. 20, 2016, a Missouri appeals court ruled that Mr. Johnson’s trial had been “fundamentally unfair.” H.I.V. nondisclosure is inherently difficult to prove yet seemingly easy to condemn, as shown time and again by judges and juries worldwide. Nowhere is this truer than in the United States, where people with H.I.V. are still being prosecuted under outdated or misapplied laws.

During the early years of the AIDS epidemic, an H.I.V. infection was tantamount to a death sentence. Through major advances in antiretroviral therapies, H.I.V. is now a manageable, chronic condition. A person whose infection is newly diagnosed can expect to live a near-normal life span, and most seropositive people will never progress to further AIDS-defining complications.

Today we also know much more about how difficult H.I.V. is to spread. When used correctly, condoms are highly effective means of prevention. Research has also shown that when people are treated with antiretroviral drugs so that their viral load cannot be detected by standard blood tests, the virus cannot be transmitted to sexual partners. This true of both heterosexual and male same-sex couples. Simply put, scientific evidence on actual harm and transmission does not support the singling out of people living with H.I.V. through the heavy hand of criminal law.

Mr. Johnson’s trial was rightly deemed unjust due to prosecutorial misconduct. But injustice remains deeply entrenched within the society that created the laws that criminalized his actions in the first place. At least 29 states, mostly in the Midwest and Deep South, have laws that make H.I.V. nondisclosure, exposure or transmission a crime.

These laws constitute one more layer of marginalization for those whom the criminal justice system already disproportionately prosecutes, convicts and harshly sentences: black people, trans women, migrants, people who sell sex, people who inject drugs and L.G.B.T.Q. youths. Such laws have not been shown to reduce H.I.V. transmission, but they do discourage those at risk from getting tested, which undermines public health rather than protects it.

The United States has the unfortunate distinction of being among the countries most aggressively prosecuting people living with H.I.V., after Russia and Belarus, according to a recent report by H.I.V. Justice Worldwide. In these places, people living with the virus could be just one disgruntled partner away from finding themselves in a courtroom.

In the United States there are thousands of cases where H.I.V.-specific charges were filed, or people faced heightened charges or punishments simply because they had the virus. We don’t know how many others have been threatened or blackmailed with criminal prosecution — the law becomes a weapon in abusive relationships — but those numbers are surely considerable. In almost all cases, this all-too-real risk is greater than any (highly unlikely) risk of actual H.I.V. transmission.

Prompted by concerns that the law was being applied contrary to scientific evidence, last summer a group of 20 H.I.V. scientists from around the world issued an expert consensus statement intended to assist experts involved in cases of alleged H.I.V. exposure, transmission or nondisclosure. They urged governments and people working in the justice system to ensure that the significant advances in H.I.V. science are taken into account in H.I.V.-related legal cases.

As the global scientific community continues to learn more about the disease and its transmission risks, lawmakers and criminal justice systems must similarly evolve their thinking to align with evidence, not fear. Scientists and clinical providers have obligations here, too. They should use their knowledge to support law reform efforts and provide expert testimony, using the consensus statement to educate and advocate change. No one should be forced to endure what Michael Johnson, and so many others living with H.I.V., have had to suffer.

Chris Beyrer is a professor in public health and human rights at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Robert Suttle is the assistant director of the Sero Project, which works to end unfair H.I.V.-related prosecutions.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.