Lawmakers in Nepal are considering a draft law that singles out people with HIV and hepatitis B, contrary to recommendations from UNAIDS and the Global Commission on HIV and the Law.

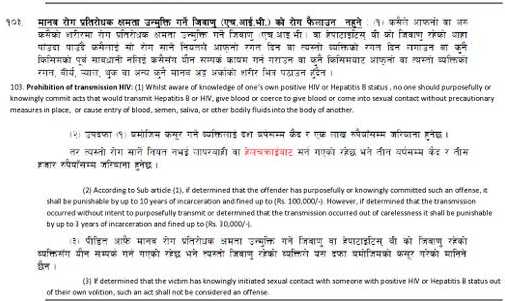

According to the draft text, tweeted by IRIN Humanitarian News reporter Kyle Knight, Article 103 ‘Prohibition of transmission HIV’ of Chapter 5, Offenses against Public Interest, Health, Safety, Facilities and Morals, criminalises people who are “aware of knowledge of one’s own positive HIV or Hepatitis B status”, who “purposefully or knowingly commit acts that would transmit Hepatitis B or HIV, give blood or coerce to give blood or come into sexual contact without precautionary measures in place, or cause entry of blood, semen, saliva, or other bodily fluids into the body of another.”

draft criminal code in #Nepal parliament appears to criminalize HIV transmission. pic.twitter.com/VXBlaWIzmV

— kyle g knight (@knightktm) November 2, 2014

There are two levels of mens rea (state of mind) for such acts.

If it is “determined that the offender has purposefully or knowingly committed such an offense” the penalty is “up to 10 years of incarceration” and a fine up to 100,000 Rupees (approx. US$1000).

“However, if determined that the transmission occurred without intent to purposefully transmit or determined that the transmission occurred out of carelessness it shall be punishable by up to 3 years of incarceration and” a 30,000 Rupee (approx. US$300) fine.”

If the complainant has “knowingly initiated sexual contact with someone with [a] positive HIV or Hepatitis B status out of their own volition, such an act shall not be considered an offense.”

Given that article 102, ‘Prohibition of transmission infectious diseases’ already criminalises anyone who should “commit acts that could endanger the lives of others through the transmission or the potential transmission of infectious diseases” it is unclear why people with and HIV and hepatitis B are singled out, unless it is to provide a consent defence, which is not allowed in article 102.

In addition, article 102 provides for three levels of mens rea: “purposefully or knowingly” (with a penalty of up to 10 years of incarceration and a Rs. 100,000 fine); “negligently or irresponsibly” (up to 5 years of incarceration and a Rs. 50,000 fine); and “carelessly or recklessly” (up to 3 years of incarceration and a Rs. 30,000 fine).

It is unclear how a court (or the police or prosecutors) would be able to differentiate between the various states of mind outlined in this draft law.

And whilst it could be seen as a positive step to allow for a consent defence, the law is far too vague and broad in terms of defining the acts that “would” risk HIV exposure or transmission, potentially criminalising all sex (including kissing and oral sex) by a person living with HIV unless their partner consented, even if no exposure was possible and/or no transmission is alleged to have occurred.

This would result in people living with HIV or hepatitis B being vulnerable to arrest and prosecution which would increase stigma and make it more likely that testing, treatment and beneficial disclosure would not take place.

HIV advocates in Nepal are currently responding to the draft law by sensitising parliamentarians to the notion that such laws do more harm than good to public health.